There’s a long history to the intersection of religious faith and sexuality in Scotland. The introduction of same-sex marriage, LGBT clergy, and the Church of Scotland’s liberalising attitude to LGBT+ rights and issues all attest to significant changes within the institution. While the Church of England played a crucial role in the establishment of the Wolfenden Committee in 1954, which sat to examine the legal position regarding homosexual offences and prostitution, the Church of Scotland, by contrast, appeared remarkably reluctant to engage with any measure of homosexual law reform. Indeed, the church feared that the recommendation of the 1957 Wolfenden Report to decriminalise consensual sex between male adults would ‘lead to further and greater depravities’ (‘Church and Nation’, Glasgow Herald, 7 May 1958, p. 6). The Church of Scotland maintained this line for over a decade, albeit softening its stance slightly by the end of the 1960s, at which time it viewed homosexuals as suffering from a pitiful handicap (Church of Scotland, Assembly Report, 1967). I’ve written elsewhere about how the church’s public disavowal of homosexual law reform impacted upon religious queers in Scotland, but there is another story to tell, one which positions both the protestant Church of Scotland and the Scottish Roman Catholic Church centrally in the development of the homosexual law reform movement in Scotland.

From its inception in 1969, the Scottish Minorities Group (SMG) – Scotland’s foremost homosexual law reform organisation – saw amicable relations with Scottish churches as imperative to a productive campaign to bring the law in Scotland in line with England and Wales, where limited decriminalisation had occurred in 1967. To this end, the SMG actively sought support from church representatives sympathetic to its objectives, and this appeal was enthusiastically accepted by the Reverend Simpson, a representative of the Church of Scotland’s Moral Welfare Committee. Simpson was optimistic that the church’s attitude towards law reform was in the process of changing and he encouraged Scottish homosexuals to be discriminating but ‘wholehearted about [their] homosexual proclivities’. The church, with assistance from the ecumenical Christian Iona Community facilitated the SMG’s organising efforts by permitting the group to meet in church properties. The group’s founder, Ian Dunn, later remarked that without the support of the Church of Scotland, the Scottish law reform movement would have been much slower and more hesitant. Another founding member of the SMG, ‘Walter’, told me that, ‘the church[es] deserve a lot of credit for being the only arm[s] of [Scottish] society which facilitated reform’ during the 1970s.

Yet, this relationship was to falter. This was not from a change in attitude from either side, but related instead to personality clashes and competing priorities. In addition to its reform objectives, the SMG pursued a social agenda, sponsoring licensed discos and other activities perceived as non-religious. Simpson was concerned that the SMG would minimise the pastoral and spiritual role of his church within the group. The breakdown in this relationship led to the group being ‘evicted’ from church premises in late 1970.

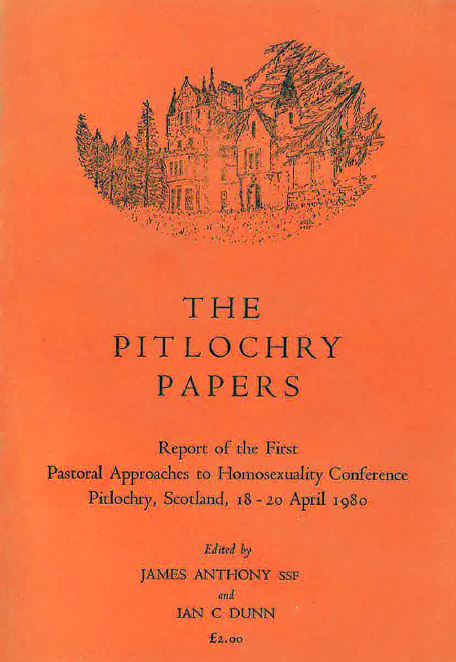

The SMG found an unlikely saviour in the Scottish Roman Catholic Church, which provided new premises, thereby saving the organisation from folding during the early 1970s. The relationship between the two organisations was not limited to the provision of premises however. Notable clergy, including Anthony Ross (later to become rector at the University of Edinburgh) and Columba Ryan (the Catholic chaplain to the University of Strathclyde), played important roles in forwarding homosexual law reform, with Ross becoming an SMG vice president in 1971. At the first Pastoral Approaches to Homosexuality conference held in 1980, and co-organised by the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group (SMG morphed into the SHRG in 1978), Ross claimed to have counselled Scottish homosexuals on the importance of monogamy within same-sex relationships. Further, Ross viewed religious prohibitions on pre-marital sex as unhelpful for both heterosexuals and homosexuals (The Pitlochry Papers, 1980). Ryan played a part in the setting up of a homophile student group at Strathclyde in 1971.

The relationship between the homosexual law reform movement and the Catholic Church in Scotland was not a superficial one; Catholic priests were not infrequent speakers at SMG/SHRG events and meetings throughout the 1970s. At an open day for the Paisley branch of the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group the Catholic Marriage Advisory Service was in attendance, having its own stall. The emergence of the organisation Quest, for LGBT Catholics in 1973, pointed towards LGBT men and women of faith who felt confident enough in both their religious identities and sexual identities to organise and meet throughout Great Britain. The formation of a Scottish branch of Quest was undoubtedly assisted by the supportive relationships established between the SMG and representatives of the Catholic Church.

Despite the deterioration of the relationship between the SMG and the Church of Scotland, SMG members were grateful for the moral, spiritual and substantive support that both churches offered. This support came at a critical time in the movement’s emergence and represents an almost forgotten chapter in religious institutional support for sexual minority rights. The relationship between the SMG/SHRG and the Roman Catholic Church would itself eventually falter as well by the mid-1980s when a much stronger condemnatory rhetoric regarding homosexuality emerged from the Vatican, first through the 1976 declaration on ‘sexual ethics’, and later with Cardinal Ratzinger’s 1986 letter to bishops, which laid out the ‘official’ Catholic attitude to homosexuality. These documents informed much of the Catholic debate concerning homosexuality in Europe for the next 30 years. This was evident in Scotland from Cardinal Thomas Winning’s description of homosexual sex as ‘perverted’ in 2000, and extending to Peter Kearney’s more recent suggestion that the homosexual lifestyle leads to a premature death.

The interactions between religion and sexuality have been, to various degrees, central to recent debates about equal marriage. In Ireland, for example, positions on either side of the debate have been conceptualised both as religion ‘bashing’ and as representing a new chapter in social liberty. Underpinning many of the religious oppositions to equal marriage has been the suggestion that same-sex relationships are not conducive to religious faith and adherence. Yet, such a position fails to acknowledge that historically the neat binaries of ‘pro-gay’ and ‘anti-gay’ have been much more complex and nuanced, and that the history of progressive religious discourses on homosexuality has much deeper roots than some religious conservatives are willing to admit. This is particularly evident within the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland where liberal religious support for homosexuals pre-dates much more restrictive rhetoric.

Further reading:

Jeffrey Meek, ‘Scottish Churches, Morality and Homosexual Law Reform, 1957–1980’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 66 (2015), pp. 595-613.

Jeffrey Meek, Queer Voices in Post-War Scotland: Male Homosexuality, Religion and Society (Palgrave, 2015).

Jeffrey Meek is a research fellow at the University of Glasgow on the AHRC-funded ‘A history of working-class marriage in Scotland’. He maintains an active interest in the history of same-sex desire and manages the Queer Scotland website. His current research interests include same-sex unions in historical context, the emergence of queer subcultures in late 19th and early 20th-century Scotland, the interactions between religion and sexuality, and the medico-social history of HIV and AIDS in Scotland. Jeff’s book, Queer Voices in Post-War Scotland: Male Homosexuality, Religion and Society was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2015, and he has published on the input of religious organisations to the homosexual law reform movement in Scotland. He tweets from @DrJeffMeek.

Jeffrey Meek is a research fellow at the University of Glasgow on the AHRC-funded ‘A history of working-class marriage in Scotland’. He maintains an active interest in the history of same-sex desire and manages the Queer Scotland website. His current research interests include same-sex unions in historical context, the emergence of queer subcultures in late 19th and early 20th-century Scotland, the interactions between religion and sexuality, and the medico-social history of HIV and AIDS in Scotland. Jeff’s book, Queer Voices in Post-War Scotland: Male Homosexuality, Religion and Society was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2015, and he has published on the input of religious organisations to the homosexual law reform movement in Scotland. He tweets from @DrJeffMeek.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I’m currently reading AMIABLE WARRIORS, volume one (two more to follow) of Peter Scott-Presland’s meticulously researched history of CHE, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, who did (still do) so much to provide support and solidarity for the LGBT community as well as lobbying parliament(s) for incremental improvements to the community’s legal security. Strongly recommended.