In the postwar United States, the state’s project of preserving the family farm was yoked to its project of making the modern American family.

The family farm enjoys an uncanny amount of deference in modern American political culture in part because it is an unusually potent sexual symbol: it conveys a vision of permanent, healthy, and sustainable rural reproduction that is attractive to people from across the political spectrum. Agribusinesses, corn-and-soy farmers, conservatives, and farm state politicians deploy the term “family farm” whenever anyone has the chutzpa, say, to argue that child labor in agriculture should be vigorously regulated. But many environmentalists, foodies, locavores, and leftist politicians also tend to exempt family farms from criticisms of industrial agriculture.

If they can agree on nothing else, conventional agriculture and its critics agree on this: family farms are heroic—worthy of protection and celebration. And the key to the family farm’s magnetism is not the farm part but the family part. This deference indexes the degree to which the political economy of agribusiness has been fundamentally interwoven with definitions of “normal” intimacy, family, and sexuality.

It’s useful to examine the term “family farm” in relationship to both agricultural practice and cultural definitions of normal intimacy, sexuality, and families. If we want to think of the “family farm” as a description of a particular kind of enterprise, it doesn’t mean very much. The United States Department of Agriculture classifies 96.4% of all US farms as “family farms.” This classification spans tiny hobby farms to highly mechanized ones that sprawl across thousands of acres and employ hundreds of wage laborers. It’s impossible to tell what’s what from the term “family farm” alone, which is precisely why so many varied interests—and farms—can huddle under the protective umbrella of family farm rhetoric.

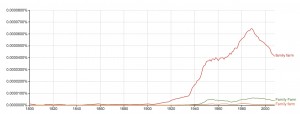

The celebratory use of the term “family farm” is a recent phenomenon in United States history. Nineteenth century Americans used the term “family farm” to describe a landed estate owned but seldom operated by a single, wealthy family. In most cases, these “family farms” were either hobby farms, or they were operated by hired managers and worked by slaves and wage-laborers. At the turn of the twentieth century, sociologists, agriculturalists, and reformers studying homesteaders in the Near West defined the term narrowly as a farm that was small enough that one family with only minimal supplements of wage-labor could operate it, though they did not always specify that the family should own the farm. These scholars usually assumed that the families in question would consist of a man, a woman, and their children, though they allowed that some “family-sized” farms might also include the parents and siblings of the farm’s ostensibly male operator.

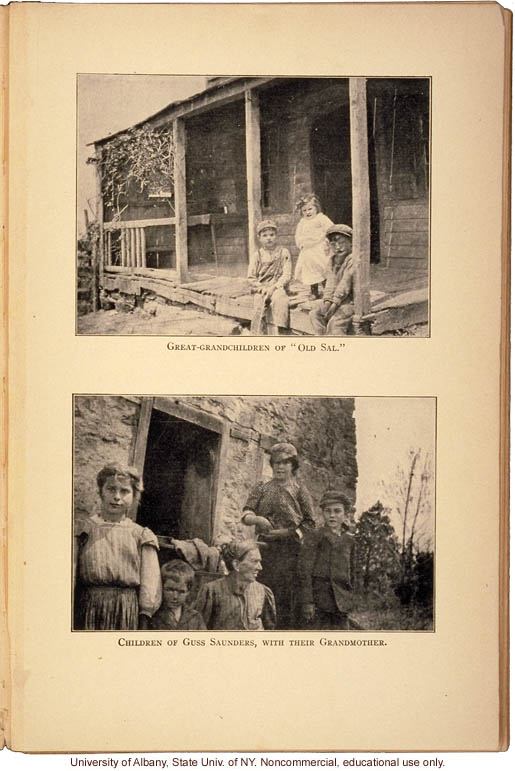

Rural sociologists rarely used “family farm” in a celebratory manner because they, along with most national commentators, often saw country families as degraded, vice-ridden, incestuous, and immoral. To be sure, these depictions reflected class and racial condescension. But such depictions were also reactions to the mobile and fragile existences of working-class family life in late nineteenth century America. The dispossession of indigenous populations, the resettlement of millions of acres of their land, the reconsolidation of Southern plantation agriculture through tenancy and share-cropping, and the movement of laborers from East Asia and Central America on to Western farms up-rooted communities, families, and individuals and dispersed them across America’s burgeoning agricultural empire. In short, these processes did little to stabilize American family life along the conventional lines that we now call a nuclear family.

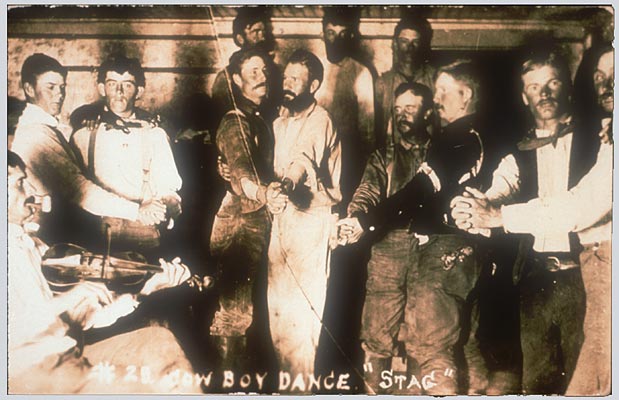

Rural people, often living in prolonged isolation and grueling deprivation, used events such as fairs, festivals, and barn raisings as rare opportunities to drink, dance, and fuck. These laborers rarely conformed to emerging middle-class sexual norms. Sex at the agricultural margins often involved transgressing class and racial boundaries. It also involved temporary sexual relationships, bigamy and polygamy, sexual commerce and barter, same-sex eroticism and gender-fluidity, and sex in semi-public spaces such as taverns, brothels, rented rooms, bunk houses, camps, and shared lodging.

Reformers often worried that rural people were oversexed. Rural children, after all, witnessed animal sex in barnyards from an early age, and some commenters wondered if this exposure didn’t awaken sexual impulses too early. Sprawling rural families and high birth rates signaled a bawdy underbelly of unfettered sexuality. The prominent sociologist Edward A. Ross, for example, memorably quoted one rural informant who scoffed at the supposed “purity of the open country . . . . The moral conditions among our country boys and girls are worse than in the lowest tenement house in New York.” On long and lonely winter nights, the informant continued, boys would “get together in the barn and while away the long winter evenings talking obscenity, telling filthy stories, recounting sex exploits, encouraging one another in vileness, perhaps indulging in unnatural practices.” Like many other rural reformers, Ross argued that rural family life needed to be better governed, rural people needed to be better educated about reproduction, and, more than anything, the “unfit” rural poor should be prevented from reproducing.

Following Ross’s line of thought, reformers argued for the restructuring of farms along lines that would standardize rural families and, in the process, make rural reproduction healthier and more predictable. Emerging in the decade after the First World War, reformers and the rural press called for a new gendered division of labor in which a male owner-operator “farmer” contributed all of the necessary revenue-generating labor, save a few “chores” reserved for his children, while the “farmer’s wife” concentrated exclusively on educating and caring for children. With women concentrating on “mothering” rather than working fields, reformers believed that rural children would be healthier, more attractive, more (respectively) masculine and feminine, and more likely to stay on farms as adults. The social reality never remotely resembled this ideal, but this hardly prevented the press, rural reform organizations, and the USDA from actively circulating it.

Against this backdrop, the ideal of the “family farm” rocketed to prominence. By the late 1930s, what had previously been an object of fear and loathing, emerged as a site of purity and wholesomeness. A family farm now implied a gendered division of labor and healthy reproduction. The family farm embodied this heterosexual ideal at a moment when pervasive white fears about a declining “American” population —that is, concerns that native-born whites were being “out-bred” by Southern and Eastern European immigrants and African Americans—were on the rise. These concerns and a desire to bolster white heterosexual family life motivated the government subsidy of family farms through New Deal-era modernization programs for (white) owner-operated “family farms.”

In the postwar period, this racialized and non-industrial image of the family farm continued to anchor agricultural policy discussions. The addition of the word family to the economic unit of the farm purified, rehabilitated, and even immunized the farming industry, which had indeed become an industrial scale endeavor, and which journalists and activists increasingly scrutinized for its harmful effects on collective health. If industry was unhealthy, ecologically corrosive, and unsustainable, many people assumed the rural family to be healthy, permanent, and reproducible. And, yet, in the same breath, these descriptions also revealed that the rural family life required a number of proactive policy mechanisms to survive—that, this supposedly healthy and natural form of rural reproduction depended upon the vigilant management of the modern nation-state.

The behemoth of the American state placed heterosexual family life at the center of national policy, by, for example, excluding soldiers discharged for “homosexual acts or tendencies” from the G. I. Bill and firing suspected “sexual deviants” from federal employ. Individuals who fell beyond the boundaries of normal sexuality—from sexual minorities to single mothers—risked direct state violence, in the form of police action and sterilization, as well as the slow violence of exclusion from the state benefits that formed the basis for postwar middle-class prosperity, like access to subsidized mortgages and fair employment. Parallel processes operated through the rural ideal of normal family life, as well: policies designed to defend “family farms” directed subsidies to farmers who already owned land, prevented estate taxes that disrupted generational transfers of wealth, excluded farmers who didn’t fit the racial and gendered contours of the family farm ideal, and forestalled legal protection for agricultural laborers.

The “family farm” as a celebratory signifier of white, rural heterosexuality, performs several interrelated functions. The seemingly timeless rural idyll lacquers recent and fragile sexual and economic arrangements with a false sense of permanence. This mythology does no justice to that past, and, worse still, it actively obscures the continuing violence industrial agriculture does to laborers and rural communities. The “family farm” literally naturalizes social hierarchies and landscapes that are, in fact, a product of sustained state violence and capitalist exploitation. But the family farm is also the ideal of those very reformers and bureaucrats who dreamed of reconstructing rural family life in accords with their own visions of gendered and sexual order. The family farm is how the state “sees” rural family life: it is the stable, predictable, and standardized unit built around the farmer and his wife who own and work land that will be inherited by their children. That it conceives of rural family life as exclusively heterosexual is obvious. And that the actual political economy of agriculture favors scale, capital-intensivity, and consolidation that is largely incompatible with single-family operation is beside the point. The rareness of such farms is, in some senses, the very root of its cultural power: a heteronormative ideal we constantly grasp for but can never quite reach.

Today, the fetishization of the family farm is inflected by long and sordid histories of state-sanctioned violence and discrimination around race, class, gender, and sexuality in rural America. Confronting such realities may be less immediately palatable than waxing romantic about an heirloom tomato, but they might be far more fulfilling.

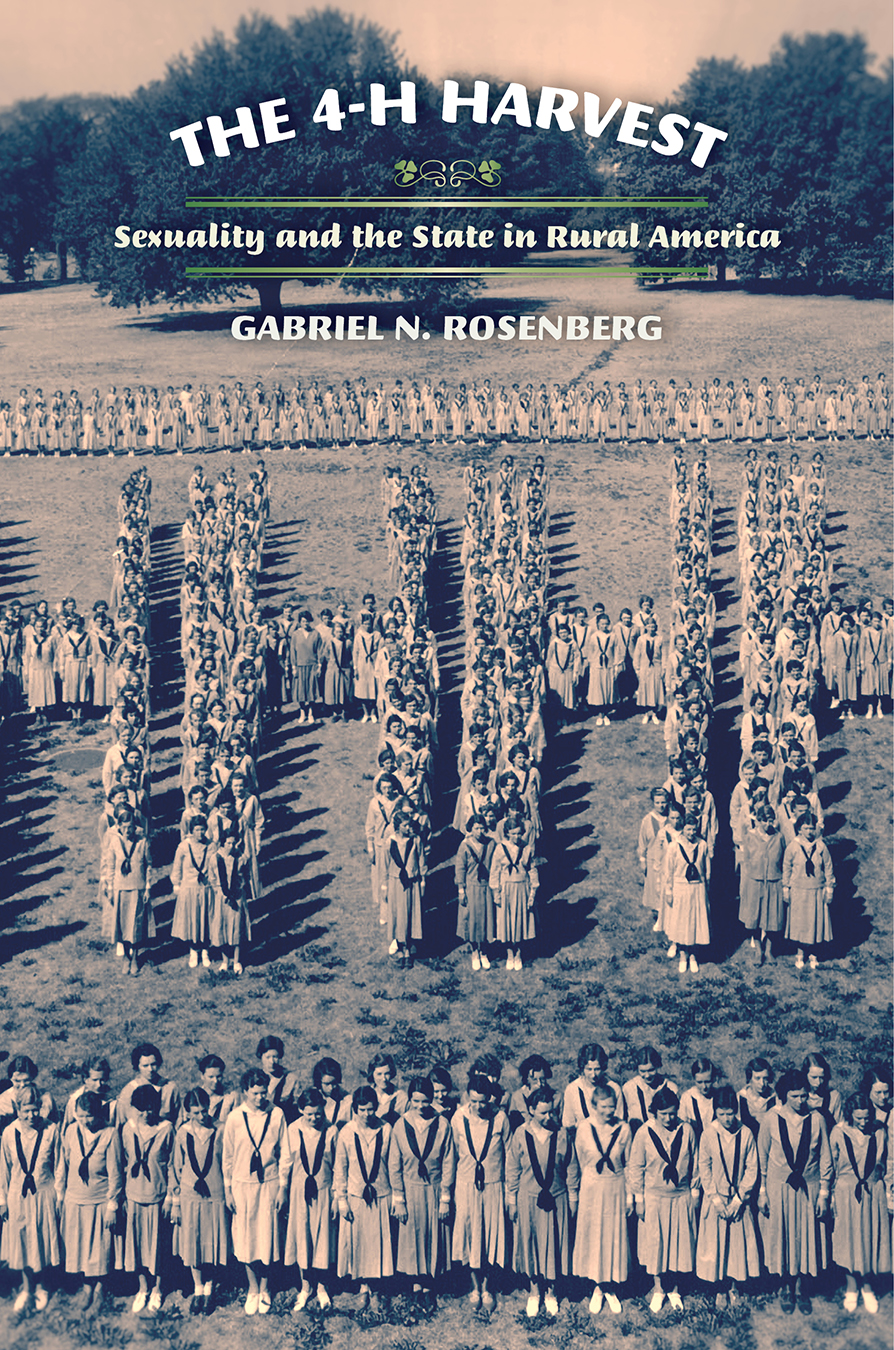

Gabriel N. Rosenberg is an Assistant Professor of Women’s Studies at Duke University. His research investigates the historical and contemporary linkages among gender, sexuality, race, and the global food system. His first book, The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), is a gendered and sexual history of the USDA’s iconic 4-H youth clubs. His latest article, “A Race Suicide among the Hogs: The Biopolitics of Pork in the United States, 1865-1930,” appears in the March issue of American Quarterly. Gabriel tweets from @gnrosenberg.

Gabriel N. Rosenberg is an Assistant Professor of Women’s Studies at Duke University. His research investigates the historical and contemporary linkages among gender, sexuality, race, and the global food system. His first book, The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), is a gendered and sexual history of the USDA’s iconic 4-H youth clubs. His latest article, “A Race Suicide among the Hogs: The Biopolitics of Pork in the United States, 1865-1930,” appears in the March issue of American Quarterly. Gabriel tweets from @gnrosenberg.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great article! I wonder what role the “Little House” books played in this process?