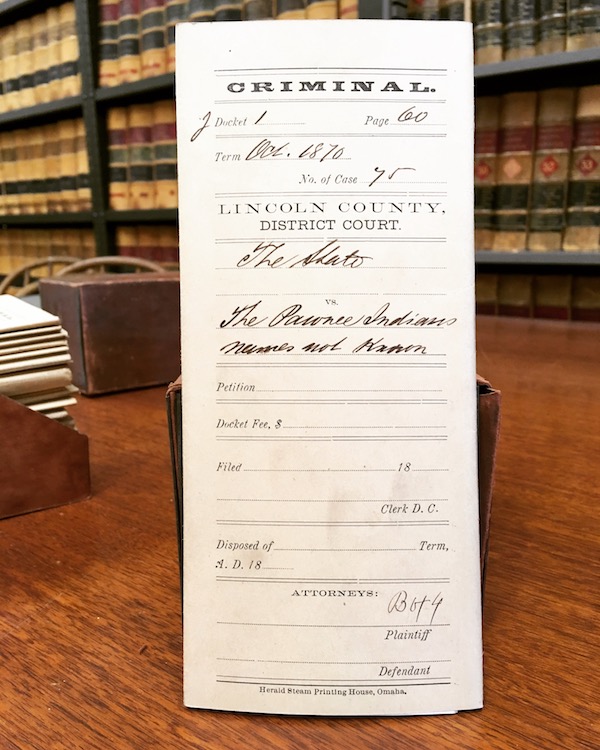

In October 1870, authorities arrested three men of the Pawnee tribe in unorganized territory west of Lincoln County, Nebraska. These men were charged with “committing buggery” upon another male, probably a young boy. Prior to standing trial, the court gave them Anglo names: Caesar, Columbus, and George Washington. At the jury trial, Caesar and Columbus were convicted of sodomy and both were sentenced to one-year terms in the Nebraska State Penitentiary. After the trial, the case file was boxed away, somehow survived the courthouse fire of 1923, and now resides in the rooftop storage shed of the Lincoln County Courthouse in North Platte.

While the case of Caesar and Columbus is itself exceptional, the process of finding and reading this case was, in fact, very similar to locating other sex crimes in rural Nebraska. In the summer of 2017, I spent eight weeks searching for and documenting cases of rape, incest, and sodomy in twenty courthouses across the state. While these trips served as a crash course in reading legal records, they also raised important questions about how to conduct research on sexual violence in rural spaces. As historians, where do we locate these sources? How do we gain access to them? And what information can they reveal?

Finding cases of sexual violence is often a difficult starting point, particularly for rural areas. With the increased digitization of source materials, however, this process is becoming a bit easier. Using the Prisoner Index Database provided by the Nebraska State Historical Society (NSHS), I was able to compile an initial list of sex crime prosecutions. Wanting not just cases that resulted in conviction, however, I turned to newspapers.com and Chronicling America. By conducting keyword searches in Nebraska newspapers for generic terms—rape, incest, and sodomy—as well variations of more coded language—criminal assault, carnal knowledge, debauched, outraged, ravished, etc.—I was able to assemble a more complete list of cases spread across urban and rural areas.

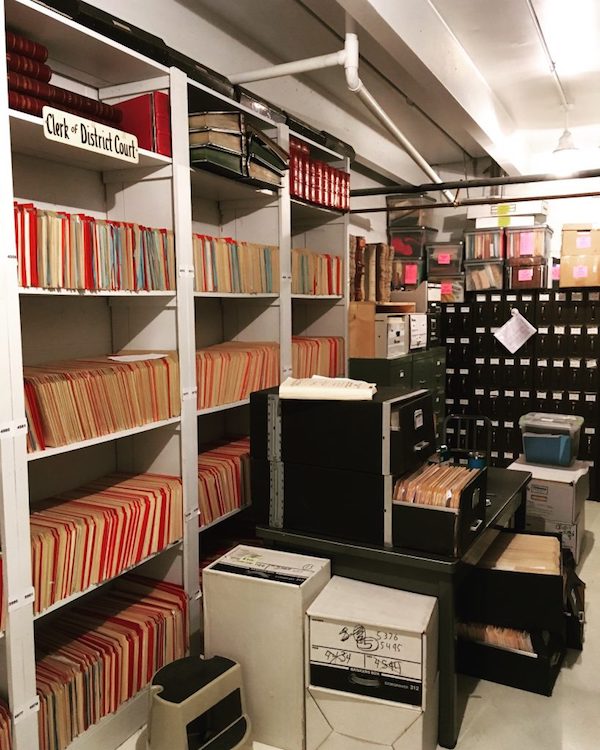

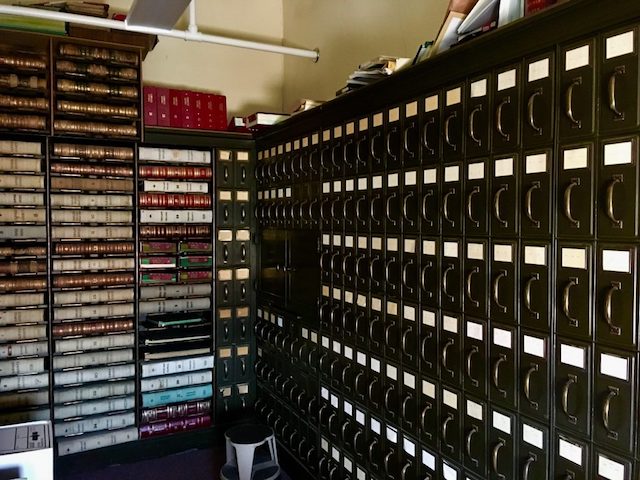

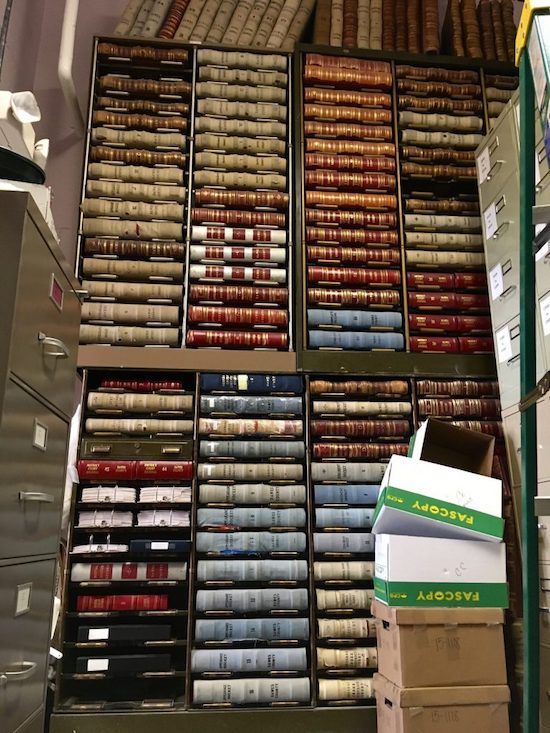

Rape, incest, and sodomy were felony charges, so these trials were prosecuted at the district court level. While the Government Records Division of the NSHS holds the district court records for several counties, the records for most of Nebraska’s 93 district courts remain in local courthouses. Because of the geographic dispersal of these records, I realized it would be necessary to travel from county to county to find cases on my list. The process of gaining access to these records, then, became somewhat more intimidating than research in a traditional archive.

While most archives are run by a head archivist, the records of the district court come under control of the Clerk of the District Court of each respective county. Unlike traditional archivists, clerks serve in an elected position. Being from Nebraska and aware of the conservative nature of state and local politics, I was unsure how my research topic would be received. These materials were public records, of course, but would I still be able to access them if my project was viewed as unsavory? In my emails to clerks while planning my trips, I was very guarded in describing my project. Emphasizing my personal connection to the state and my academic credentials, I also de-emphasized the more controversial aspects of my research, writing that I was interested in “violent and moral crimes” rather than “sex crimes.”

Once I began my research trips, however, I realized that the wariness and discomfort I had anticipated were largely unfounded. The clerks I met were not only incredibly accommodating, but most were also fascinated by my research and eager to learn about what I was finding. In a follow-up email with one of the clerks thanking her for letting me come and research, she said most clerks in rural areas were just “glad to see our constant recording means something to someone.” This eagerness to have researchers come in allowed me to build a good rapport with many of the clerks, and many of them gave me an independence and free rein of the vault not normally found in traditional archives.

Because many rural counties did not catalogue their criminal cases by crime, my previous digital research was indispensable. While the records I found often provided only basic information, other case files were much more extensive, including court testimony, affidavits, handwritten confessions, bills of exception, and sentencing hearings. Some of these materials were kept due to “accidental archiving” by previous clerks who had filed away materials that, while related to the case, were not necessarily part of the official record. All these materials, though, provided a wealth of information not only about the trial process, but also how rural communities and local courts reacted to sexual violence.

My trips through rural Nebraska, however, were not only important for the information I recovered, but also for the connection they reinforced between me and my research. There is something to be said about reading a case file in the courthouse where the trial occurred; it provides a connection to the past and to the people involved in the case. On my last trip, in a county in southeastern Nebraska, an example of accidental archiving drove this connection home. While searching for a bill of exceptions from a 1970s rape case, I stumbled on physical evidence from the trial, preserved in clear plastics bags. While a shocking discovery—and the only time I have cried in an archive—these stained pieces of clothing were an important reminder of the human connection in the stories we tell. As historians, it can become easy to distance ourselves from our subjects, to analyze from a space of removal. As historians of sexual violence, regardless of whether we study rural or urban spaces, we need to be reminded not to lose sight of the fact that we are studying real people with very real experiences.

Brian Trump is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Kansas, researching the intersections of gender/sexuality, space, and state power in the 19th and 20th century United States. His dissertation explores the history of sex crime prosecution in Nebraska between 1880 and 1980.

Brian Trump is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Kansas, researching the intersections of gender/sexuality, space, and state power in the 19th and 20th century United States. His dissertation explores the history of sex crime prosecution in Nebraska between 1880 and 1980.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com