What is life like for queer people within, and potentially beyond, the culture wars? This was the question asked by the Homosexual Histories Conference held in Melbourne, Australia in late November 2016.

Homosexual Histories is an annual gathering organised by the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives. This year the conference was framed around the explosion of the culture wars—what can be described as protracted debates that occur due to clashes of different cultural values, ideologies or religious beliefs—surrounding queer people and policies in Australian politics over the past year.

The last twelve months, for example, have seen protracted debates around the (eventually failed) proposal to hold a national plebiscite on same-sex marriage. More pressingly, the last nine months have also witnessed intense attacks on the Australian Government’s Safe Schools program, with the program’s co-founder and manager, and conference attendee, Roz Ward becoming a central focus of the debate. As an outspoken Marxist, Ward acknowledged at the conference how her political beliefs turned her into a target, with antagonists connecting Ward’s politics to the Safe School’s program as a way to frame it as ideologically different from the Australian population.

Building on the work of sociologist Janice Irvine, and acknowledging that “culture war encounters are productive events—shaping their protagonists as much as they shape the sexual politics of the time,” the conference aimed to ask big questions around the recent re-emergence of these wars:

What can we learn from past episodes of culture wars around gay liberation, law reform, public health and education? Are there dangers in engaging in culture wars? How can we live well when our terms of existence are being questioned? How can we move beyond engagements that amplify anti-LGBTIQ voices?

The conference began with a keynote titled “Our Bodies, Our Archives” from Annamarie Jagose, a queer theorist at The University of Sydney. Jagose provided an essential historical critique of the way in which queer theory, in particular, engages with culture wars as forms of “productive events.” She argued that queer theory has become too focused on gesturing towards the future—to ‘beyond’—without grounding itself in the present. She suggested that the archives could be an antidote to this problem. The archives, she argued, ground us in sentimentality and a feeling of authenticity, something that is much more real than the vague gesturing of ‘beyond.’

In turn, Jagose argued that the very concept of the culture wars was somewhat misguided, largely because, as the title of the conference suggests, we are always trying to get ‘beyond’ them. She challenged participants to rethink the ways in which they viewed the conference itself. We must, she argued, be able to situate ourselves in both the past and the present, rather than always looking to ‘beyond.’

In the second keynote on the second day of the conference Melissa Wilcox, a sociologist of religion from the University of California Riverside, dove into the ethics of “doing” queer history. Wilcox described her research on The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence; “a leading-edge Order of queer nuns.” Established in the United States in the 1970s the Sisters—now a worldwide organisation—comprise of orders of queer nuns who engage in political campaigning, safer-sex awareness and fundraising for queer organisations and campaigns.

In detailing her research, Wilcox explained the ethical issues that arose in documenting a number of ‘myths’ within the sisterhood that were either presented in contradictory manners by the research participants or could not be independently verified. While described by Wilcox as often harmless, these sorts of myths in ways created their own ‘wars’ about the culture and ideology of the organisation. Sisters, for example, disagreed and debated with one another, whether founding members of the organisation were also sex-workers, with different ideological views on whether or not this fact (if it is true) should be promoted. In disagreeing about their history, Sisters interrogated the modern culture of the organisation.

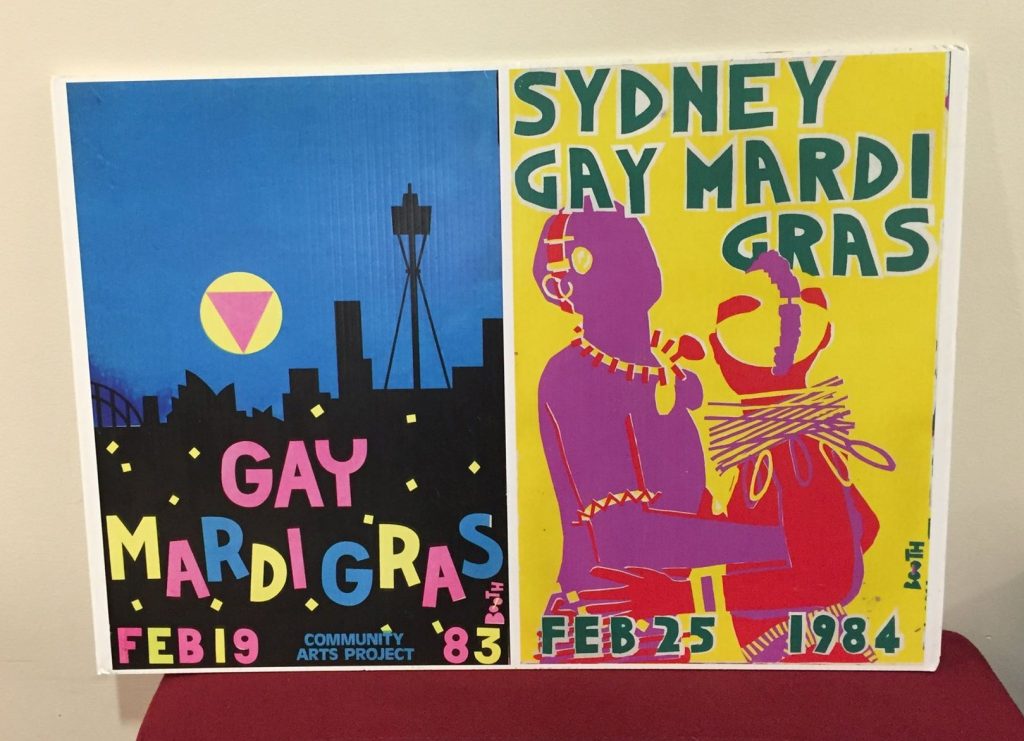

These discussions continued through the conference. At one of many workshops, panelists Graham Willett, Philomena Horsley, and Paul Ven Reyk reflected upon the Australian culture wars surrounding queer populations in the 1970s and 1980s. They presented fascinating accounts of early gay activism in Australia, reflecting on, for example, the National Summer Offensive for Gay Rights in 1980—the first truly national event to promote gay and lesbian rights, organised after the violence at the first Mardi Gras in 1978. This event was seen as a major step forward for activists who, feeling empowered, made gay rights a national issue. Panelists also analyzed how the growth of the gay rights movement emboldened ideological foes, in particular The Australian Festival of Light, a religious organisation founded by now New South Wales state MP Fred Nile. Panelists noted how they often took a ‘light hearted’ approach to the work of the Festival of Light, engaging in stunts that often lampooned and mocked the organisation. This included campaigners dressing in drag to stake out Festival of Light events, people engaging in ‘kiss ins,’ and the creative use of banners and other props to disrupt their events.

At the end of this discussion I asked for the panelists’ reflections on why, at least from my perspective, queer organisations have been unwilling, or unable, to use these more light-hearted types of tactics in today’s culture wars. This question created immense debate. Both panelists and audience members weighed in, with many arguing that this hesitancy is due to the culture wars of today being more ‘serious’ than they were of years past. One panelist reflected that in the 1980s, queers ‘had nothing to lose,’ making these styles of advocacy appealing.

It is here where some of the challenges of how we situate ourselves within the culture wars, and in particular the importance of situating individual lives and experiences within these historical moments, became apparent. The first day ended in a plenary discussion between Dennis Altman, Carol D’Cruz and Crystal McKinnon, titled “Culture Wars: Then and Now.” The somewhat unstructured discussion unfortunately became quite heated, particularly after Graham Willett argued from the audience that on any measurable legal or social outcome queers are better off in Australia today than they were ten years ago. This caused some anger from both audience members and some panelists, with some claiming that it was easy for Willett to make such a statement as a ‘white gay man.’

The challenge presented here was multi-pronged. While Willett’s argument was based on measurable legal and social outcomes, the critique of this approach is that it did not necessarily take individual experiences into account. There is no singular queer identity, and it is therefore impossible to generalise in the manner in which Willett did. Progress is situational, and while we have certainly seen advancements in legal rights for queer people in Australia, there have also been significant challenges, primarily with the advancement of neoliberal economics (with cuts to public services for example directly impacting queer people) and with increasing tensions in regards to race relations.

However, linking back to Annamarie Jagose’s initial challenge, this exchange also highlighted the complex questions we face when centring ourselves solely within the present when engaging with the culture wars, while not being able to step back to reflect on the past. As Roz Ward, the central participant in Australia’s current culture war over gay rights, acknowledged numerous times, being stuck in the middle of these events is extraordinarily draining. Being caught up in these culture wars— as many attendees of the conference were — can make it difficult to step back and view the important historical arc of these forms of productive events.

Beyond the Culture Wars presented participants with an important challenge: how can we use the archives and queer history as a way to centre ourselves in the present, and in turn to move ‘beyond’? The difficulty of this endeavor, however, was laid bare throughout the conference, with participants engaging in debates about the very nature of our historical and present reality. To be able to move beyond the broader culture wars, therefore, first requires a greater understanding of our own positions.

Simon Copland is a freelance writer and a PhD candidate in Sociology at the Australian National University. He writes on gender, sexuality and politics. He can be found online on Facebook at Twitter.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com