Petra Anders

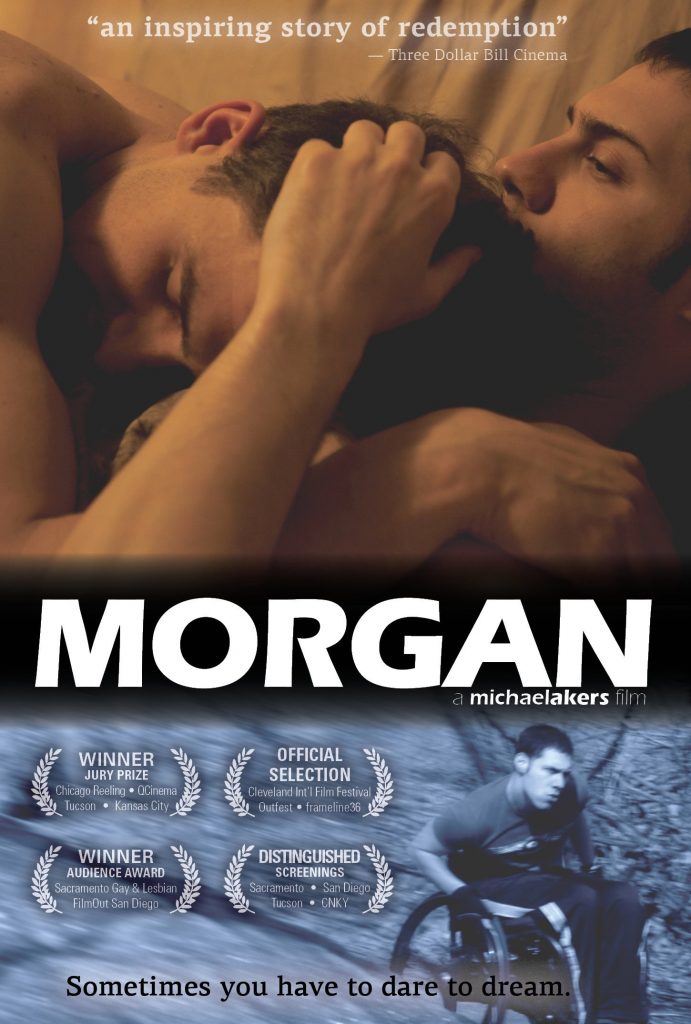

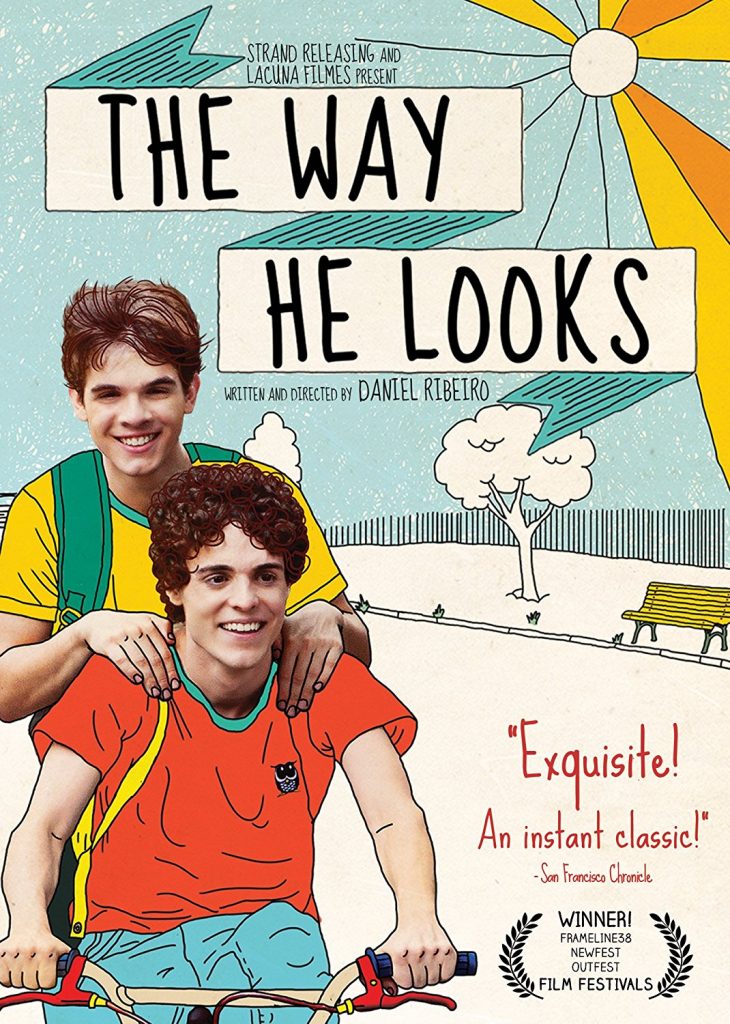

Male characters with disabilities are often portrayed in mainstream films in one of two broad ways: either as evil men with sexual abnormalities or as good guys whose disability prevents them from having fulfilling sex lives. Two films, however, challenge these all too predictable combinations of disability and sexuality. The US film Morgan (2012, directed by Michael Akers) and the Brazilian film The Way He Looks (Hoje Eu Quero Voltar Sozinho) (2014, directed by Daniel Ribeiro) are examples of how films can represent gay male characters with disabilities who develop positive self-images and social identities.

Akers’s drama focuses on Morgan, a young gay athlete who became a wheelchair user after a severe accident. Morgan wants to prove that he can be a top athlete even as a wheelchair user. Such drive pushes him to ignore the physical risks of his intense training while his stubborn behavior puts his new relationship with his lover, Dean, at stake.

Akers, the director/writer, and Sandon Berg, the film’s producer/writer, explore Morgan and his lover’s exploration of their sexuality. Morgan and Dean want a fulfilling relationship in which they can also express their physical desires. But even if in Dean’s eyes Morgan is still ‘sexy as hell,’ Morgan himself remains skeptical. His disbelief is most obvious in a conversation with Dean after they have sex for the first time. Morgan believes he ‘was a winner’ when he was able-bodied, implying that disability makes this impossible for him. Still, Morgan’s physiotherapist encourages him that his spinal cord injury does not have to keep him from having sex.

Changes in Morgan’s self-understanding are fostered by a ‘romantic overload’ at the beginning of their relationship as Dean quickly adapts his apartment to Morgan’s needs. Whereas Morgan had not earlier wanted to show his affection for Dean in public, in the last scene he breaks through his insecurities by declaring to Dean, ‘I want the whole world to know how I feel about you’. While Morgan was sure he had lost everything in the accident, with Dean he finally announces, ‘I’m a whole new man’, and is shown playing basketball in his sports wheelchair. He no longer needs to prove something to himself or others, but simply enjoys having a good time with Dean. In the end Morgan’s relationship with Dean persuades him to rethink and redefine his identity as a person with disability, an athlete, and a gay man.

Just like Akers, director Daniel Ribeiro lets his disabled character express his sexual identity without stigmatizing it. The main character in Ribeiro’s drama is a teenager named Leo, who is blind and has a crush on his new classmate Gabriel. In comparison to Morgan, Leo is used to living with a disability but his feelings for Gabriel are new to him. Leo realizes through his attraction to Gabriel that he is gay. In a way the film plays it safe at this point. Any teenage boy in a coming-of-age film would enjoy spending time with the person he has fallen in love with. Then again, the blind teenager can be like every other boy or girl who falls in love for the first time. When Leo’s classmates mock him for being blind, the filmmakers do not turn him into the stereotypical odd-one-out or the lonely, ugly ‘other’. Instead, Leo’s best friend, Giovana, and Gabriel are there for him. All three of them are comfortable with their self-identities, whether they are able-bodied or disabled, gay or straight. None of them are presented as a generic ‘other’ or as a metaphor for difference.

Both films feature disabled gay characters who aim to develop what Rebecca Maskos calls a ‘wertetransformiert[e], emanzipiert[e] Identität’ [an emancipated identity with transformed values]. She argues that the social perception of disabled people is based on stereotypical dualisms. These dualisms are reflected in disabled persons’ identities on the one hand, and judgments made by society on the other. Using this concept, we can recognize Morgan’s and Leo’s freedom from psychological conflict (when the sense of self for people with disabilities differs from the social perception created by able-bodied people). But Morgan and Leo do not define themselves through inadequate concepts of identity constructed by the able-bodied environment.

These two films are useful for understanding histories of sexuality and disability because the filmmakers refrain from employing old stereotypes of characters with disabilities as either evil and sexually abnormal or as unable to enjoy sex and physical intimacy at all. Akers’s and Ribeiro’s films successfully counter many other films’ ‘othering’ of people with disabilities and/or non-heteronormative sexual identities. As Maskos points out, an emancipated identity with transformed values enables people with disabilities to accept their disability without either devaluating or idealizing it. This also includes their sexual identities.

Petra Anders is Research Assistant to the AKTIF Research Project at the TU Dortmund, Germany. Her research interests include Disability and Gender in films and Disability Studies. Her book Behinderung und psychische Krankheit im zeitgenössischen deutschen Spielfilm [Disability and Mental Health in Contemporary German Film] was published in 2014 with Königshausen & Neumann. She also contributed to Benjamin Fraser’s Cultures of Representation: Disability in World Film Context (2016). She tweets from @PA_PetraAnders.

Petra Anders is Research Assistant to the AKTIF Research Project at the TU Dortmund, Germany. Her research interests include Disability and Gender in films and Disability Studies. Her book Behinderung und psychische Krankheit im zeitgenössischen deutschen Spielfilm [Disability and Mental Health in Contemporary German Film] was published in 2014 with Königshausen & Neumann. She also contributed to Benjamin Fraser’s Cultures of Representation: Disability in World Film Context (2016). She tweets from @PA_PetraAnders.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com