‘Sodomy Societies and Sodomy Week-end House parties must not be made legal,’ remarked the Rt. Rev. Christopher Chavasse, Bishop of Rochester, in a letter to Sir John Wolfenden dated 8 August 1956. This observation, buried in the Wolfenden Papers at the National Archives of the UK, merely confirmed the conventional wisdom that gay social spaces should not be tolerated. More surprisingly, however, he went on to express ‘more sympathy with a Curate or Scout-Master who has offended with a boy (horrible though this is: and possibly because I have had to deal with such cases) than with two grown men misbehaving together.’ There are still, of course, many in the Church who are not keen on the idea of consensual sexual relations between men. But, to twenty-first-century sensibilities, and given our current obsessions with child-abusing celebrities, politicians and priests, the suggestion from a respected senior cleric that it might be worse than paedophilia comes as a jolt. So how did we get from there to here? My main aim in this blog is to give an insight into the riches of the Wolfenden Papers, the subject of my recent book. But one of the most interesting and topical ways to do this is to explore what the documents have to say about paederasty and paedophilia—and this will begin to give us an answer as to why the Bishop of Rochester sounds so dated.

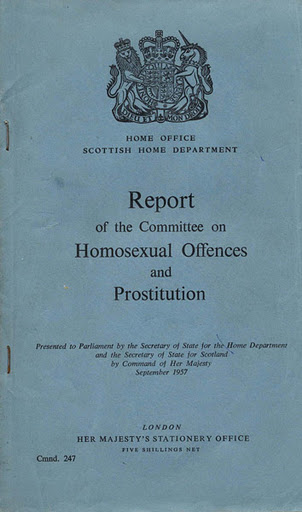

First some background. The government of Sir Winston Churchill, somewhat reluctantly, had set up a Home Office Committee in 1954, chaired by Wolfenden, to investigate the state of the law regarding homosexuality and prostitution. Over the next three years more than two hundred witnesses sent in memoranda and/or appeared before the committee. They included a broad cross-section of official, professional and bureaucratic Britain: police chiefs, policemen, magistrates, judges, lawyers and Home Office civil servants; doctors, biologists, psychiatrists, psychoanalysts and psychotherapists; prison governors, medical officers and probation officers; representatives of the churches, morality councils and progressive and ethical societies; headteachers and youth organization leaders; representatives of the army, navy and air force; and a small handful of self-described homosexuals. The Wolfenden Report of 1957 famously advocated that consenting men over the age of 21 should be free to have sex in private. Less well known is that the Wolfenden Committee Papers provide by far the most extensive array of perspectives we have on how homosexuality was understood in Britain in the mid-twentieth century. The focus is mainly on men, since they were the ones targeted by the law, but some of the witnesses had revealing things to say about female homosexuality, as well.

A key concern for most of the witnesses was the nation’s youth. Could boys’ and youths’ sexual preferences be swayed or corrupted by early same-sex initiation? Did promiscuous homosexuals tend towards paedophilia as they grew older? How should the authorities handle adolescent experimentation during the homosexual phase through which everyone allegedly passed? How could young men best be protected during National Service? To what extent were homosexuals and paederasts in separate categories, with little overlap? These were the questions raised time and again.

Take, for example, the Conservative politician and future Lord Chancellor, Quintin Hogg, Viscount Hailsham, who maintained that the sharp rise in arrests for homosexual offences in recent years could only be explained by greater numbers of older homosexuals seducing the young and vulnerable. ‘Homosexuality is a proselytising religion,’ he wrote, ‘and initiation by an adept is at once the cause and the occasion of the type of fixation which has led to the increase in homosexual practices.’ Ancient Greece and Rome stood as warnings of how societies could become totally corrupted.

This was a contagionist or seduction thesis—suggestive of the remarkable power of homosexuals to produce converts through copulation, and the equally remarkable fragility and vulnerability of heterosexual selfhood. Here is another example: J. P. Eddy, QC, former Stipendiary Magistrate of East and West Ham, London, stated that, ‘[Homosexuality] lives, I believe, on corrupting youth, because I believe that, in general, an adult homosexual is not particularly attracted by an adult homosexual. He wants youth: he wants boys.’ The notion that early same-sex initiation could flip a switch for life was closely allied to a belief in a so-called rake’s progress, a name derived from the series of paintings by Hogarth: the fear that promiscuous homosexuals were constantly on the look out for new ways to spice things up as they aged or degenerated, causing them to turn to youths or boys, paederasty or paedophilia, thereby creating more homosexuals. Sir Laurence Dunne, the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, grounded his opposition to any change in the law in just such a rake’s progress analysis: ‘To countenance homosexual practices in private is playing with fire. Appetites are progressive, and a homosexual sated with practices with adults, without hindrance, will be far more likely to tempt a jaded appetite with youth.’

But the corruption and rake’s progress theses met strong resistance. Most of the medical and scientific witnesses lined up against them, and a memorandum from the Church of England Moral Welfare Council claimed that ‘genuine’ male homosexuals were attracted by older youths and mature men, not by boys: ‘The paederast proper, who seeks none but the young, and often pre-pubertial boy, constitutes a distinct problem, which should not be confused with that of ordinary homosexuality.’ This notion was strongly endorsed by the homosexuals who sent in memoranda and/or who appeared before the committee. One such homosexual was London ophthalmologist Patrick Trevor-Roper. He related his experience at boarding school, where nearly all the boys masturbated each other but didn’t turn out to be homosexual, to indicate his irritation with the conception of initiation. He also stated that, of his acquaintanceship of 150 or more homosexuals, not a single one had ever had a relationship with a boy under 18. Homosexuals, he concluded, were thus quite distinct from paederasts. His fellow interviewee, Carl Winter, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, concurred. He did not know of a single case of an adult homosexual who desired adult males turning his attention to small boys; the thought would be as revolting to most homosexuals as it was to most heterosexuals.

There is a lot going on in these statements. If we accept anything like a Kinseyite spectrum of desires or queer fluidity, the attempt to place homosexuals and paedophiles in separate boxes is probably as unrealistic and artificial as (to paraphrase Kinsey) dividing homosexuals and heterosexuals into sheep and goats. Only a couple of generations previously, a plethora of Uranian poets, artists and Wildean aesthetes, inspired by the ubiquity of age-stratified relationships in the Classical and non-Western worlds, had celebrated ephebophilia (the sexual interest in late adolescents), and they were among the forerunners of modern gay rights activism. Such tastes had by no means disappeared in some queer circles in mid-twentieth-century Britain.

So the attempt before the Wolfenden Committee to draw clear lines was, one might suggest, political rather than merely descriptive, with ‘respectable’ homosexuals denying any evidence that might be embarrassing and jettisoning any men with non-normative tastes who might derail the reform project. Trevor-Roper’s assertion that ‘not a single one’ of his 150+ homosexual acquaintances had ‘ever’ had a relationship with anyone under 18 stretches credibility. Carl Winter’s claim that he didn’t know of any adult homosexuals who had turned ‘to small boys’ is at face value plausible but evasive: what about turning to teenagers? And his own revealing testimony to the committee seriously tested the narrative. ‘[W]hen I was a child,’ he said,

I myself had a relationship of this sort with our gardener, against his will in the first instance. It was I who, as a homosexual boy, seduced our gardener against his will and against his better judgment … [I]t may be the duty of the adult to resist the temptation of the child who is pervertible but it is very often the child who is the determining factor in the case. I think it must be very difficult for certain people, if their interests are at all susceptible in that way, to be attacked by a persistent small boy.

This certainly complicated the developing wisdom that homosexuality and paedophilia were quite distinct. Since Wolfenden turned out to be an exercise in marking out boundaries and firming up binaries—establishing precisely which emerging construction of a homosexual type should be released from the law’s grasp—any suggestion of a fungibility of intergenerational tastes and desires for and by teenagers was inconvenient.

The disavowal of a spectrum of desires or of intergenerational sex by ‘true’ homosexuals was an important strategy of homophile and gay rights organizations in many Western countries in their struggle for acceptance. And it was adopted in the Wolfenden Report, which acknowledged as fact the distinction between homosexuals seeking other adult men and paedophiles seeking ‘boys who have not reached puberty’—thus ignoring completely any intermediary category of seekers after adolescents. This Wolfendenian distinction has endured. A challenge by a libertarian segment of the Gay Left in the 1970s, which argued for the abolition of any age of consent and the embracing of childhood sexuality, gained a certain amount of credence in activist circles, but it was derailed by strong and compelling feminist arguments about unequal power relationships and the need to give survivors of sexual abuse a voice. Six decades on, no Bishop of Rochester could or would express greater sympathy for a paedophile scoutmaster than for ‘two grown men misbehaving together’.

Brian Lewis is Professor of History at McGill University, Montreal, Canada. His recent book, Wolfenden’s Witnesses: Homosexuality in Postwar Britain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), is an annotated selection from the memoranda and interviews in the Wolfenden archive. Its intention is to make this extraordinary resource more readily available to anyone interested in the study of sexuality.

Brian Lewis is Professor of History at McGill University, Montreal, Canada. His recent book, Wolfenden’s Witnesses: Homosexuality in Postwar Britain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), is an annotated selection from the memoranda and interviews in the Wolfenden archive. Its intention is to make this extraordinary resource more readily available to anyone interested in the study of sexuality.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com