Interview by Taylor Antoniazzi, Zöe-Blue Coates, Tim Cunningham, Alexie Glover, Rachel Lallouz, Morghan Watson, and Shaun Williamson

Edited by Rachel Hope Cleves

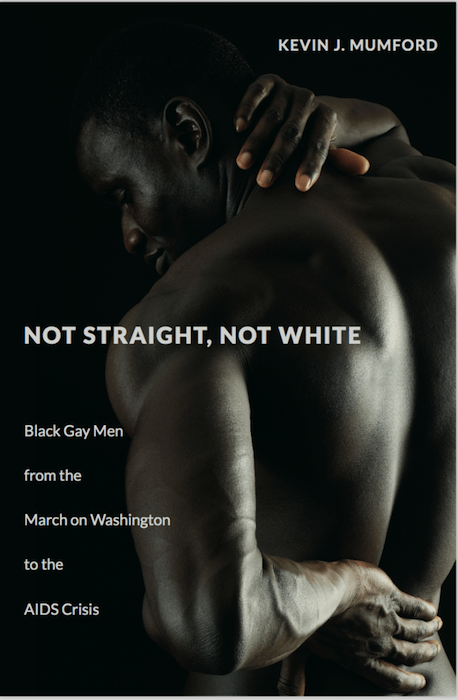

It may seem surprising that Kevin Mumford’s Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men from the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis (UNC, 2016) is the first monograph to focus exclusively on the history of black gay men in the twentieth-century United States. But after you read Mumford’s account of the nearly insurmountable struggles that his subjects faced in formulating their identities as black gay men, the challenges confronting the historian of their experience becomes clear. I assigned Not Straight, Not White to students enrolled in my spring 2017 graduate/undergraduate seminar, “The History of Gender, Sexuality, and the Body,” because it hit on key themes for the second half of the twentieth century, including the Civil Rights Movement, the Gay Rights Movement, and the impact of HIV/AIDS. In addition, it retold these events through the lives of a cast of characters almost completely unknown to my students. Although I came to class with foreknowledge about the lives of Bayard Rustin and James Baldwin, I had just as much to learn as my students did about Mumford’s less famous historical subjects, like Brother Grant-Michael Fitzgerald, Joseph Beam, and James Tinney. Mumford’s book offers a much-needed recuperative history of a marginalized community, retold through a series of indelible portraits of courageous men, many of whom died far too young. As the students’ questions demonstrate, the stories of these men will stick with readers long after they close the book’s covers.

Williamson: How did you choose the subjects of your biographical chapters? What are the benefits of using biographies to gain insights into institutions?

Mumford: I started this research with a grant from National Endowment for the Humanities where I had proposed to work on the Joseph Beam papers, and planned to write a full-scale biography of him. But I also started to research more about Beam’s social context, and through this work I discovered newspaper reporting on a failed gay rights bill in Philadelphia involving race issues. When I went to read the transcript of the city council hearings on the measure at City Hall, I learned about Grant-Michael Fitzgerald, a black gay Catholic leader, and started to piece his life together. Eventually I came upon news of other figures, and I was soon engaged in collective biography, whilst remaining interested in documenting the cultural contexts that constrained the lives of black gay men. I wanted to be able to explore the dynamics of coming out for black men, and also to explore their intimacies, especially since I was learning about the ways that society objectified black gay sexualities. I felt that biography would offer an excellent way to examine the impact of societal discrimination on the individual—what it means to struggle against marginalization and how it feels to fail. I wanted to illustrate the real, everyday consequences of losing out at the intersection of racism and homophobia. I didn’t want to write a victimization narrative, but at the same time I wanted to show how we never thrive under circumstances where we are dismissed or silenced because of our intersectional identities.

Cunningham: Can you discuss your archival strategies for recuperating the lives of little-known queer historical figures? How did “dissemblance” and “the politics of respectability” create archival silences, and how do we go about rebuilding “a genealogy of black gayness” in the face of such silences?”

Mumford: This is a very complicated question. First, I would say that I have written about a particular constellation of black gay men, and obviously not all black gay men nor a total collectivity by any means. These men share some key unique aspects—the first of which is that they have archival materials. Each of them has a historical record in part because they were activists and were therefore atypical as well as very special. Even so, I also write about quasi-fictional figures, such as an actor playing himself as a black gay hustler in a one-man performance, or the archetype of the “black gay stud” depicted over and over again in pulp pornography. At other times, I trace the crucial history of black masculinity in social science or in Black Power rhetoric, and how social movements and urban crises uniquely impacted the meanings of black gayness. Most of all, I discovered that I enjoyed writing about heroic people, even though I definitely see their problems and flaws and mistakes. I live in the gay district in Chicago, where there are ubiquitous markers of rainbow “pride,” and I can say that doing this book has taught me something new about pride–and reaffirmed its importance in making a meaningful life.

Coates: Considering how black and gay identities have historically been structured by racism and homophobia, what possibilities exist for an independent black queer subjectivity?

Mumford: When you say “independent,” I take that to mean a kind of autonomous subjectivity, which is a question at the heart of my book. First off, this question is important because it recognizes something that, before my book, few if any scholars would have thought to recognize: namely, that racism and homophobia are powerful streams of subordination—and that their historical combination has served to dehumanize and demoralize. So that even in my university, my colleagues in any number of fields have expertise in studying racial formation, or queer theory, or the history of social movements, but they don’t appear to consider how these spheres of intellectual activity might overlap. And therefore, except for the important paradigm of intersectional feminism, there is no foundation for studying black gay men in historical contexts. There is some theorizing, and this is important, but moving beyond ideas to the analysis of structures means giving some concreteness to the marginalization. We have some memoirs and autobiographical accounts from black gay men. Yet, as a historian, I am able to see the operation of power and the constraints of stigma from a vantage that even these very imaginative and astute black gay voices could not quite apprehend at the time.

Glover: Several of the figures you examine found their vocations in a religious setting. How important is it to recognize the role that religion played in the homophile movement?

Mumford: When I talk about the book, I always express my surprise at the role of religion in the histories of black gay men, but I also admit that I shouldn’t be surprised given the crucial role of the black church in African American history, and particularly for the social activism of the postwar U.S. Yet, (white) LGBT studies have not paid much attention to religion during this period, even though it must have also mattered to white gay men. However, I found that my African American subjects were often searching for a sense of community, and the church provided them with an obvious place where they might locate a sense of belonging. Perhaps the church also assuaged their internalized guilt about being gay and also spirituality provided them with resilience in a society that misunderstood or vilified them. Black gay men faced a great deal of animus and had a few places in which to seek refuge—and the church was both crucial and hostile, both spiritually rich and institutionally abusive.

Lallouz: Can you speak more to the relationship between black lesbian feminists and black gay men, and did you find any evidence of animosity between the two as took place between white lesbian feminists and white gay men?

Mumford: I did not find very much cooperation between lesbians and gay men over the longer chronology, but I did point out that Joseph Beam, a 1980s activist who receives a lot of my attention, relied on the mentorship of writer-activists such as Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith. He definitely socialized with black lesbians in Philadelphia, particularly at a bar called the Smart Club. Indeed, because of his deep personal respect for lesbian feminists, Beam was able to innovate in ways that produced new modes through which he could talk about and represent the experience of being black and gay. In a stroke of luck, we have Beam’s voluminous papers preserved at a major archive. He saved hundreds of pages of his correspondence as well as carbon copies of outgoing mail, and so we have the record of a relatively obscure activist performing crucial cultural work. His archive illustrates the constraints of the closet on a single individual—he dropped out of school and for a while was totally isolated. His papers also demonstrate the resourcefulness and the dedication of someone who strived to improve conditions for others like him and to build a “black gay revolution,” as he put it.

Antoniazzi: I found this to be the most heart-wrenching book I’ve been assigned to read this semester. How did you process the emotions of the research?

Mumford: Thank you for this question, because it makes me feel as if I’ve connected with at least one reader. There is a lot of writing today on queer affect and loss, and the history of emotions—some of it interesting to me, some self-indulgent and off-putting to me. So I wanted to illustrate black emotions with a historical study—and figure out how to relate some of the pain and sadness, as well as joy and courage, that I found in these black queer lives. These men experienced the real pain of loss, not the fashionable facsimile. (Real tears.) The first time I opened the first file of the Beam papers, sitting in the Schomburg Library in Harlem, I began to weep and weep. I was peering into the life of someone whose personal instincts were so brave and generous, but also someone who was often defeated. There were rejection letters, unpaid bills, and diaries with poems describing painful isolation. I think we (as students in the humanities) all feel this way at some point in our careers– that we are trying to make a difference for the better–but we also feel defeated, especially when you are living at the intersections of queerness and race or disability or trans.

I also found finishing the book to be very therapeutic, and I feel validated by praise and the audiences that have shown interest in my work. For a very long time, I didn’t have any confidence in my research or writing and then, after a workshop hosted by a dear colleague, I felt like I was onto something and that I had the talent to bring this study to fruition. Because the book is so close to me, and in fact is sometimes about me, it is very painful when I confront unjust rejection or dismissal. I am very sensitive to the intersections of homophobia and racism and it pains me when I experience this, especially from various segments of the profession or the university that professes to be progressive!

Kevin Mumford is professor of history at the University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign. He is the author of Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century; Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America; and most recently, Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men from the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis, which was awarded the Stonewall book prize from the American Library Association and is a finalist for the Lambda Literary Prize in LGBT Studies and the Randy Shilts Prize for LGBT Non-Fiction this year. Mumford also received scholarly awards from the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association for his research on race and gay rights.

Kevin Mumford is professor of history at the University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign. He is the author of Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century; Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America; and most recently, Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men from the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis, which was awarded the Stonewall book prize from the American Library Association and is a finalist for the Lambda Literary Prize in LGBT Studies and the Randy Shilts Prize for LGBT Non-Fiction this year. Mumford also received scholarly awards from the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association for his research on race and gay rights.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thank you for this interview and posting, and now I want the book!