Not long after President Clinton decided to keep a polite distance from the soon-to-be best known female White House intern in U.S. history, but still some while before his DNA was lifted from a blue dress, Thomas Jefferson’s DNA made national news. The third president, long rumored to have fathered the children of his enslaved house servant, Sally Hemings, was shown in 1998 to share the genetic material of the youngest of Hemings’s sons. More than a few critics of the sitting president jumped on the story, worrying that the well-timed release of the Jefferson study would somehow give Clinton “cover” by associating his extramarital sex life with that of a much esteemed founder.

The Jefferson “issue” could not be equated to the forty-second president’s non-copulative transgression. But for the sensation-seeking, and even some serious thinkers, past and present were enmeshed. In his 2004 memoir, My Life, President Clinton recalls the moment he learned of the Jefferson study; for it announced an unprecedented predicament, and begged the question: Is there a historical dimension to the manner in which sex plays out in public? Or more precisely, When does sex become a political weapon?

In 1998, Clinton’s critics took immediate aim at what they imagined was a ploy among liberal academics to lighten the burden on a president who was just then on the hot-seat. Later, the founder-worshipping self-taught “historian” David Barton, author of a discredited book called The Jefferson Lies, described the political Left breathing a collective sigh as Clinton was rescued by the Jefferson paternity report: “Such conduct had not diminished the conduct of Jefferson, they argued, so it should not be allowed to weaken that of Clinton.” On the lecture circuit, Barton repeatedly proclaimed that the Left was deluded, and that Jefferson could not possibly have bedded his slave. Liberals were perverting the cause of history in two ways: propping up the morally debased Clinton, and debasing the morally secure Jefferson.

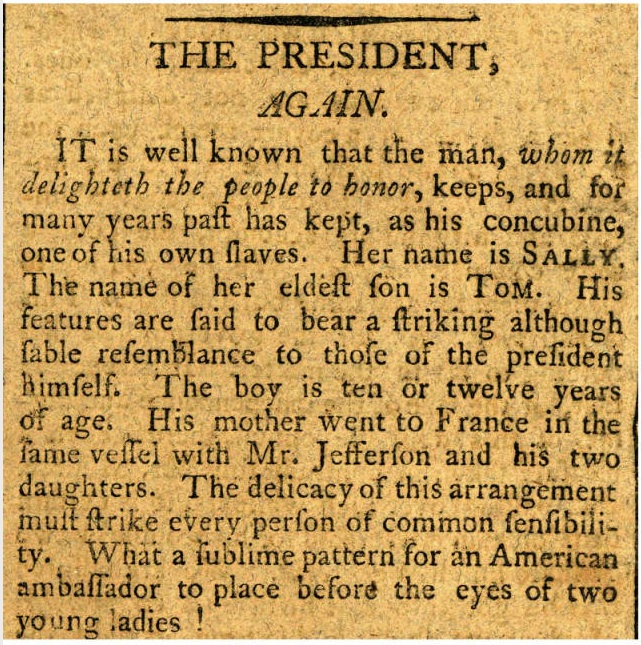

Yet Clinton supporters were stymied by the length of time his affair with Lewinsky went on—close to two years. How careless for a president! A similar curiosity applied to those following the updated Jefferson-Hemings narrative, because the last two Hemings children were born in 1805 and 1807, during Jefferson’s second term as president. The public scandal had erupted in 1802, when hack journalist James T. Callender first published his lurid accusations, bringing smiles to the faces of Jefferson haters and satirical suggestions to the minds of doggerel poets. How careless for a president! Both Clinton and Jefferson had daughters who were virtually the same age as the object of their physical desire—some three decades younger.

“What defined consensual sex?” came next. The culture wars were heating up: “Boys will be boys” was no longer an excuse for male predatory behavior, argued some, while others who defended men’s “nature” protested political correctness. The focus of both scandals was the sexual nature of male power. Did Clinton do more than misbehave? Did he lead the impressionable Monica to believe he would one day leave Hillary for her? Did Jefferson rape his slave for all those years? Or did he love her as he had his late wife? It was hard to nail down nuance in either story. To feed its obsession, the popular imagination was given a double dose: the 1995 movie “Jefferson in Paris,” where a miscast Nick Nolte romanced an alluring Thandie Newton (Sally); and the 1996 blockbuster roman à clef, Primary Colors, by journalist Joe Klein, which featured the Clinton character’s sexual attraction to an underage black girl. The pop-culture view of Hemings cast her as redeemable and granted her agency, which in turn made her slave status less palpable and made Jefferson less culpable.

History tells a less romantic story. Thomas Jefferson had a refined theory, which he advanced at age seventy to former president John Adams, on the subject of sexual impulses. He couched his thoughts in an interpretation of the Greek lyric poet Theognis, who is barely known today, but was once studied closely, in the original Greek, by the college-educated in America. Theognis had issued “a reproof to man,” wrote Jefferson, in calling attention to the care with which the husbandman tends to improvement in the breeding of domestic animals, yet “pays no attention to the improvement of his own race,” marrying for social advantage rather than physical and mental conditioning.

The prospect of eugenically creating a master class interested Thomas Jefferson. And yet, Jefferson concluded after a lengthy exchange of letters with Adams, lust was natural and physical attraction the most human of sensations. No matter how much people wanted to procreate rationally by engineering socially acceptable matches, the Earth would forever be populated by “a fortuitous concourse of breeders.” Geniuses arose by happenstance.

Was he tacitly acknowledging a decades-long sexual congress with his slave? It doesn’t really matter. The point is to show how he thought about sex, and the basis on which he adjudged its power over the mind. Absent love letters to Sally Hemings—who may or may not have been literate, because we just don’t know—this is probably as close as we can come to the sexual impulses of the sexually active Thomas Jefferson. The rest is speculation designed to satisfy the modern taste for filling in gaps about the inner lives of famous forebears.

The vocabulary that attaches to political scandal nowadays tends to fixate on behavioral dysfunction. Less so in Jefferson’s day. As a philosophically inclined public figure, he was lampooned by the political opposition for privately being attracted to an unschooled, lower-class woman of color. It was about class as well as race: her blackness was hyped in outrageously racist tones—she was styled an “African Venus,” dark and mysterious, primitive and restless—but her youth was discounted because sixteen-year-olds were at that time considered marriageable. Different flashpoints. Bill Clinton, by comparison, has been spoofed since 1998 for a wandering eye directed at younger women. According to the satirically drawn popular narrative, this was brought on by a clear-headed, super-smart, non-traditional wife from whose mature competence the good ol’ southern boy needed a respite.

If Jefferson lived in the Age of “Trembling Nerves,” we live in the Age of “Personal Issues.” Our collective critique of Clinton, and the serial adulterers who populate the halls and closets of Congress, concerns a lack of self-control, abuse of power, and moral hypocrisy. There was little concern with Monica’s reputation, just as no one asked how Sally Hemings felt about concubinage.

So we (most of us, anyway) judge past actors with little appreciation for the moral universe within which they operated. In turn, we judge our contemporaries according to rules we make up as we go along, time-trapped, and blind to the inevitability that we will be shorn of our individuality and unfairly generalized. When future historians mull over how a president was impeached on purely partisan grounds for lying about sex, and when they draw on some symbolic text (say, the complete Jerry Springer series) that reduces an entire generation to a pathetic trope, they will indict the best of us as complicit. We, too, watched a lot of mindless television and sat through a lot of Viagra commercials.

What is to be gained by “going after” a historical figure so as to unearth some sexual secret? It’s not as though Lincoln’s syphilis or Grover Cleveland’s out-of-wedlock child or FDR’s, Ike’s, and JFK’s philandering affected their political judgment. Still, sexual behavior matters whenever it leads to potential insights into the relationship between masculine privilege and political authority. Lincoln’s syphilis is a reminder of an America that was a “man’s world” where public figures routinely sought out prostitutes. JFK’s affairs suggest that Camelot was more sordid than what popular myth presents. Mythic distortions demand honest historical re-engagement.

In 1997, at a White House event just months before Jefferson’s DNA test results were made public, President Clinton was curious enough to ask invited guests—an attorney and a historian —whether it was likely that the third president had actually remained celibate after the death of his wife in 1782, when he was not yet forty. What do we do with a founding father as young as that who never remarried? As for his friend and successor as president, James Madison, whom the historical record does not show to have been “involved” at the time of the Constitutional Convention, and who not did not marry until he was past forty, was this the classic forty-year-old virgin? Why, after running off with the married Rachel Robards, did Andrew Jackson have his friends clean up the historical record to promote the narrative of their “accidental bigamy”? History accepted all morally assertive, heroically framed, sexually resistant presidential biographies until the second half of the twentieth century. Then all at once, a “sexual revolution” complicated the nation’s moral encyclopedia, leading eventually to the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal.

The confluence of the Clinton and Jefferson scandals in 1998 is quietly instructive. History is written to serve the present. As memory grows distant from historical events, the task is to avoid a cult-like allegiance to singularities. This caution applies to the study of individuals as well as entire communities. Imagining an unresurrectable Jefferson or Lincoln as messiah-leaders of the moment, exhibiting an uncommon genius or performing political magic (and transcending their bodies), borders on the absurd. Similarly, in the politicized history of sexuality, overestimating the universality of emotional responses is a dangerous kind of complacency. We must continue to resist that tendency to superimpose a false familiarity on historical actors when seeking to reduce the distance between them and us.

Andrew Burstein is the Charles P. Manship Professor of History at Louisiana State University. Among his books are Jefferson’s Secrets (2005) and Democracy’s Muse: How Thomas Jefferson Became an FDR Liberal, a Reagan Republican, and a Tea Party Fanatic, All the While Being Dead (2015).

Andrew Burstein is the Charles P. Manship Professor of History at Louisiana State University. Among his books are Jefferson’s Secrets (2005) and Democracy’s Muse: How Thomas Jefferson Became an FDR Liberal, a Reagan Republican, and a Tea Party Fanatic, All the While Being Dead (2015).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com