Moderated by Carolyn Bronstein and Whitney Strub

In honor of the publication of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars, we invited Jennifer Nash, Joe Rubin, Gillian Frank, and Whitney Strub to participate in a roundtable on sexual representation in the 1970s United States. In this second round, the contributors reflect on pornography’s widespread appeal to diverse populations. Be sure to check out part one!

Pornography appeals broadly to a wide audience of users, from the industry’s bread-and-butter white, heterosexual, Christian, married consumers featured in Gillian Frank’s work, to sexual outlaws seeking an authentic vision of their desires and a sense of legitimacy and community. Joe Rubin points out that the makers of adult films, much more so than their Hollywood counterparts, represent a diverse group across race, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic background, and levels of artistic training and experience. Jennifer Nash helps us see that the performers in adult films are not always the stereotypically innocent ingénues who fall unwittingly into adult films. Instead, they include performers who consciously choose this work and appreciate its psychological, emotional, physical, and monetary rewards. From your perspective, why does pornography speak so effectively to so many across socioeconomic, religious, racial, cultural, and gendered lines? What is the basic appeal of pornography that your work reveals?

Jennifer Nash

My understanding of pornography’s pleasures is that they are always myriad, despite scholarly work which has presumed the simplicity of the pornographic spectator, and presumed this spectator’s pleasures are individual (and masturbatory). In other words, pornography “speaks sex” (to borrow Linda Williams’ phrase) so effectively because it always speaks in the plural. In my earlier work, I emphasize the array of pleasures pornography generates, including pornography’s capacity to make us laugh with its absurd narratives, clumsy dialogue, and mechanical music. Even in its capacity to arouse, pornography does this work in multiple ways. As I argue in my book, this arousal can be sexual, but it can also be political, aesthetic, and visual. We can take pleasure in pornography by reading it “with the grain” and “against the grain,” by identifying or disidentifying with its characters. Part of my claim, then, is that pornography deserves to be understood as a complex genre, much as the melodrama, the horror, the romantic comedy are.

In my mind, pornography’s basic appeal is that across time, it has told a story. Pornography captivates us by narrating sexual pleasures, however thin that narrative might be, and however much that narrative might rely on widely circulated racial and sexual stereotypes (here, pornography is not unlike any other popular genre. Perhaps pornography is distinct in how explicit—in every sense of the word—its reliance on stereotype is). Even in our contemporary moment where many argue that pornography’s story-telling days are over, pornography continues to narrate a sexual world to viewers, allowing us to fill in stories from context (Is it Brazil? Is it a living room? Is it an urban apartment?).

Joe Rubin

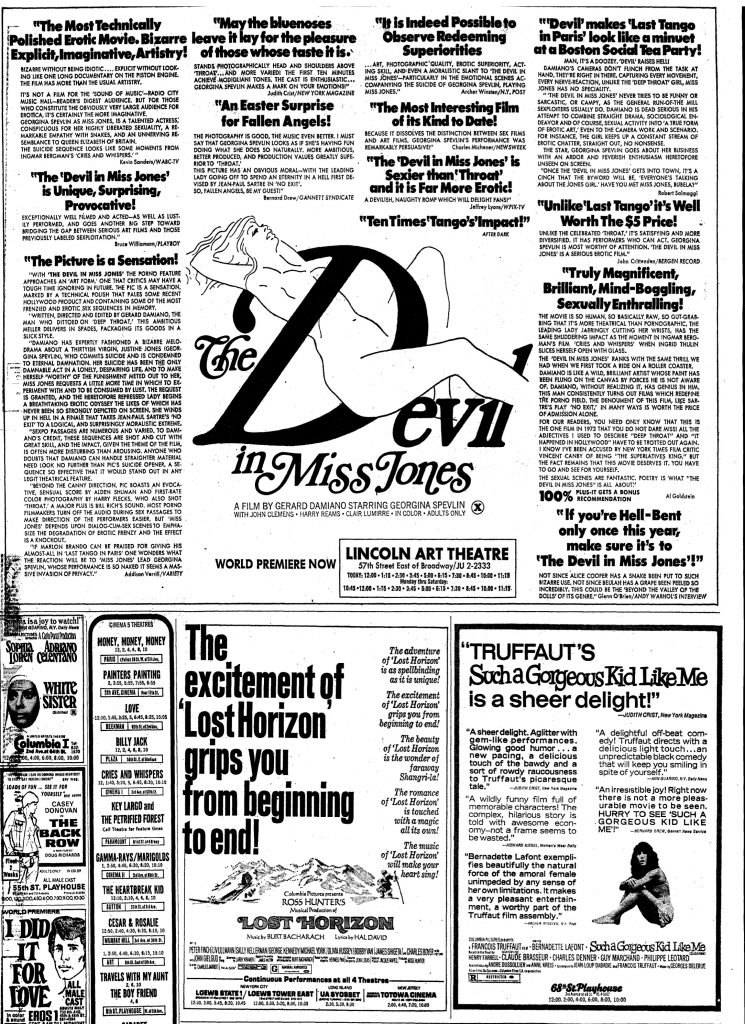

This is a difficult question to address because we’re speaking in this book about work created prior to the internet age. How this material is understood and interacted with in the 21st century is, in many ways, very different from how it was approached in past decades. Hardcore theatrical feature films are a good example. In the 70s, these productions existed alongside, albeit still thematically somewhat separated from, ‘mainstream’ cinema. Looking only at the American hardcore feature film industry, open any metropolitan newspaper of film industry trade publication produced in the 70s through mid/late 80s, and there is sure to be an ad, notice, review, or article involving a hardcore movie.

Although it would be easy to assume that this pervasiveness of hardcore feature films in pop culture was solely due to American’s preoccupation with sex, that is a very reductive way of approaching the sensation of theatrical hardcore. Those merely interested in visual depiction of fornication could easily visit an adult bookstore for loops, magazines, or photo sets, or, if one was fortunate enough to live in a large urban area, find a venue featuring a live sex stage show. Theatrical hardcore is distinct from these other erotic representations and performances because its cultural positioning as cinema.

The (literal and figurative) positioning of a film, like Rinse Dream’s 1982 hardcore dystopian fantasy, CAFÉ FLESH, as a ‘pornographic’ film in some theatres and a ‘midnight/cult’ film in others upon its theatrical release, demonstrates the cultural fluidity enjoyed specifically by hardcore features. While it’s also true that very few such films saw such diverse screening types during the 1970s and 80s, there was a perpetual attempt on the part of filmmakers and audiences alike to simultaneously approach these works as both utilitarian (to serve as a means of sexual arousal) and as ‘underground/transgressive’ art films which, by their nature, pushed boundaries.

The social justice movements of the 1960s-80s further necessitated the prevalence of hardcore films throughout the US. Watching sex films in a public setting was an artistic and political statement. It implied a conscious push against censorship, a revolt against the conservative and sexually repressive cultures that had dominated the country in the previous decades. Going to a ‘porn’ theatre was almost a form of ‘coming out.’ Even if the films themselves could not live up to their progressive hype, they still had the power to give their audiences the feeling of being rebellious (an irony given that ten years later, these films would be pitted against the wave of anti-porn feminists whose ideological stance was that they were not transgressive but rather proliferating misogyny).

The contemporary, more privacy-oriented porn culture, which privileges solitary viewings, has retroactively stigmatized public performance of sexually explicit cinema as something shameful that was only necessary due to technological limitations (an argument which always forgets the prevalence of 8mm loops, created specifically for solitary viewing). In doing so, much of what was previously unifying has been rendered obsolete.

Gillian Frank

For historians, recovering why a text appealed to an audience is a difficult endeavor. It requires finding those rare archival sources that capture audience reactions. It requires carefully reading and interpreting these audience responses, which are seldom straightforward expressions of desire.

My research for my chapter on Evangelical women’s marital advice manuals yielded hints about what motivated some readers to purchase books that promoted eroticism and female submissiveness as the keys that unlocked the doors to happy marriages. Authors of advice books regularly published positive responses to their writing. These letters, unsurprisingly, affirmed the authors’ own narratives. As a result, we have the smallest of peepholes to view the complex reactions to Evangelical marital advice literature from the 1970s.

When women wrote to the authors like Darien Cooper and Marabel Morgan, they discussed their difficult home lives and how they were looking for comfort, intimacy, conflict resolution, sexual excitement or harmony in their homes. In an era of rising divorce rates and against the backdrop of feminist critiques of the institution of marriage, Evangelical women’s marital advice books told readers that they were both the cause of and solution to their own problems. Wives had to change who they were and submit to their husbands’ wishes. Crucial to enacting that marital transformation was a wife’s ongoing sexual performance, which began at the breakfast table, and ended in the bedroom.

Wildly successful instruction manuals with titles such as The Total Woman, The Electric Woman, You Can Be the Wife of a Happy Husband, and The Spirit-Controlled Woman incorporated elements from 1970s pornographic culture and endorsed a wide range of nonprocreative sexual pleasures, such as mutual masturbation, extensive foreplay, and a range of sexual positions. “I learned,” wrote one of Cooper’s readers, who claimed to have become the wife of a happy husband, “that there are no sexual perversions when a wife is satisfying her husband’s sexual desires and needs.”

Although it is not possible to reconstruct exactly how couples appropriated the advice from a cohort of white middle-class evangelicals, the best-seller status of their literature and the media fanfare that greeted it suggests a wide consideration of their ideas. When Marabel Morgan advised her readers, “You can be lots of different women to him. Costumes provide variety without him ever leaving home,” her audiences responded with enthusiasm. And they made connections to pornography. One Illinois housewife wrote to Morgan about her attempts to follow the advice in The Total Woman: “I now own some nightgowns and pajamas that would not even be allowed in a[n] X-rated movie. Why? Not for me. I feel very uncomfortable in them but I wear them for him, and when it makes him happy, I am more than happy.”

If anything, the archive teaches us that the appeal of the 1970s pornographic texts was not only about debased desires. It was also about complex social needs. Countless women read marital advice books, and unknown numbers took up the authors’ invitation to heal their marriages by improvising sexual scenarios based on the book’s scripts and on a wider pornographic culture. These private sexual performances bespoke women’s own cultural investment in preserving marriages, which themselves represented their senses of self-worth, their identities, and their expectations for happiness and security.

Whitney Strub

I just want to briefly amplify a few things already said here about the diverse pleasures offered by pornography, not all of which are even necessarily sexual. When Jennifer Nash envisions the participatory experience of reading the mise-en-scène for context clues (“Is it Brazil? Is it a living room? Is it an urban apartment?”), it resonated with my experience of watching Seventies porn not for the sex as much as the location shooting in my own piece, which looks at the narratives of urbanism in straight and gay hardcore (straight films, I argue, colluded in the reactionary “urban crisis” framework of the era, while gay films challenged that lens by reminding viewers that one group’s crisis is another’s liberation). So while I certainly appreciate a variety of bodies meeting in different pleasurable configurations, my own spectatorial pleasure often derived from catching Peter Berlin at a precise address on Polk Street in That Boy (1974), or from the audacity of a threesome on top of the First Federal building in Hollywood, shot from a helicopter in Howard Ziehm’s Harlot (1971).

Thom Andersen’s brilliant, polemical essay-film Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) argues that every film is an accidental documentary of its own circumstances of production, and it’s rarely more true than in the 1970s hardcore—where the sex, as we know from Linda Williams and others, is always mediated, but the scenery is often less so than in more reputable films, if only by dint of hurried, not-quite-legal production that left little time or money for set design. Andersen himself understood this hardcore urbanism (what Jeffrey Escoffier, in looking at gay 70s hardcore, has recently labeled “homorealism”)—his very title attempts to reclaim Los Angeles from the abbreviated horror (in his view) of Fred Halsted’s gay landmark LA Plays Itself.

Finally, to return to Joe Rubin’s emphasis on the material conditions of porn-watching in the 70s, such writers as Samuel Delany have shown how the films themselves were only part of the experience for many attendees. Cruising was the most obvious non-viewing pursuit, but somewhat lost in our internet age is also the sheer pleasure of discombobulation that could come from wandering the labyrinthine halls of a dark, expansive, unpoliced grindhouse movie theater (we get a different disorientation online, of course). Just last week, I strolled the halls, nooks, and crannies of the Fair Theatre in East Elmhurst, Queens, with screens showing everything from Bollywood to hardcore porn to Star Wars. There’s virtually nothing like it left in 2017 (film buffs might imagine Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, filtered through Jacques Nolot’s Porn Theater), but it powerfully invoked a particular historical set of sensations, too easily lost if we focus only on texts themselves, outside their concrete settings. Unbeholden—or at least, less beholden—to the classical Hollywood mandate to actively invest emotionally but observe passively, Seventies porn offered uniquely embodied viewing experiences to its many different audiences.

Carolyn Bronstein is the Vincent de Paul Professor of Media Studies in the College of Communication at DePaul University, and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of History and the American Studies Program. She is the author of Battling Pornography: The American Feminist Anti-Pornography Movement, 1976-1986 (Cambridge, 2011) and coeditor with Whitney Strub of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars: American Sexual Representation in the 1970s (University of Massachusetts, 2016).

Gillian Frank is a Managing Editor of NOTCHES: (re)marks on the History of Sexuality. He is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. Frank’s research, which has appeared in journals such as Gender and History, Journal of the History of Sexuality and Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and Reproductive Politics in the United States Before Roe v Wade. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

Gillian Frank is a Managing Editor of NOTCHES: (re)marks on the History of Sexuality. He is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. Frank’s research, which has appeared in journals such as Gender and History, Journal of the History of Sexuality and Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and Reproductive Politics in the United States Before Roe v Wade. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

Jennifer C. Nash is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (Duke University Press, 2014), which was awarded the Alan Bray Prize by the GL/Q Caucus of the Modern Language Association. She is also the editor of Gender: Love (Macmillan). She has published articles in journals including GLQ, Social Text, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Review.

Jennifer C. Nash is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (Duke University Press, 2014), which was awarded the Alan Bray Prize by the GL/Q Caucus of the Modern Language Association. She is also the editor of Gender: Love (Macmillan). She has published articles in journals including GLQ, Social Text, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Review.

Joe Rubin is an American film archivist and co-founder of the acclaimed home video company, Vinegar Syndrome. His work to restore and preserve American hardcore feature films has been featured in The New York Times, Playboy, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

Joe Rubin is an American film archivist and co-founder of the acclaimed home video company, Vinegar Syndrome. His work to restore and preserve American hardcore feature films has been featured in The New York Times, Playboy, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark, where he co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011), and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark, where he co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011), and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com