In November 1871, a mere six months after the fall of the Paris Commune, a play opened at the famous Odéon theater. Seemingly apolitical in tone, the melodrama appealed to an audience hungry for sensation and eager for distraction. This appeal was quite understandable in the wake of the recent Prussian siege and Paris’ subsequent revolt against the French Third Republic, in which the working-class revolutionaries of the capital ultimately faced defeat, slaughter, imprisonment, and exile. For the theater-going public, the desire to move past the “année terrible” must have been palpable, and the producers of The Baroness aimed to please. Despite the play’s seeming avoidance of contemporary politics, The Baroness nonetheless offers an unexpected entry point into the fundamental nature of the modern French nation-state. The Baroness reflects the centrality of disability and sexuality to the notion of citizenship and how both became sources of anxiety for men in nineteenth-century France.

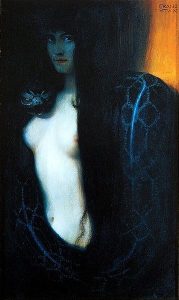

The play’s plot revolves around the machinations of the eponymous baroness, Edith, who sets her sights on marrying an elderly French aristocrat. Having already lost one fortune in an inheritance dispute and now the mistress of a penniless doctor, Edith wants to have her cake and eat it too—she will marry the old man, wait for him to die, then reunite with her true love as a rich widow. The physical health of Edith’s new husband, however, proves hardier than she had hoped, and she soon starts orchestrating his internment in a psychiatric institution. She is on the verge of convincing the courts to grant her control of the unwilling patient’s finances when he escapes the institution and strangles his duplicitous wife with her own necklace. The symbolism of this violent act was rich for the necklace looked like a snake and was a gift from Edith’s lover, the doctor.

The story of the nefarious Edith and her “mad” husband fits comfortably within a familiar cultural narrative about the crisis of masculinity in France at the turn-of-the-century. Historians have shown that the increasingly sedentary lives of the middle classes, the growing visibility of women in the public sphere, and the falling birthrate combined with the national humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War to threaten French men’s sense of virility.

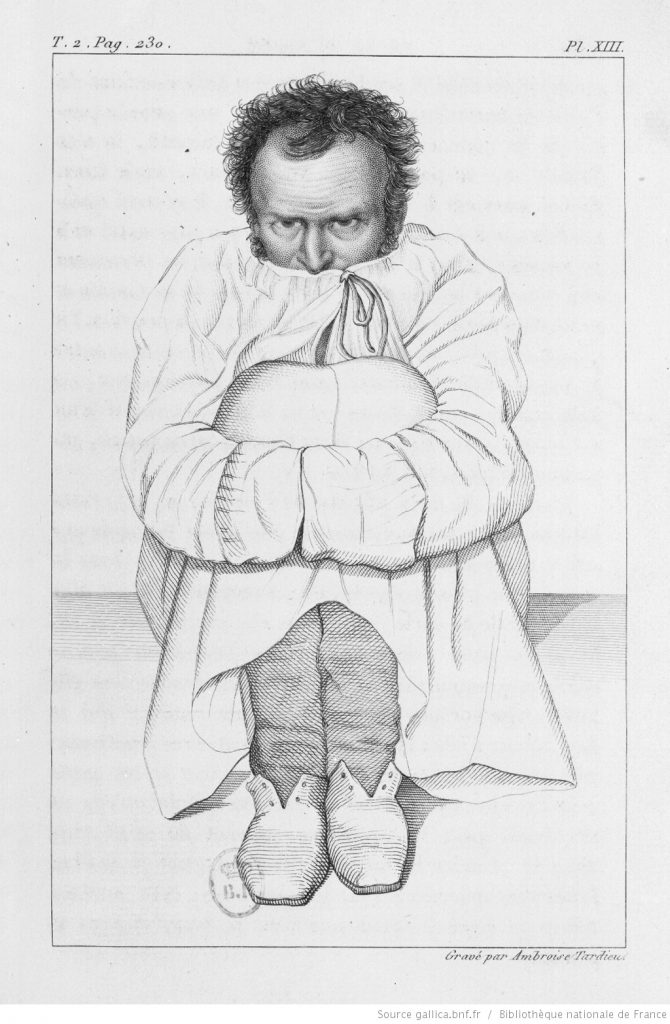

Yet, in order to fully appreciate the play’s significance we must further situate its plot within the history of disability—specifically the medicalization of mental illness, which began in earnest in France during the Revolution of 1789. The founder of French psychiatry, Philippe Pinel, supposedly unchained the inmates of the Parisian asylums of Bicêtre and the Salpêtrière during that tumultuous time. While historians have concluded that the scene was largely apocryphal, the myth nonetheless symbolized a new understanding of madness as a curable condition: people deemed insane were now patients rather than prisoners. The French state legitimized this conception of mental illness in 1838 by passing a law provisioning a nation-wide network of public asylums staffed by medically trained professionals. Over 40,000 French men and women would be housed in psychiatric institutions by the 1870s.

It is impossible to separate the consolidation of what disability scholars call the medical model, in which mental and physical impairments came to be understood primarily as deficiencies in need of cure, from the creation of the liberal nation-state. The same optimism that propelled the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century inspired the notion that mad people could regain their reason under the proper care. An absolutist monarchy needn’t concern itself with the rationality (or lack thereof) of its subjects. Conversely, the expectation of active citizenship—not just with respect to voting rights, but to military conscription, and less formal mechanisms of political participation as well—necessitated the unprecedented involvement of the French state in the lives of mad people. The logic of industrial capitalism also encouraged increased concern over psychiatric rehabilitation, the idea being that a cured patient would prove a productive worker. What we now term psychiatric disability—once essentially a private matter—had become a very public concern by the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

If The Baroness is any indication, many French people met this turn of events with skepticism and considered the asylum system dangerously open to manipulation. As the historian Aude Fauvel has shown, worries over unjust asylum commitment and other abuses contributed to a wave of anti-psychiatry during the second half of the nineteenth century. Calling asylums “modern Bastilles,” critics loudly proclaimed the undemocratic nature of asylum psychiatry despite the profession’s revolutionary origins. The play was part of this wider cultural critique, and its plot unabashedly drew upon contemporary causes célèbres in its lurid depiction of marriage, madness, and murder.

Much of the unease brought about by the medicalization of mental illness coalesced around its implications for family life. Critics worried that an accusation of insanity could undermine the authority of husbands and lead to their loss of autonomy. In addition to legislating the availability of public asylums, the 1838 law also regulated how a person might find him or herself institutionalized. The primary method of commitment involved the request of a family member and the signatures of two doctors; the family could then pursue a separate legal process called interdiction in order to strip the patient of their financial rights. This is precisely the chain of events set in motion by Edith in The Baroness. In an environment where insanity could lead to the loss of one’s fortune, not to mention liberty, it is little wonder that accusations of mental incapacity were sometimes wielded as weapons in family disputes—especially when married women had limited property rights and divorce remained illegal until 1884.

All this suggests that the nineteenth-century emergence of psychiatry as an influential medical specialty caused anxiety for elite men, even if it also served as a bedrock of their authority. On the one hand, asylum doctors gave the veneer of scientific legitimacy to widely held beliefs equating manliness with rationality, thereby providing legislators an excuse to deny individual rights to those deemed inherently irrational—namely, women and colonial subjects. At the same time, when rationality became the definitive prerequisite for citizenship, men found themselves having to live up to this new and rather exacting standard. The loss of reason, or the appearance of such, had profound consequences. The Baroness capitalized on this state of affairs by combining the legitimate fear of unjust asylum commitment with a nineteenth-century bogeyman, the overtly sexual and ruthless woman.

In reality, there is little evidence to suggest that wives were any more likely than husbands to orchestrate the internment of a spouse in a psychiatric institution for financial gain. Many people—of all ages, classes, genders, and sexual orientations—found themselves committed to asylums against their wills, often at the instigation of one relative or another. Indeed, the medicalization of mental illness surely had more dire consequences for people who did not conform to normative gender roles than those, like Edith’s husband, who did. It is nonetheless telling that the creators of The Baroness chose this particular combination of villain and victim. Despite all its melodrama, the play sent the message that irrationality was a liability that not even masculinity could overcome.

Jessie Hewitt earned her Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis in 2012 and is now an Assistant Professor of history at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia. Her research focuses on the gender and class dimensions of psychiatric treatment in France from the French Revolution until World War I. She has published on women asylum directors, as well as on the role of madness in the French divorce debates of the 1880s. She is currently writing a book about asylum psychiatry and the family in nineteenth-century France. Jessie tweets from @jessie_hewitt.

earned her Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis in 2012 and is now an Assistant Professor of history at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia. Her research focuses on the gender and class dimensions of psychiatric treatment in France from the French Revolution until World War I. She has published on women asylum directors, as well as on the role of madness in the French divorce debates of the 1880s. She is currently writing a book about asylum psychiatry and the family in nineteenth-century France. Jessie tweets from @jessie_hewitt.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com