Anne Balay

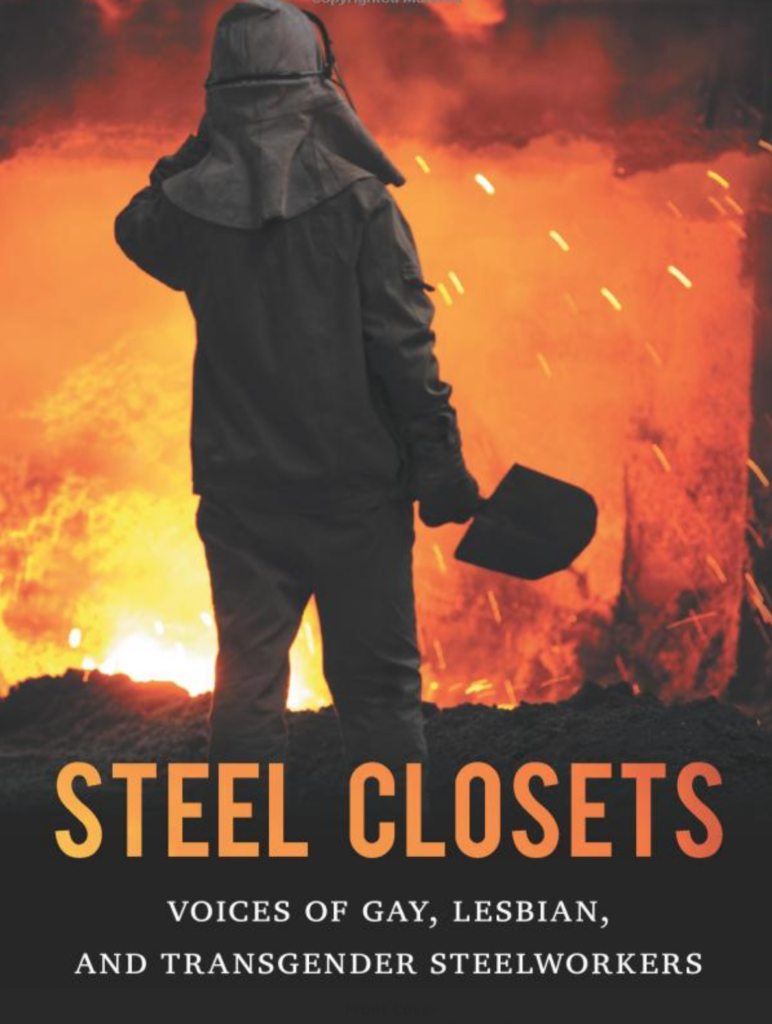

Queer working-class people are substantially invisible. My goal for Steel Closets was to document what life and work meant to one group of these workers, as they experienced the gay rights movement and rapid deindustrialization simultaneously. Their stories are important in and of themselves, but they also shift understandings of what queerness is, and how it is shaped by class, geography, and race.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic?

Anne Balay: I taught (at the time) in Gary, Indiana, and I was fascinated by the huge steel mills that lined Lake Michigan. There were security gates, so I couldn’t get close, but I would study the methane flames from the high chimneys, and time the shift changes, and gradually my curiosity about what it was like to be queer in there grew.

NOTCHES: This book is clearly about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

AB: Queer working-class life at work. Much of the existing scholarship about queer pasts emphasizes social spaces and bar life. I wanted to study what work was like, and how it shaped queer behavior, and queer belonging.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use, were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

AB: I had almost no luck with archival research. Though I visited several archives, including Rivers of Steel in Homestead, PA, none mentioned gay steelworkers at all. Each gave me a sense of the work setting in general, its changes through time, and management and labor issues. But for queer stories, I turned to oral history.

Ultimately, I did oral histories with 40 LGBT steelworkers. It was very hard to find these narrators, because queer steelworkers are very cautious. For their own protection they remain closeted at work so they were reluctant to talk to me or to sign my detailed consent form (required by my university at that time). I would frequent local gay bars, and steelworker bars, and get familiar with the culture. That helped. And I had worked as a car mechanic for many years, so I could follow conversations about tools, dirt, danger, heat, etc. Almost no narrators could lead me to any others. They each thought they were absolutely alone in the mills. And that loneliness made many very willing to talk, once they got started. To tell their stories became a palpable relief.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

AB: I learned that many men have sex with other men at work. These men identify as straight, they are just working with what is available at the time. I talked to many gay-identified men who had frequent sex with them, but I couldn’t find a way to talk to straight men who did. That wasn’t something they would admit to, or describe.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

AB: Lord yes. I had no idea how to do oral history interviews, how to code, or how to structure a book-length work. And I had received ideas about what gay and lesbian people were, and how we acted. Those were all challenged. I came to understand that if scholars look for what we think of as gay people, we’ll miss many of the queer pleasures and possibilities that exist. Also, I imagined that blue-collar workers would be racist and homophobic. That was sometimes true. Yet I also found more humor, and more acceptance in these communities than I found in academic spaces. The contradictions were confusing, but worth understanding. Blue-collar work space in general is accepting and hands-off. If you do the work, and are fun to work with, they are much less hostile to queers than many apparently liberal work worlds. At the same time, the exceptions are more violent.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

AB: It remains difficult to think about sexuality/gender and class at the same time. Persistently difficult. My book, by including detailed, particular stories situated within geographical and historical context, provides a means to do so. So I teach it in that context, as a challenging aspect of intersectionality. It works well with Marlon Bailey’s Butch Queens Up In Pumps, because that book interrogates the definitions of work. Bailey gets readers thinking about alternate forms of work that are not labor for pay, but are community sustaining. That’s another crucial way to think both sexuality and work and their overlaps.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

AB: LGBT activism needs reorientation. As a group, we need to understand that the lives of queers are not improving unless the lives of ALL queers are improving. Marriage brought gains to only a segment of queer folks, and harm to many others (who had no workplace protections, so couldn’t risk getting married, and yet faced backlash instigated by the cultural shift it signaled). The way to know what other queers need/want is to ask them; to take time to understand what queerness means to them, and how it fits within their lives.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

AB: Steel Closets was published in 2014. Then I learned how to drive an 18-wheeler, and did so briefly, then doing oral histories of 66 queer, trans, and black truck drivers. The new book is called Semi Queer.

Anne Balay graduated with a PhD from the University of Chicago, after which she promptly became a car mechanic. Though in subsequent years she returned to academia as a professor both at the University of Illinois and Indiana University Northwest, she never lost her interest in blue collar work environments. Dr. Balay moved to Gary, Indiana to teach, and was immediately interested in the steel industry of the region. Her coworker and mentor, Jimbo Lane, suggested that she would be perfectly suited to meeting with and writing about the LGBT workers within the mill community, and Steel Closets was born. Anne then attended commercial truck driving school, got her CDL, and drove over the road. Oral histories of truck drivers she did in 2015/16 have led to her new book Semi Queer. Anne is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Haverford College.

Anne Balay graduated with a PhD from the University of Chicago, after which she promptly became a car mechanic. Though in subsequent years she returned to academia as a professor both at the University of Illinois and Indiana University Northwest, she never lost her interest in blue collar work environments. Dr. Balay moved to Gary, Indiana to teach, and was immediately interested in the steel industry of the region. Her coworker and mentor, Jimbo Lane, suggested that she would be perfectly suited to meeting with and writing about the LGBT workers within the mill community, and Steel Closets was born. Anne then attended commercial truck driving school, got her CDL, and drove over the road. Oral histories of truck drivers she did in 2015/16 have led to her new book Semi Queer. Anne is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Haverford College.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Steel Closets is an excellent contribution to our histories and we need much more like it – looking forward to reading Semi Queer.