Interview by Lauren Gutterman

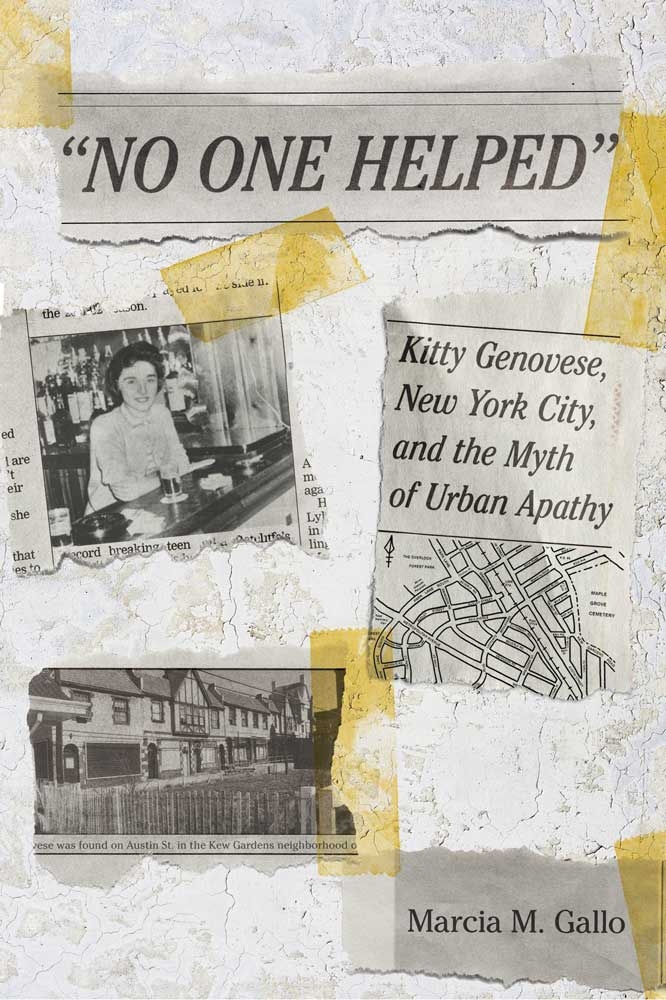

Marcia M. Gallo’s book “No One Helped”: Kitty Genovese, New York City and the Myth of Urban Apathy (Cornell University Press, 2015), the winner of a Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction (Publishing Triangle) and a Lambda Literary Award (LGBT Nonfiction category), examines the infamous murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese, a young lesbian bar manager, in Kew Gardens, Queens, in 1964. “No One Helped” restores Genovese’s humanity, and critiques the “myth of urban apathy” that newspaper coverage of Genovese’s murder created in the midst of widespread struggles for racial and social justice. Gallo’s book also reveals that the Genovese story contains not one, but multiple tragedies including Genovese’s rape and murder itself; the erasure of her subjectivity in the news; the isolation and police treatment of her lesbian lover; the criminal justice system’s failure to serve the black female victims of Genovese’s murderer Winston Moseley; and the demonization of Genovese’s neighbors in Kew Gardens who supposedly heard her screams, but failed to help her as she lay dying in the vestibule of her apartment building. At a moment when “inner cities” are once again being deployed in the media as symbols of unchecked violent crime and social disintegration, the history Gallo traces is vital.

Lauren Gutterman: The 1964 rape and murder of Kitty Genovese has attracted sustained attention on the part of journalists, artists, activists, and others. Can you tell us what motivated you to revisit this much-told story?

Marcia Gallo: It was based on a childhood memory and very little information, but the resilience of the name “Kitty Genovese,” and the terrifying story of uncaring neighbors intrigued me. As an impressionable small-town preteen, I was fascinated by descriptions of Genovese as a young Italian-American woman who managed a bar and drove a red Fiat around New York City. For me, those few facts about her screamed “rebel.” I wanted to learn more. And I wondered, what other norms had my paisana challenged?

Also, it was a story that did not fade. Her awful death was mentioned routinely from 1964 on, whenever the media reported on situations in which good people did nothing in the face of evil. But very little about her life was included in the stories about her death.

About ten years ago, I hoped to write a biography of Kitty Genovese. Although I was fortunate to have been able to interview three people who knew and loved her—Mary Ann Zielonko, her lover; Angelo Lanzone, her best friend; and Bill Genovese, her brother—there was nothing in Kitty’s own voice—no diary or letters or photographs—that I could access. Ultimately, I began looking at the story behind the story. It became clear to me that the emphasis on apathy in the Genovese story meant that everything else, including Kitty herself, was sacrificed.

LG: Not until decades after Genovese’s murder did her then-lover, Mary Ann Zielonko, come forward publicly about their relationship. What is the significance of Genovese’s story for LGBT history?

MG: In 2004, my years of casual infatuation with Kitty Genovese became what some might call an obsession. That year, I was stunned by the revelation in a New York Times article that she had been in an intimate relationship with a woman. But this time, the freelance reporter assigned to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the crime, Jim Rasenberger, wrote a long feature story that made Kitty Genovese the center of the story. He tracked down Kitty’s “roommate,” Mary Ann Zielonko, who agreed to talk with him. “We were lovers together,” she said. “Everybody tried to hush that up.” Zielonko added a painful detail to the story when she revealed that her lover was killed early in the morning of their first anniversary.

The story suddenly took on special interest to queer people; one lesbian journalist referenced the infamous and brutal 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard and claimed Kitty Genovese as iconic to LGBTQ communities. In 2012, the Advocate magazine placed the murder at the top of its list of “12 Crimes That Changed the LGBT World.”

The other part of the Genovese story with relevance for LGBT history is one that rarely is mentioned and has yet to be fully explored. It is likely that the one person who arguably could have saved Genovese’s life was a friend, Karl Ross, a gay man. He witnessed the second fatal attacks on her but was initially immobilized by what he saw and heard, compounded by extreme fear of the police. He did call the local precinct and contact another neighbor, who immediately rushed to her side. She cradled Kitty in her arms as they waited for the ambulance, but Kitty died on the way to the hospital.

LG: The public erasure of violent crimes perpetrated against black women is an important theme in your book. Can you explain how your study of Genovese’s murder brought you to this issue?

MG: It became clear that the official version of the crime was an intervention into what people such as New York Times journalist A. M. Rosenthal saw as a dangerous turn toward militancy among civil rights protestors. At the same time that he was warning about the “sickness” of apathy, the Times also was running stories about the increasing protests, vigils, walkouts, and demands by activists to end segregation in New York City. However, Rosenthal equated anti-racist activism with “impersonal social action.” Coming in the spring of 1964, his words were potent weapons at a time of intense racial protests in the U. S., especially in northern cities.

Just weeks before the first of the 1964 uprisings, Genovese’s accused killer, an African American family man with no police record named Winston Moseley, went to trial at the Queens County Courthouse. After the jurors returned their verdict of guilty and later prescribed the death penalty, cheers erupted from the spectators. Moseley’s execution was postponed and his death sentence reduced to life imprisonment in 1967. But the story doesn’t end there. In 1968, Moseley escaped from prison. While hiding out at a vacant house, he captured and sexually assaulted Zella Moore, a young black woman, and threatened to kill her children if she reported the attacks. Despite these threats, Moore contacted the people who owned the house and Moseley surrendered to the FBI within days. But instead of being rewarded for her bravery, Zella Moore was charged with aiding a felon. As Barbara Sims, the only black lawyer in the Erie County district attorney’s office at that time, told the press, “If this had been a white woman raped, do you think they would have brought her into court and charged her with a crime?” She refused to prosecute her, and the charges against Zella Moore ultimately were dropped because of community outcry. The nearly universal silence in the media about this part of the story astounded me!

Race also intersected with gender and sexuality in the starkly differential treatment given to Moseley’s other murder victim, Anna Mae Johnson. This disparity was first brought to my attention at the Queens County Courthouse. A young black female clerk commented that although there was great interest in Kitty Genovese, no one seemed to care much about Moseley’s other murder victim—“the black woman.” She was referring to Anna Mae Johnson, whom Moseley stalked, stabbed, and raped as she lay dying and then set her body on fire just two weeks before he went after Kitty Genovese. Although he was indicted for both Anna Mae Johnson’s and Kitty Genovese’s murders, Moseley was never prosecuted in the Johnson case, a failure that is not addressed in almost all accounts of the story despite the fact that Anna Mae Johnson and her family never received justice.

LG: You are very critical of A. M. Rosenthal and The New York Times‘ coverage of Genovese’s murder and the supposed 38 witnesses to her attack who did nothing. Your book highlights the ways that the myth of urban apathy that Rosenthal and The Times constructed erased and even demeaned the Civil Rights Movement. How can your book help us to understand and perhaps respond to contemporary efforts to undermine leftist and anti-racist activists?

MG: The myth of urban apathy is an example of the privatization of responsibility, which continues today. In his writings about the crime, Rosenthal not only condemned the people of Kew Gardens; he also denigrated the necessity of collective action for social change and challenged any efforts to hold law enforcement accountable. The framework he used in creating the myth of the 38 witnesses foreshadowed the neoliberal political values that have become much more embedded in our culture since then.

Rosenthal’s narrative seemed off to me until I read his book, Thirty Eight Witnesses. It promoted the idea of a city, and a nation, gripped by indifference. I also spent hundreds of hours reading copies of the New York Times and local papers to see what was being reported in the months leading up to the crime and immediately afterward. It became clear to me that Rosenthal used the Genovese story as a platform from which to demonize activists, black and white, that were demanding an end to racial segregation and police violence.

In addition, an accurate depiction of Genovese and the woman lover who mourned her would have shifted the focus of attention to her sexuality and torpedoed the Times’ emphasis on apathy. Rosenthal’s attitudes about homosexuality were well known. “Where did all these…these queers come from?” he asked at a news meeting shortly after becoming Metropolitan Editor. The answer resulted in a landmark December 1963 front-page story headlined “Growth of Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern” that left no doubt that homophobia was the order of the day and the Times reflected it. A number of former staffers and scholars have documented the antigay bias found at the paper in the early 1960s, noting at least a dozen articles from 1960 to 1964 that promoted the “pathology” of homosexuality to the paper’s readers.

LG: What are the most important legacies of the coverage of Genovese’s case?

MG: The story today always includes the well-known reforms that followed in the crime’s wake, such as the creation of the 911 emergency response system—which didn’t exist the night Kitty Genovese was attacked—and the development of psychological theories of “bystander syndrome.” Rarely, however, is the Kitty Genovese case noted as foundational to movements against sexual violence.

The genesis of the “38 witnesses” myth is useful here. As the Queens police went knocking on doors in the hours and days after the crime in 1964, some of Genovese’s neighbors refused to speak to them. It was from these notes that the official number of supposed “witnesses” was created. Many said that they heard screams yet saw nothing, but one nearby couple admitted that they thought the screams they heard were due to “a lovers’ quarrel” and so decided it was none of their business. It would take at least a decade before cultural attitudes about intimate partner violence would be challenged as part of a political movement.

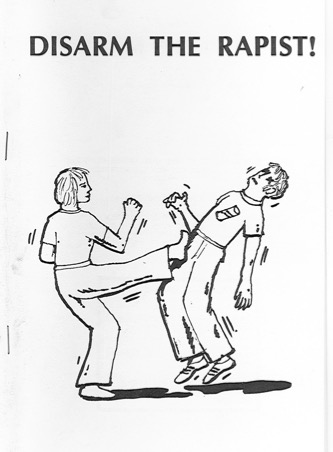

In addition, although the details of Moseley’s sexual attacks on Kitty Genovese were included in court documents, the story of the case as promoted by the New York Times did not mention them. It was not until 1975 that local and national feminist activists insisted that rape and sexual violence were significant parts of the story, one of its most important if under-reported legacies. For example, in 1977 feminists at Michigan State University in East Lansing organized the Kitty Genovese Memorial Anti-Rape Collective and distributed a fifty-seven-page self-defense pamphlet titled Disarm the Rapist! Nearly 20 years later, New York area feminists created a self-defense guide and published it as a zine dedicated to Kitty Genovese. And Genovese was referenced in the recent reauthorization of the federal Violence Against Women Act and utilized in training sessions on many college and university campuses.

Marcia M. Gallo teaches and serves as MA Program Coordinator in the Department of History at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Her first book, Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Rights Movements (Carroll & Graf, 2006; Seal Press, 2007), won the 2006 Lambda Literary Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the Publishers’ Triangle Judy Grahn Award. Gallo has authored articles and contributed essays to a number of edited collections, such as Bodies of Evidence: The Practice of Queer Oral History (Boyd and Roque Ramirez; Oxford, 2012) and Breaking the Wave: Women, Their Organizations, and Feminism 1945-1985 (Laughlin and Castledine; Routledge, 2011). She also is the current President of the Southwest Oral History Association.

teaches and serves as MA Program Coordinator in the Department of History at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Her first book, Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Rights Movements (Carroll & Graf, 2006; Seal Press, 2007), won the 2006 Lambda Literary Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the Publishers’ Triangle Judy Grahn Award. Gallo has authored articles and contributed essays to a number of edited collections, such as Bodies of Evidence: The Practice of Queer Oral History (Boyd and Roque Ramirez; Oxford, 2012) and Breaking the Wave: Women, Their Organizations, and Feminism 1945-1985 (Laughlin and Castledine; Routledge, 2011). She also is the current President of the Southwest Oral History Association.

Lauren Gutterman is Assistant Professor of American Studies, History, and Women’s & Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently revising her first book manuscript, Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which examines the personal experiences and public representation of wives who desired women in the United States since 1945. Her writing has appeared in The Journal of Social History, Gender & History, and The Public Historian.

Lauren Gutterman is Assistant Professor of American Studies, History, and Women’s & Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently revising her first book manuscript, Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which examines the personal experiences and public representation of wives who desired women in the United States since 1945. Her writing has appeared in The Journal of Social History, Gender & History, and The Public Historian.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com