Emily Lobenstein

In 1989, well-known Playboy photographer Scott Cohen traveled through the Iron Curtain and photographed, with the assistance of Soviet photographer Alexander Borodulin, almost forty Russian women for a special Playboy edition on the Soviet Union. While Playboy photographers previously photographed women across the Eastern Bloc, this edition was the first to get Russian Soviet women nude between its pages. Entitled “The women of Russia: they are – you guessed it – red-hot,” the article utilized images of Lenin, St. Basil’s Cathedral, and Red Army soldiers as props alongside Russian women to paint a picture of feminine longing for both American men and the American way of life, namely capitalism and consumerism. This controversial edition of Playboy is often overlooked by scholars of the perestroika, the period of reform in the Soviet Union during the 1980s, but it reveals a narrative important to political and diplomatic histories of the Soviet Union and the United States. The spread illustrates both the persistent tension between these two super powers even in an era of increasing military and political cooperation – most notably arms de-escalation treaties with two American presidents in 1987 and 1991. It also highlights changes in the Soviet regime under Mikhail Gorbachev that colored the way the regime did and could respond to the pornographic spread.

The Playboy issue stirred up discussions about gender and dominance between the Soviet Union and the United States roiling in public view since the Kitchen Debates in 1959. Many of the interior shots included portraits of Lenin, the ubiquitous newspaper Pravda, and Red Army soldiers, both living and on posters. Cohen also staged shots in front of famous Soviet and Russian landmarks. In one such shot, Olga Egorova – a runner-up crowned Miss Discovery in the 1988 Miss Moscow pageant – posed in a group shot wearing a tight, sheer dress in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral. In another, hair stylist Sveta Nikolaeva posed almost entirely nude in Sochi’s Pushkin fountain. In addition, Cohen mocked the Soviet pageant phenomenon. Several of the women who posed for him were beauty queens, though none as prominent as Miss Moscow 1990’s Larisa Litichevskaya, and Playboy’s editors put a photograph of Litichevskaya’s crowning prominently in the spread.

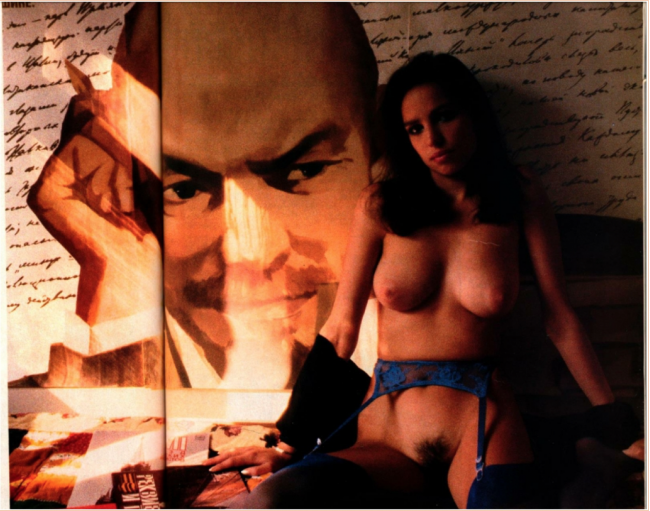

The Playboy spread also mocked Soviet sovereignty. Cohen portrayed Soviet women as natural resources who were, thanks to perestroika, up for grabs by American men. The explicit sexuality, colonial tone, and use of nearly sacred Soviet imagery aside, the quotes collected from the women photographed painted a picture of American ideological dominance in the minds of Soviet women. Some were merely sexual or humorous in nature, but many framed both American culture and American men as aspirational and superior. When asked what she preferred sexually, typist Vanda Rudneva replied, “I like attentive guys and dislike losers.” While this response does not, in and of itself, degrade Soviet men, its positioning alongside material that explicitly implied American male sexual dominance is significant. Asked about her thoughts specifically on American men, gymnast Tat’yana Kaftunova replied, “I love them to terror.” Cohen interjected that she likely meant “to death.” Kaftunova’s preference for American men set a tone of American sexual dominance. The editors at Playboy took this subtle emasculation further. Using a partially nude Marina Kozhuchova as a size comparison, they poked fun at Lenin, whom they called “the father of the Soviet state,” for his short stature. Other quotes alluded to political and economic discontent. Playboy consistently posited the triumph of the American capitalist system over the Soviet communist one. Many of the women profiled in the spread expressed dissatisfaction with their lives in the Soviet Union. Vera Esina, aged 20, told Cohen that her dream was to “get a taste of the good life in the United States.” The implication was, of course, that the good life was not to be had in the Soviet Union. Cohen posed Moscow bookkeeper Lena Nosova nude on a bed in front a large, angry-looking portrait of Lenin. He wrote, “Lena’s real dream is to work abroad, a plan that doesn’t seem to please the comrade [referring to the portrait of Lenin in the background] on the wall. Do-svidanya.”

This expression of American cultural dominance hit a nerve with Soviet elite. The beauty queen profiled in the article, Larisa Litichevskaya, was nearly stripped of her title and prevented from traveling abroad as Soviet officials scrambled to preserve her image. However, the contours of Soviet power under Gorbachev had changed radically and despite general uproar, Playboy hosted a release party for the edition in Moscow just a year later.

Depictions of women can serve as a litmus test for the cultural values of a country. When these depictions change, or are mocked or used by other countries, historians should take note. The Soviet edition of Playboy is, for many historians of late Soviet culture and American-Soviet interactions, an amusing footnote. In reality, it had the power to reveal deep-seated tensions and enormous cultural and political change. These images are a good reminder that pornography continues to be a rich source base from which to understand history.

Emily Lobenstein is a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Her research centers around late and post-Soviet sexualities as they were formed and presented in the media. She is also interested in the global networks of ideas and images that transcended the Iron Curtain.

Emily Lobenstein is a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Her research centers around late and post-Soviet sexualities as they were formed and presented in the media. She is also interested in the global networks of ideas and images that transcended the Iron Curtain.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com