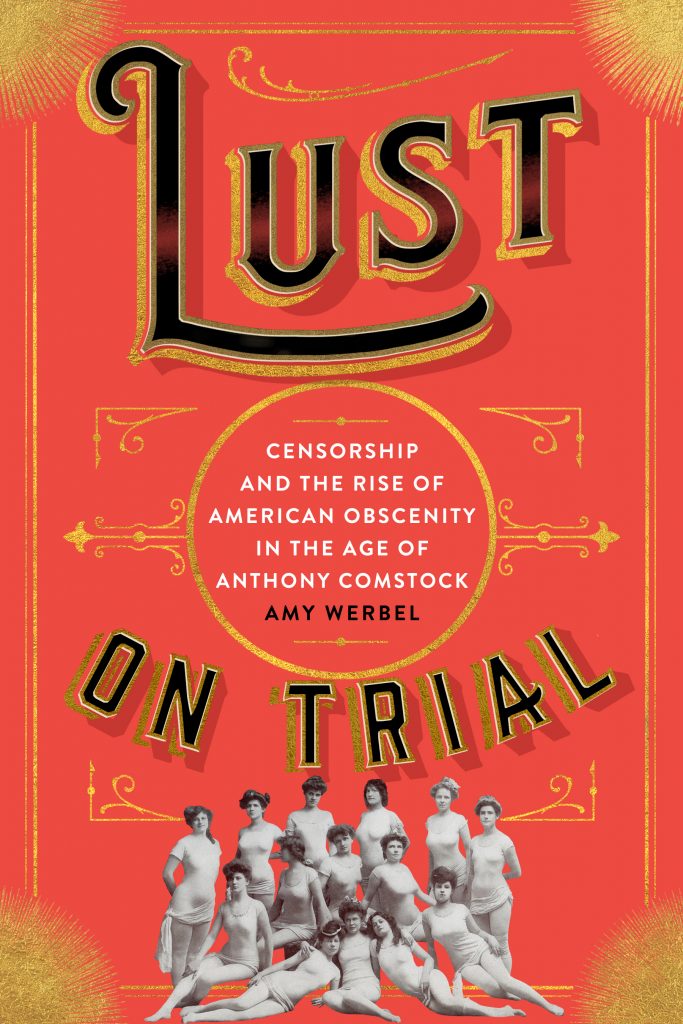

Lust on Trial takes readers on a journey through America’s sexual underbelly as viewed through the eyes of Anthony Comstock, the nation’s first professional censor (1844-1915). Descriptions and illustrations of materials deemed obscene make it possible to assess sexuality at the time with new insight, particularly expressions and behaviors emerging into public discourse including dominant women, submissive men, homosexuality, voyeurism, and exhibitionism.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions do you still have?

Werbel: In the course of writing my first book, Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia, I came across Comstock’s name. Artists and art educators who wanted to introduce more study of the nude in art schools in the late nineteenth century, and also exhibit more paintings of nudes, were worried about Comstock showing up to shut them down. I really didn’t have any idea who he was, and when I started to read more, I realized there was a big story there that hadn’t been told. The questions I am still chewing on involve the legacies of this history in the post-Comstock era.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? What sources did you use, and were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges?

Werbel: Comstock kept meticulous records of the materials he seized and destroyed in huge “Records of Arrest” blotters that are now in the Library of Congress. I spent two weeks there going through them, and made an excel spreadsheet listing everything that constituted some kind of visual culture – including paintings in brothels, sex toys, girly photographs used to advertise cigarettes, and some things I had to spend time figuring out. I sent a pretty funny email to a lot of archivists, something like: “I would be enormously grateful if you could let me know if you have any of the following in your collection: “vile Valentines, obscene cigar holders, a glass penis filled with liquor, an obscene hen and rooster jar that forms an indecent posture, etc.” Almost all of this stuff survived in the Kinsey Institute Collection, including some things I didn’t have room to illustrate, for example “sooner” dogs that you could fill with “eggs” and then watch them defecate. Comstock destroyed hundreds of them – he had no sense of humor.

For obscene prints and illustrated books, the American Antiquarian Society has a great collection. Over the years, they clearly had collectors interested in saving what were euphemistically called “gentlemen’s libraries.” My most exciting discovery was the Case Files of Post Office Department Inspectors in the National Archives and Records Administration, because many of these contained examples of the evidence seized in obscenity raids, which Inspectors including Comstock sent to their supervisors in D.C. to prove they were on the job.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Werbel: If I had more space, money, etc., I definitely would have illustrated even more examples of evidence, and included more discussion of fascinating cases that are not already published. For example, Comstock spent a lot of time getting into the thick of family disputes. Parents sometimes turned to him for help with a child (typically a girl) who ran off to watch “low plays,” drink in saloons, etc. His typical version of “helping” was to have these girls deposited in prison. If I had more time, I would have liked to search for evidence of what happened to those girls and their families.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Werbel: Lust on Trial is extremely inter-disciplinary, so it could be used in a lot of different courses involving gender and sexuality studies. When I discuss my work with students, I am most interested to hear what shocks them (or more often what doesn’t shock them) from the past. They tend to bring in their own comparisons from contemporary popular culture, gender politics, efforts at censorship, etc.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Werbel: We are, at our best, a nation governed by secular rule of law. Lust on Trial tells the story of a time when this went off the rails in the worst possible way. Americans didn’t take repression lying down, just like they aren’t doing so today. This really is an inspirational story about the power of “We the People” to stand up for pluralism, shared power, acceptance of sexual difference, and the incontrovertible right of women to control their own bodies without interference from the state. There are a lot of heroes in the fight for civil liberties in my book whose stories haven’t been told before – artists, photographers, defense attorneys, and entrepreneurs. I also hope the book can be a wake up call to people who want to emulate Comstock. If anyone could have made America a Christian nation through censorship and suppression of birth control and abortion, it was Anthony Comstock. The ultimate futility of his life’s efforts is a pretty bracing cautionary tale.

The images and texts I unearthed effectively demonstrate an enduring lesson about the effects of censorship campaigns in the United States: While it is certainly possible to temporarily ‘cleanse’ the public sphere, doing so provokes more resistance than compliance, thus resulting in short-lived, Pyrrhic victories.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Werbel: In addition to promoting Lust on Trial, I am currently in the process of shaping proposals and seeking funding for two new research projects. More on those to come . . .

Amy Werbel is a graduate of Harvard College and Yale University, and the recipient of fellowships from numerous institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her previous publications include Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Yale University Press, 2007) and Lessons from China: America in the Hearts and Minds of the World’s Most Important Rising Generation (self-published, 2013). Werbel presently serves as Associate Professor of the History of Art at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

Amy Werbel is a graduate of Harvard College and Yale University, and the recipient of fellowships from numerous institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her previous publications include Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Yale University Press, 2007) and Lessons from China: America in the Hearts and Minds of the World’s Most Important Rising Generation (self-published, 2013). Werbel presently serves as Associate Professor of the History of Art at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Bravo!