In 1934 Jamaica was gripped by a moral panic. According to a well-publicized British naval report, the island was “rife” with venereal diseases, particularly syphilis. Some venereal disease experts speculated that infection rates topped eighty percent of the population and included children as young as eight. The root cause of this epidemic was clear to the report’s author, one Colonel Stevenson, who noted “the almost complete absence of morals existing among a large class of Jamaicans.” Faced by “nightly swarms of prostitutes,” British sailors and tourists visiting the island, he argued, were endangered by the “female descendent of the slave days.” These conclusions threatened the island’s status as an important naval base for the British Empire and as a burgeoning tourist destination.

This report greatly exaggerated the prevalence of syphilis and had profound effects on public policy. Following the Stevenson report, venereal disease became the focus of public health in Jamaica for almost a decade. The purported prevalence of syphilis raised alarms in the upper and middle classes about the diseased bodies and immorality of the Afro-Jamaican masses. Calls for a campaign against venereal disease drowned out competing voices pleading for further investment in public health infrastructure and diverted scarce public health resources.

The rhetoric surrounding venereal disease in Jamaica offers a unique opportunity to examine racialized discourses of sexuality and disease that were frequently hidden beneath the surface and disguised as class bias or paternalistic concern within a Jamaican society that purported to be tolerant of racial difference. With its focus on the black female as a source of disease, 1930s Jamaica reveals deeply held beliefs about black sexuality, disease, and gender.

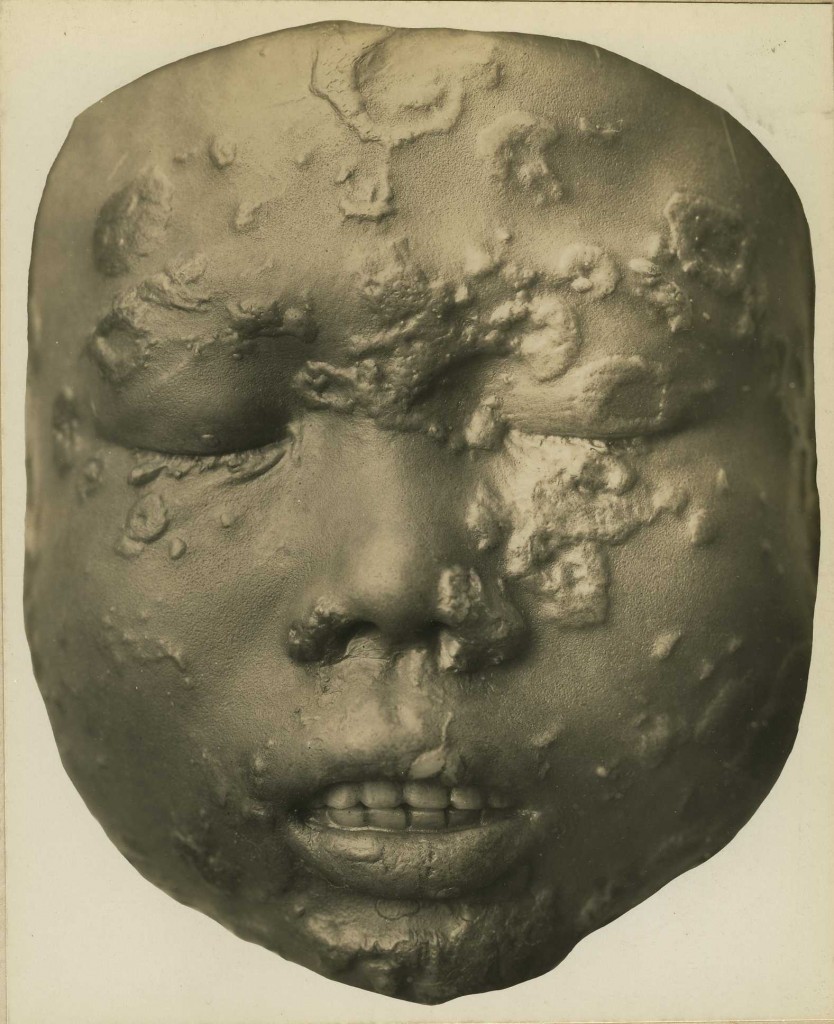

Moral panics can be defined as a moment when parts of a society believe that a minimal or non-existent social problem constitutes a grave or overwhelming threat. The moral panic over syphilis in Jamaica between 1934 and 1942 saw authorities including the military, upper-class reform organizations and the highest levels of the Jamaican colonial government dismiss the scientific evidence produced by members of the Island Medical Service and the popular and respected Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Division. These organizations presented unequivocal evidence that the Afro-Jamaican population was not overwhelmed with syphilis, but yaws, a non-venereal cousin that resulted from poverty and a lack of sanitation.

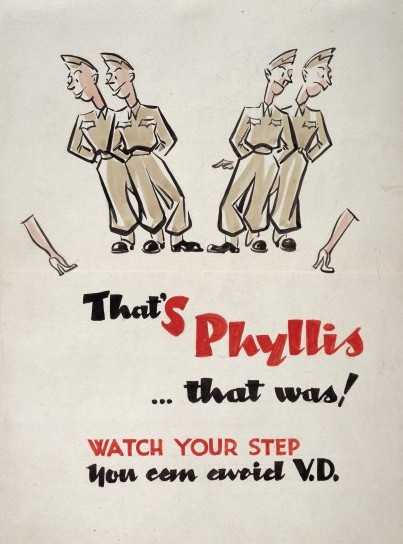

Outbreaks of gonorrhea and syphilis became a marker of the depravity and immorality of non-whites in the colonies. For Jamaican leaders and reformers it was crucial to demonstrate that their island was taking decisive action against venereal disease and that it was leading its backward masses towards health, as well as moral, improvement. During the 1930s, Jamaicans joined a world-wide crusade against venereal disease, reflected in their attendance at the Imperial Social Hygiene Conference in London in 1935. Historian Philippa Levine connects the anti-venereal disease campaigns in the British Empire to progressive visions of modernity. The push to control these diseases was viewed as “the triumph of reason over passion.” Governments across the globe passed coercive laws regulating and surveilling prostitutes as dangerous sources of disease and a threat to military and economic strength. In Jamaica’s context, the focus on black sexuality expanded beyond prostitutes to include all Afro-Jamaican women in the lower classes, and to a lesser extent all black men.

The ways that Afro-Jamaicans were described during the campaign against venereal disease demonstrates the legacy of scientific claims of sexual and racial difference and people’s obsessive examination and description of the black female body. In the Atlantic world, including Jamaica, conceptions of racial difference expressed through the symbol of the black female body were used to justify the horrors of slavery. In the 1770s Edward Long, a scholar of Jamaica, famously wrote of the African female, “an oran-outang husband would [not] be any dishonour to an Hottentot female; for what are these Hottentots?” Long further claimed that slave women could easily give birth in the fields and then continue on with their work, like beasts. Long’s descriptions were widely distributed and made their way into popular understandings of racial difference. Thus, in the 1930s it was not uncommon to read that Afro-Jamaicans were incapable of controlling their baser instincts; sexual promiscuity was a condition of blackness.

Some observers, mainly those of the brown middle class, offered a cultural explanation for the sexual behavior of the lower classes. Even as they sympathized with the lower classes and condemned their economic deprivation, the middle classes lamented the lack of morality in their countrymen and women. Writing in the nationalist newspaper, Public Opinion, the “Philosopher” wrote of his countrymen and women:

They are poor – likely to remain so forever – they are, in the main, illiterate, unable to appreciate the convenience of wedlock to the community; they exist on the merest necessities of keeping body and soul together. So the solitary comfort that rescues them from living death is the sexual. And they indulge the pleasure in a manner that is a logical outcome of their pauperism .

Under the standards of respectability that were central to the British and Jamaican conception of civilized society, the sexual appetites of the black lower classes marked them out as primitive and backwards.

All of these threads of racist iconography combined in the Jamaican campaign against venereal disease. The assumption that even Jamaican children would be sexually active and infected with syphilis, despite clear evidence that they suffered from yaws, starkly demonstrates the extent to which Afro-Jamaican bodies were sexualized. The campaign against venereal disease came to dominate annual budgets for public health, which were slim to begin with, and drew resources away from sanitation, the yaws campaign, and other efforts to ameliorate the impact of poverty and neglect by the British government. Rather than address the deep economic inequalities and abject poverty of the majority of black Jamaicans, the panic over venereal disease placed the blame for disease squarely upon the biological and moral inferiority of the most vulnerable: Afro-Jamaican woman.

During the 1930s, venereal diseases became a means through which colonial elites and moral reformers condemned, surveilled, and made medical interventions against the Jamaican masses. Venereal disease served as a sign of the moral failings of the poor and an excuse for their continued poverty and lack of citizenship within the Empire.

Jill Briggs received her PhD from the University of California, Santa Barbara and is a historian of Science, Medicine and Technology. She is interested in the ways that science and medicine have been implicated in the construction of racial and gender categories, particularly in colonized spaces. Whenever possible, she investigates how those without power and scientific authority have challenged, re-purposed, or rejected Western scientific traditions in order to create their own authority. Jill enjoys the great outdoors and hauling her family behind her to every Natural History and Science museum she can find.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com