Jerry T. Watkins III

Queering the Redneck Riviera recovers the forgotten and erased history of gay men and lesbians in North Florida, a region often overlooked in the story of the LGBTQ experience in the United States. Jerry Watkins reveals both the challenges these men and women faced in the years following World War II and the essential role they played in making the Emerald Coast a major tourist destination.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

Watkins: After World War Two there was money to be made from tourists – lots of it. In the process of separating those tourists from their cash and rebranding Florida as “The Sunshine State,” a variety of people no longer fit the wholesome or family-friendly image. Queer people, as well as prostitutes, gamblers, and moonshiners, were made scapegoats at times of economic insecurity. Almost nothing drummed up more publicity, votes, or religious capital than a highly publicized denunciation or raid of a queer space (bars, cruising grounds, house parties, etc.). Like so many sand castles, their existence on the Emerald Coast was then scrubbed and forgotten.

While making larger arguments about the relationships and intersections of sexuality, tourism, and capitalism in mid-twentieth-century Florida, my book is at its core about people carving out space for themselves in a hostile environment. It is about the people that didn’t evacuate to the metropolis for “safety” but staked their claim to a place in “The Sunshine State.” I end the book with the following words: “Whether on the sand or the back roads, queer folks have made this part of Florida their home. They’ve been an essential part of making North Florida the colorful tapestry that it is today. They lived, they laughed, they cried, and they loved. They queered the Redneck Riviera.”

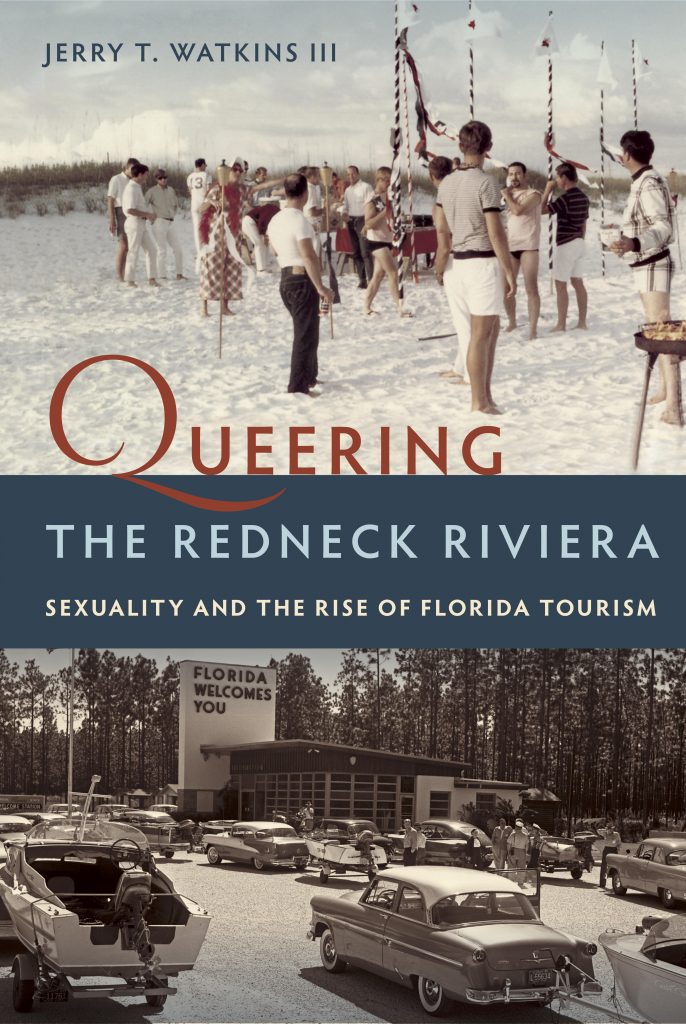

Why people will want to read my book is always a difficult question to answer. I’ve been so steeped in it for so long that it is hard to “sell it.” A lot of locals and visitors to this part of Florida will find a wealth of new information. I’ve tried to keep the book accessible for popular audiences whilst giving scholars enough to chew on. Anyone interested in Florida history or larger American tourism studies will find the book a worthy addition to their libraries. Scholars of the South or queer folk in the South will find it valuable because the beach was a microcosm of the larger South. Lastly, I’ve tried to keep the levity. It was not all doom and gloom on the Gulf Coast. As the front cover indicates, there was campy fun to be had on the sand.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions do you still have?

Watkins: I was born and spent the first 21 years of my life on the “Redneck Riviera” (also known as the “Emerald Coast” or “Miracle Strip”). After I decided to pursue history as a major and then career I kept returning to memories of my first gay bar experience and the question of how my small hometown had supported a gay bar for decades. To my young mind, the décor seemed to be from the 80s and in 2002 that looked like such a very long time ago. As it turns out, the bar opened in 1965, which further piqued my curiosity. Scratching the surface of that question opened a queer world that I had no idea existed. I soon realized that I wanted to write the kind of book that I needed as I was coming of age.

I think every historian is plagued by the questions that cannot be answered. There are so many people that I wanted to interview but couldn’t. Some were long dead, and at least one man died the week before I arrived for a research trip. The men who started the Emma Jones Society passed away as I was beginning the research and before I knew of their existence. I wanted to see where some of the people arrested ended up and to follow their life stories. But even with the connectivity of the Internet many of the people I encountered merely disappeared.

NOTCHES: This book is clearly about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Watkins: One of the other primary themes is tourism. This includes the tourists and locals that serve them, but also the structures of power that facilitate or foreclose certain kinds of tourist experience. Part of my argument challenges the narrative of a benign marketing campaign to turn Florida into a “family friendly” paradise. A line in another book on Florida that seemed to imply that suddenly Florida became “safe” inspired that part of the argument. I think I audibly rolled my eyes when I read the line. There, in the space of a few lines, the author erased entire populations and glossed over the very real damage done to people who didn’t fit in. I wanted to show the flip-side to the goofy and self-deprecating tourist promotions. The anxiety generated by competition on the open market for tourists coupled with larger Cold War anxieties produced a desire for “safety.” This “safety” did not include queer people.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use, were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

Watkins: I began by walking into the Fiesta Room Lounge one afternoon and introducing myself. This introduction connected me with some of the men who provided oral histories. From there the research expanded out to newspapers and archives. Historians of Florida are particularly lucky that Jim Schnur sued to have the records of the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee opened to researchers. Though the existence of the committee is abhorrent, the documents provide thousands of pages of interrogation transcripts. Though conducted under duress and limited to those who came into contact with the state, they offered a roadmap for gathering places, cruising spots, and other community sites. Armed with dates and locations, I kept returning to the newspapers and oral histories. The biggest challenge was the distance between my sources and me. One of the downsides to being based so far from one’s sources is that research trips have to be well planned out and tightly focused. For instance, I spent a week in Los Angeles at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives combing through letters to ONE Magazine and Mattachine looking for anything written by people from the lower south. There were 27 boxes to get through, and I only had a week to do it. It meant skimming, and I’m sure I missed things.

There were so many exciting discoveries, but two particularly stand out. The first was Tom Baker. In chapter two I write about a police raid on a public toilet in 1961. It was standard practice at the time to print names and addresses of those arrested for homosexual acts, so I had a list of names. Many were middle-aged in 1961 and unlikely to be living, but two were 18. In early interviews, several people said: “you should talk to Tom, he’s still around somewhere.” Not only was Tom still around, but he was also willing to talk and was generally a wealth of information. He was so gracious with his time and his memories. The second was Ray and Henry Hillyer’s photo albums. In chapter five I write about the Emma Jones Society and the beach parties and conventions held in Pensacola that brought thousands of gay men and lesbians together every 4th of July. I had incredibly rich descriptions of the drag shows and events, but no photos. I was giving a talk in Pensacola about those parties, and afterward Kurt Young walked up with three photo albums in his hand. Though I could not publish most of the photos due to privacy concerns, they provided a wealth of information about the events and the organization. One of the images is on the cover of the book.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Watkins: Many stories were either left out or just left on the cutting room floor for lack of evidence. In the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, I came across a particularly fabulous letter from a man who was raised in Pensacola (one of the cities I write about) and was committed to the state mental hospital because of his sexuality in the early 1960s. He ultimately spent two years there. Because of privacy laws, etc. I couldn’t find other information about him or track down others who were there. I tried to write a chapter about his experience, but my reviewers rightly suggested I get rid of it because of how thin it was. He just didn’t seem to work anywhere else. He is in a shorter article I wrote for Sex and Sexuality in Modern Southern Culture, edited by Trent Watts. Women and people of color are also not covered as much as they should be. The source material for those communities was sparse, and I couldn’t ever quite seem to make the right connections for oral histories. I also wanted to make the book more current and include much of the activism and community building work in the 21st century. I did some interviews and some of the research, but it all kept drawing the book away from the main arguments. So rather than tack on extra chapters and produce a clunky text I kept the narrow focus. The reviewers were especially helpful in this process.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

Watkins: I decided to switch majors from marketing to history in 2002. I wasn’t sure what kind of history I wanted to study, but I knew that working in marketing would destroy my soul. I signed up for Alecia Long’s History of Sexuality course because it seemed like it might be exciting and it worked in my schedule. It blew my mind. She taught me that not only did sexuality have a history but that it was exciting and worthy of serious study. That course set me on the path to where I am today.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Watkins: From a student’s perspective, the most attractive feature is the length. Though short, it is a useful way into topics covered in courses as diverse Southern History, Tourism Studies, American Studies, or History of Sexuality. I would assign it with Julio Capo’s Welcome to Fairyland or pair it with Robert Camina’s documentary Upstairs Inferno. It would also match well with Stacy Braukman’s Communists and Perverts Under the Palms or with the documentary The Committee.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Watkins: LGBTQ history is quite literally being erased from the public domain. Though we can get married, queer people continue to face violence, discrimination, and oppression. The erasure of our lives had substantial consequences for the people I write about and continues to have for the generations that came after them. Without drifting too far into the problematic triumphalist “we’ve always been here” rhetoric, I think it is important to understand and show how people fit into a community’s history. It is all the more important to show how they challenged seemingly hegemonic power structures around them. If one young queer kid picks up my book and they realize they aren’t alone, then that’s all that matters. The flip-side of that, people have a nostalgia for the way Florida “used to be in the good old days.” It is important to show those people that “The Sunshine State” was not as white, straight, or clean as people imagined.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Watkins: I’ve been interested in musical theatre for a very long time — shocking I know! Over the last several years I’ve been interested in the ways theatre translates history and makes specific comments for every generation, Cabaret being the most obvious example. As I’ve continued to think, I’ve become very interested in grassroots queer theatre. In the summer of 2017, I saw a production of Yank! in London and the creators credited Alan Bérubé’s Coming Out Under Fire as the inspiration for this World War Two love story between two male soldiers. That experience started me thinking about the ways we transmit LGBTQ+ culture. Very few LGBTQ+ people learn our history in schools or at home, so that is where our art has always stepped in. I’ve since been focusing my research on artists, writers, etc. producing work with that cultural transmission in mind. I have no idea where this research is headed as I’m still in the early exploratory phase. I’m also involved in the William & Mary LGBTIQ Research Project, a Richmond and Williamsburg area project to document the area’s queer past, and LGBTIQ Virginia, a coalition of LGBTIQ projects across the commonwealth.

Jerry Watkins holds a PhD from King’s College London in American studies. He is a historian of sexuality whose work has focused on the queer South. He continues to research, write, and work with community history projects that seek to diversify the archive. His teaching focuses on the twentieth-century United States, social justice, the modern South, and the history of sexuality.

Jerry Watkins holds a PhD from King’s College London in American studies. He is a historian of sexuality whose work has focused on the queer South. He continues to research, write, and work with community history projects that seek to diversify the archive. His teaching focuses on the twentieth-century United States, social justice, the modern South, and the history of sexuality.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com