Interview by Mir Yarfitz

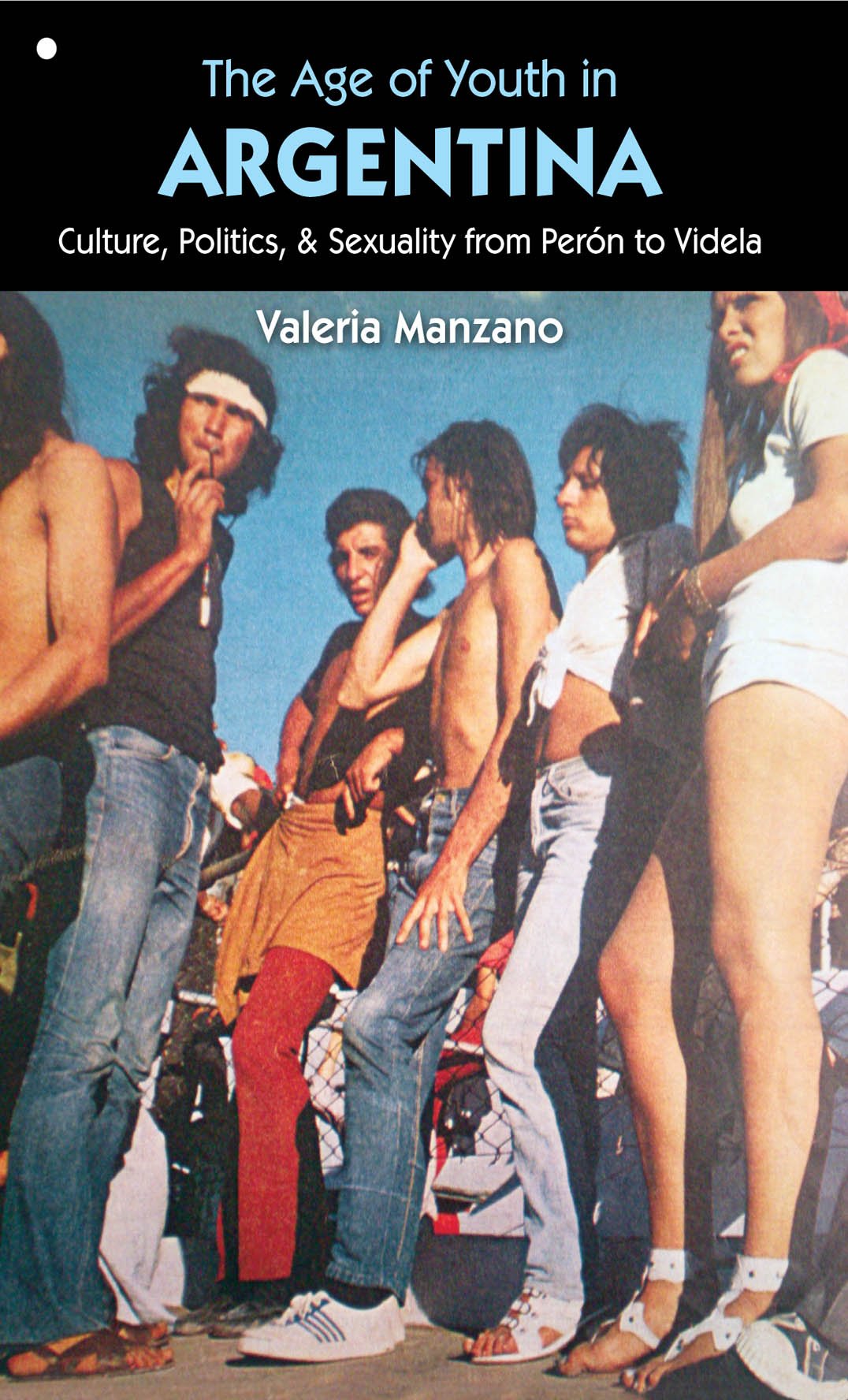

In the 1950s, “youth” became a new consumer category of central importance to the worldwide social, cultural, and political transformations of the following decades. In The Age of Youth in Argentina: Culture, Politics, and Sexuality from Perón to Videla (University of North Carolina Press, 2014), Valeria Manzano develops the first in-depth study of how young people in this South American nation asserted a new collective identity in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. Pushing back against the authoritarianism of parents, schools, and repressive governments, Argentine youth demanded self-determination in their sexual, educational, and social lives. As symbols of modern changes in gender roles and sexual practices, youth also served as a lightning rod for the dreams and anxieties of experts and rulers. Eroticism pervaded the home-grown Argentine rock music scene, and the new fashions of blue jeans and miniskirts allowed young men and women to redefine masculinity and femininity. Young people literally put their bodies on the line in their fight for sexual and other freedoms: some joined “Third World” violent resistance movements, embodied by the Argentine-born martyr, Ché Guevara. Additionally, in the brutal military dictatorship of 1976-1983, 70% of the “disappeared” were under thirty, eliminated as potential threats to the rigid social order.

Mir Yarfitz: Your book uses sexuality as one of a few analytical lenses to investigate the emergence and evolution of youth culture in Argentina between the 1950s and 1970s. Why did you decide to focus on sexuality, and what does that lens add to histories of Argentine culture and politics in that era?

Valeria Manzano: My decision to focus on sexuality was based upon two different, albeit related, sets of issues.

On the one hand, from the perspective of the “adult” voices that discussed youth in the public arena, youth and sexuality were closely interconnected terms. Virtually all the public conversation about youth in the 1950s and 1960s revolved around what was perceived as the new autonomy of young people vis-à-vis the adult world, and the conversation was saturated with references to the perils that this new autonomy posed to so-called traditional sexual mores. Psychologists, educators, “family-defense” groups, and the media insistently debated the apparent rise in premarital sex and the ways it changed gender relations and family life. Some saw the decline of the “taboo” of female virginity before marriage as both a modernization of sexual mores and the beginning of a more egalitarian paradigm of gender relations. Others, especially those associated with Catholic family-defense groups and some state-led initiatives, interpreted the relaxation of sexual mores and the acceptance of premarital sex as destabilizing an organized and hierarchical social order that was based on clear-cut gender roles and patriarchal values. Youth sexuality and the extension of premarital sex thus served as one crucial theme to discuss the dynamics of sociocultural modernization in the 1950s and 1960s.

On the other hand, from the perspectives of those who occupied the category of youth in the 1950s and 1960s, it was quite clear that something was indeed changing in terms of sexual mores and practices. The extension of premarital sex, especially among the middle classes, allowed me to investigate the connections between subjective individual changes and collective sociocultural experiences. More importantly, perhaps, it allowed me to analyze the gendered aspects of sociocultural modernization. I found that it was young women who more forcefully embodied and shaped sociocultural modernization. The cohorts of young women who came of age in the 1960s were the first ones to gradually voice their approval of premarital sex in the public arena, and they—like many young men—did so in the framework of a discourse connecting sex with love and responsibility. In many respects, the young women who came to occupy the category of youth in the 1970s built on the successes of these previous challenges to familial and sexual arrangements; they did not face as much familial or cultural concern about their “autonomy” and they grew up amidst the normalization of premarital sex in public culture. By the 1970s, a new understanding of sexuality had emerged among middle- and working-class youth—the disengagement of sexuality from marriage. To sum up, in the 1970s the actors and the very terms of discussion had dramatically changed vis-à-vis the 1950s. What was in between, in my view, was a set of profound transformations in sexual mores and practices that young people, especially young women, helped to shape.

In terms of what my work’s focus on sexuality adds to our understanding of Argentina’s history, I claim that those transformations are crucial for understanding the dynamics of sociocultural modernization, including its possibilities and limits. I truly believe that culture, politics, and sexuality transformed together. In this respect, then, a history of youth—doubtless some of the most significant actors of the era—afforded me the opportunity to connect and discuss previously known processes with transformations in the realms of gender and sexuality. For example, it was through the discussion and interventions in the arena of youth sexuality that a new “conservative bloc”—which had political and cultural ramifications—emerged throughout the 1960s and helped to create consensus for the imposition of Argentina’s last, and most dramatic, military dictatorship in 1976.

MY: To what extent was the category of youth defined by consumerism? How did the sexualization of youth by mass media differ from the ways youth expressed their own sexuality? For example, what was the difference between the way that youth sexuality was deployed in ads for blue jeans and the range of meanings youth themselves ascribed to the garment?

VM: The significance of market-oriented actors in defining what youth meant was indeed crucial in that era, both in Argentina and transnationally. The very notions of “rebellion” and “contestation” were articulated and disseminated through market-oriented forces, and both were crucial to defining youth as a category in the 1960s. It is difficult to underestimate the roles of music producers, advertisers, and even textile factory owners in defining the parameters of how young people were supposed to behave, think, and feel. However, I tried to explain that by no means were market-oriented actors the only ones to define those parameters. They were not the only “adult” actors shaping the meaning of “youth.” Educators, psychologists, journalists, and politicians were sometimes just as significant. Moreover, young people appropriated market-made products in myriad ways, and not always how market-oriented actors wanted them to.

The example of blue jeans shows the relationships between market-oriented actors and youth. While ads for blue jeans included erotic displays and the denim items themselves were increasingly tight, young people used blue jeans in different ways. Many young women and men did use them to more confidently display their bodies, a usage in line with the eroticization of public culture that advertisements and producers suggested. However, as time went by, other uses—and debates—appeared as well, including the apparent “unisex” fashion that jeans encoded and that tended to blur clear-cut gender divides. Through their own choices in terms of make-up and hair styles, young women and men displayed their bodies, sexualizing them through the appropriation of market-made elements.

MY: You write, “Talking about sex meant talking about youth, and vice versa.” Did older people in this period also start using the pill, engaging in more or different extramarital sex, or getting divorced more often? Does Argentina have the same devaluation that we do in the US of older people as sexual beings?

VM: There is evidence that in the 1960s there were novelties in older people’s sexuality, as well. As the historian Karina Felitti has shown, for example, the early history of the Pill in Argentina (in the early 1960s) was connected with the efforts of a group of Catholic gynecologists to prevent abortion among working-class, married women. That history has been made invisible by the popular association of the Pill with young women. In addition, numerous popular movies touched upon the expansion of per-hour hotels in the main cities, suggesting that extra marital sex extended to older couples. In terms of divorce, Argentina did not have a divorce law until 1986. However, it did not mean that married older couples did not get separated—there were informal ways of doing so and, for the upper classes, there was the possibility of getting formal divorce by going abroad. As historian Isabella Cosse has shown, those practices spread in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Regarding the question about the devaluation of older people as sexual beings in Argentina, I do assume that it is quite similar to the US. In fact, the strong association of sexuality with youth that took place in the 1960s in some ways involved a reinforcement of that devaluation. Youthful bodies, eroticism, and sex practices set the standards of beauty and desirability, a dynamic that may have been “liberating” for young people but was likely exclusionary for older Argentinians.

MY: Police and some sectors of the public responded aggressively to the emergence of new forms of masculinity, including rock culture. To what extent did these subcultures in turn try to distance themselves from homosexuality and effeminacy? You suggest that the rock and hippie scenes might have imagined more egalitarian possibilities than did the armed left. Why weren’t the radical left’s New Men, such as the guerrillas who admired Ché and Castro, more invested in changing women’s roles and relations between the sexes?

VM: In my research I found that, until the mid 1970s, rock culture in Argentina constituted a homosocial space. Rockers (musicians, poets, producers, fans) were mostly young men, who created what I called “a fraternity of long-haired boys.” In some ways, the homophobic reactions that the fraternity incited in the public arena helped to explain the abundant display of rockers’ machismo—in lyrics, in the ways competing bands referred to each other at times of aesthetic confrontations, and in the efforts of many rockers to separate themselves from effeminacy. It is worth noting, however, that at least some trends within rock culture were as “tolerant” of homosexuality as it was possible to be at the time amidst heterosexual young people. As I have shown in other work, in the realm of one of the most active independent rock labels (named Mandioca), Moris, one of the pioneers of rock music in Argentina, recorded in 1970 a song titled “Escúchame entre el ruido” (“Hear me between [amidst] the noise”), which is to my knowledge the most acute critique of heteronormativity that rockers ever created in the country.

I do suggest that rock-related countercultures, such as the hippies, imagined and, to some extent, enacted more egalitarian relations between women and men. Some of their members advocated for a total struggle against “the system,” including the basis of patriarchy—something that wasn’t in the agenda of revolutionary movements at the time. That project was apparent, for example, among those involved in communal life. In communes they imagined new childrearing practices whereby young men’s involvement was at odds with more mainstream practices. In contrast, the political sub-set of the large youth culture of contestation of the early 1970s did not have an agenda in which changing of the relations between the sexes figured prominently. Their focus was on struggling for socio-political change, and many believed that this sort of social emancipation—which included the end of private property—would pave the way for a truly egalitarian future society, whereby sexual and gender equality could be achieved. Also, many involved with the political New Left understood that putting sexual and gender issues on the agenda implied diverting energies from the more pressing needs of political struggle. This was evident, for example, in the debates that young women who were part of the Marxist or Peronist movements had with their feminist counterparts. Although some young female militants rhetorically agreed that women’s emancipation required specific struggle and strategies, they were keen to postpone the discussion on that struggle so as to prevent further tensions within the revolutionary movements.

MY: I’m also impressed with your efforts to chart the complicated evolution of various strands of Peronism. I often struggle to explain to my students how Peronism doesn’t map neatly onto the categories of right and left with which they are more familiar. Do you think gender and sexual politics tied to this ideology differed substantially from those of the socialist left or more economically conservative right?

VM: I begin by pointing out that I don’t think of Peronism as an ideology but as a national-popular movement, which at different junctures involved different ideological strands. That said, my focus was on both revolutionary Peronism and right-wing Peronism in the early 1970s.

I think that the youth involved with revolutionary Peronism shared with their socialist counterparts new sensibilities about sexuality that were becoming mainstream in Argentina’s public culture at large. They dissociated sexuality from marriage, while also maintaining confidence that stable and monogamous heterosexual partnerships were the antidote against “liberalism” and the best possible venue for organizing their families. Within those revolutionary organizations, these beliefs were guiding forces for both individual behaviors and collective discipline, and in many circumstances, occasional “affairs” and homosexuality were severely punished (for example, by downgrading the “suspects” on organizational ladders or by expelling them from revolutionary organizations). At least in the youth movements within Peronism, then, there was nothing truly distinctive in comparison to their peers in other youth political movements of the era. Moreover, both Peronists and socialists were ideologically opposed to the spread of the Pill, which they understood to be an “imperialist tool” for controlling the populations in the Third World. Of course, this does not mean that young women in those movements accepted the idea as such, and many went on the Pill anyway.

As for the conservative right, which also included several strands of Peronism, differences were more substantive. In 1974, for example, the then president, Juan Perón, issued a decree to prevent contraception from being publicized in public hospitals and to restrict the sale of the Pill. Although the overt justification for such a decision was that to become a world-leading nation, Argentina had to increase its population, the decree was part of a broader attack on the sexual transformations that Argentines had undergone during the 1960s, which had included the redefinition of legitimate heterosexual sex. As the 1970s went on, the “conservative block”—which included Peronists—became ever more defensive of a patriarchal and “family-oriented” social order, and even rhetorically they did not advocate for sexual and gender equality. As became apparent after the 1976 coup, the conservative right sought to restore the principles of authority in social life and cut short all the cultural and sexual transformations that youth embodied.

MY: I find your comparisons to other countries intriguing. Could you recap the ways sex and youth culture in Argentina were either unique or in line with certain transnational patterns? Were there some ways that Argentina looked more Latin American, and in other ways more European?

VM: Argentina is one “case” within the larger panorama of the cultural and political ascendancy of youth in the mid-twentieth century. I do think that there were several transnational patterns at work, including economic changes in the postwar period that afforded families the chance of having their children stay in the educational system for longer, an acceleration of communications, the market-oriented production of youth-related goods, and the cultural and ideological valorization of the “new” over the traditional in all spheres of social life. Those patterns explain the simultaneity of the ascendancy of youth to the center stage of cultural and political phenomena across national divides. When it comes to sexuality, the “normalization” of premarital sex in the 1960s occurred transnationally, even as it was debated in different terms at local levels. My research shows that those terms in Argentina—as in other Latin American countries, such as Mexico—were largely those of the debates over “modernization.” In addition, in contrast with North Atlantic countries, prominent gay and feminist groups did not emerge in Argentina or in most Latin American countries in the 1960s and 1970s. It doesn’t mean that there were no gay and feminist groups, but they were marginal in defining the place and meanings of sexuality and gender in public culture. This, in turn, relates to what I think was rather unique in Argentina, namely, the ways in which the properly political sub-set of youth contestation—basically, revolutionary movements—came to dominate the entire youth culture and the meanings of youth in the political and cultural arena.

Valeria Manzano is an associate researcher at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina, and Associate Professor of History at the Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales, where she coordinates the Research Program on “Recent History.” She holds a PhD in Modern Latin American History from Indiana University (2009) and has been an Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Chicago (2010-12). She is the author of The Age of Youth in Argentina: Culture, Politics, and Sexuality from Perón to Videla (The University of North Carolina Press, 2014) as well as a dozen of articles on youth, politics, and sexuality published in Hispanic American Historical Review, Journal of Latin American Studies, and Journal of Social History, among others.

Mir Yarfitz is an Assistant Professor of History at Wake Forest University. He is currently completing a book manuscript about immigrant Ashkenazi Jews in organized prostitution in Buenos Aires between the 1890s and 1930s as part of broader transnational flows of sex work migrants and related debates about race, morality, and marriage. His other main project addresses gender-bending in early twentieth century Argentina, analyzing transgenderism “before the word” as concepts of homosexuality and transsexuality unevenly travelled the world.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com