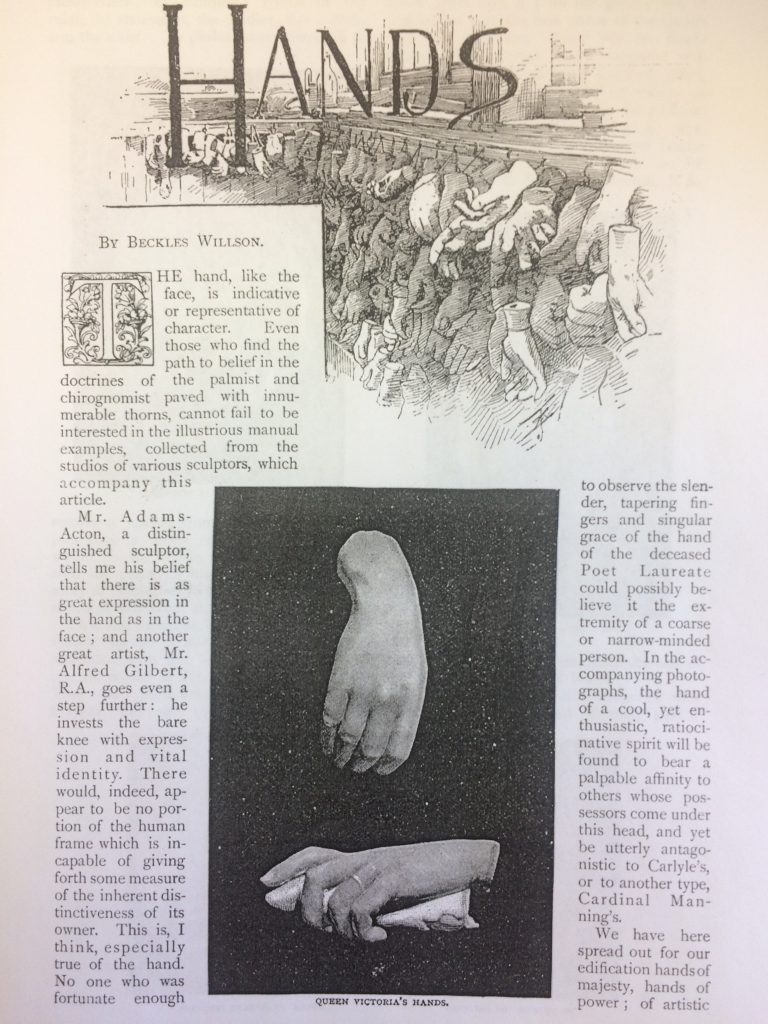

One need not search far to discover that the Victorians adored bodiless hands. Ladies’ hands especially abound throughout the last half of the nineteenth century as motifs and/or subjects in paintings, jewelry, paper goods, sculptures, and decorative objects created to symbolize friendship, love, and sexual desire. During this era, hands became an acceptable object of fixation upon which to leer and project meaning and fantasy, both in themselves and with the spectral body conjured up by one’s own imagination.

In the 19th century, the pseudosciences of cheirosophy or chiromancy, two synonymous terms for palm-reading or palmistry, grabbed the popular imagination, arguing that hands held invaluable information about everything from one’s fate in the realms of love to a person’s character in sexual affairs. Henry Frith and Edward Herron-Allen’s 1883 The Language of the Hand, for example, purports that “Any man who is desirous of entering into connubial relations with any woman, may, by attention to the foregoing rules [of palm reading] obtain an insight.” Herron-Allen’s next volume, Practical Cheirosophy (1887), further instructs readers about deducing sexuality from the hand: “If it is chained [the Line of Heart], the subject is an inveterate flirt,” continuing, “spots on the line denote conquests in love […] you can tell the nature of the person with whom the love-affair has taken place.” In short, hands seduced Victorians both intellectually and visually.

In 1864, James Hadley, a potter-sculptor best known for creating the “Aesthetic Teapot” mocking Oscar Wilde, sculpted a spill vase for Royal Worcester that would inspire countless other porcelain and glassware producers. His creation, often referred to as “Mrs. Hadley’s Hand,” (though proof that the vase is modeled upon her hand has yet to surface), features delicate feminine fingers sporting no jewelry, gently grasping a suggestively phallic vessel intended to hold flowers. The design immediately gained popularity for interior decoration. A myriad of knock-offs, portraying sexualized women’s hands, flooded the market.

When one considers Victorian fashion in all its excess, it is easy to imagine how hands became a fetishized feature: they were frequently in plain sight without covering and often engaged in actions that evoke various sensuality and even sexual acts.

In countless examples of these vases, a disembodied right hand carefully circumvents any obligation to confront a fantasy-derailing wedding ring. “Mrs. Hadley’s Hand” betrays no marital status; the hand could be any woman’s. Even gloved hands, Ariel Beaujot argues in Victorian Fashion Accessories, telegraphed messages about social class and gender, at once evocative and elusive in their erotic potential. Marriage forever haunts the Victorian female hand, especially in novels of the period, as Helena Michie’s The Flesh Made Word contends: “the hand is in itself a synecdoche for more obviously sexual parts of the body that enter into a heroine’s decision about whom to marry.”

Indeed, “taking one’s hand” whether in marriage or an arrangement somewhat less socially sanctioned, acquires additional weight when considering these decorative curiosities that appear grasping flowers, corn on the cob, sea shells, torches – anything conical, vaguely phallic, or suggestively fertile. They suggest the masculine fantasy of a patrician coquette: youthful, slender, and apparently bone- and vein-free – typically sporting a bracelet or rings that advertise social status. In their anonymity and severed-ness, they invite the gazer to entertain possibilities about touch and movement, sparking pliable fantasies from a source that ultimately proves hands-off in its physically fragile, though pleadingly provocative, objectification.

Josh Adair is an associate professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as Coordinator of Gender & Diversity Studies and Director of the Racer Writing Center. His work has appeared in Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, Papers on Language and Literature, and Writing on the Edge. The collection he co-edited with Amy K. Levin, Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities, second edition, will appear from Rowman & Littlefield in 2018.

Josh Adair is an associate professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as Coordinator of Gender & Diversity Studies and Director of the Racer Writing Center. His work has appeared in Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, Papers on Language and Literature, and Writing on the Edge. The collection he co-edited with Amy K. Levin, Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities, second edition, will appear from Rowman & Littlefield in 2018.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com