Emma Maggie Solberg

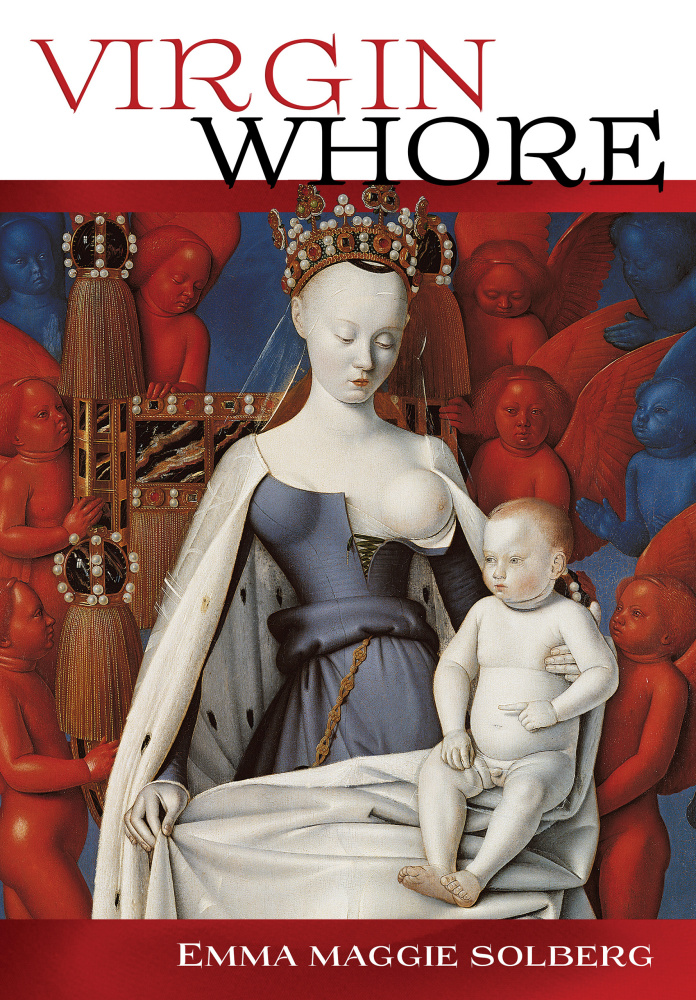

In Virgin Whore, Emma Maggie Solberg uncovers a surprisingly prevalent theme in late English medieval literature and culture: the celebration of the Virgin Mary’s sexuality. Although history is narrated as a progressive loss of innocence, the Madonna has grown purer with each passing century. Looking to a period before the idea of her purity and virginity had ossified, Solberg uncovers depictions and interpretations of Mary, discernible in jokes and insults, icons and rituals, prayers and revelations, allegories and typologies—and in late medieval vernacular biblical drama. By revealing the presence of this promiscuous Virgin in early English drama and late medieval literature and culture, Solberg provides a new understanding of Marian traditions.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is the book about? Why will people want to read this book?

Solberg: Virgin Whore charts the long history of the many dirty jokes that have been told about the Virgin Mary from the earliest days of Christianity to the turn of the new millennium focusing in particular on the late medieval period, reading these jokes not only as insults (as they have tended to be taken) but also as devotional compliments. This book offers readers a sex-positive interpretation of the version of the Virgin Mary who was venerated by artists, saints, and sinners in the late Middle Ages—a version of the Virgin who, I hope, will seem both familiar and strange to readers today.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions do you still have?

Solberg: Feminist scholars who work on the past are trained to look for histories that have been erased, neglected, or misunderstood. That’s what drew me to this topic—the opportunity to restore such an important half-forgotten cultural memory. That, and the medieval Virgin Mary’s sense of humor. Contrary to what you might expect, the medieval Madonna is a lot of fun. She wrestles with demons, seduces angels and deities, and rescues sinners from certain damnation just in the nick of time—very much like a medieval superhero, because this is exactly what she was. I still have so many questions about the Virgin Mary of the late Middle Ages—but the one that I’ve been grappling with recently is the question of the medieval Madonna’s blackness. You may have heard of “the black Madonna,” by which we tend to mean a devotional image (a statue, painting, altarpiece, icon) of the Virgin Mary who seems to have dark skin. Seems to whom? Across the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when English Lollards, reformers, and iconoclasts mocked Catholic images (or, as they had it, idols) of the Madonna, they called them—in the same breath— whorish and black. Should we take this kind of statement figuratively or literally? If we’re going with a literal reading, then are we to understand that these statues are black because of black wood, black paint, black soot, or some combination thereof? What are we to make of this?

NOTCHES: This book speaks to histories of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it highlight?

Solberg: This is also a book about the intertwined histories of Christianity and comedy. We tend to think of Christianity and comedy as mutually exclusive categories, or at least as a bad match—but I argue that the two fit together snugly, not only in content (in that Christianity, as Dante suggested, is itself a comedy—a divine joke with a happy ending) but also in form. Comedy, as Aristotle and Horace taught, is low and ugly, and tragedy noble and sublime. Christianity upended this hierarchy, choosing the despised style of comedy to express its mystery. Jesus communicated his good news in the flesh and the vernacular, telling folksy parables about seeds, sheep, and taxes to children, lepers, and prostitutes. In this sense, the sacred and yet also obscene farces that I study make perfect theological sense, even if Christian farce is a genre with which we’re no longer really familiar. We still tell dirty jokes about the Virgin Mary (witness a lot of stand-up comedy, the odd banned episode of South Park, Monty Python’s Life of Brian), but rarely (if ever) in a devotional context.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Solberg: Once you get tuned into the legacy of the Madonna, you begin to find her everywhere. Recently, I’ve been noticing how embedded Mariology is in our day-to-day language. The word “marionette,” for example, means “Little Mary.” Why? Very little research has been done on this question, but I’ve found tantalizing and uncited claims that the phrase refers to the mechanized statues of the Virgin Mary that enlivened late medieval and early modern tableaus. Just the other day, I realized that the word “lady bug” (or “ladybird beetle”) refers to the Virgin Mary—some quick research revealed that the seven black spots on its red shell were associated with the Seven Joys and Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. In class this morning, one of my students reminded me that the interjection “Marry” that peppers Shakespearean speech means “Mary,” as in the Mother of God. The ubiquity of the Madonna in our language and culture is overwhelming.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

Solberg: Absolutely. This project began as a study of virginity in the early modern period and then became the study of the Virgin in the medieval period. The project’s first seed was planted in a seminar that I took in graduate school at the University of Virginia with Professor Katharine Maus on English Renaissance drama. We read Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess, which may well be the most outrageously pro-virginity text that I’ve ever come across. I found this play’s deranged and bloody obsession with virginity strangely fascinating, and it sent me off on a research project about, among other things, “greensickness,” an early modern disease (in which we no longer really believe—like hysteria) that afflicted teenage virgins. I quickly got lost in the vast topic of pre-modern virginity. My dissertation director, Bruce Holsinger, saved the day by telling me to find my way by beginning with a close reading, which is great advice that I continue to pass along to my students today. I turned to the first text on my reading list, the late medieval N-Town Plays (an East Anglian theatrical compilation focused on the life of the Virgin Mary) and basically never left that one manuscript.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

Solberg: I have always been interested in differences and similarities across time when it comes to sexuality. The American public education system exposes us to Shakespeare early, and I remember dwelling on the puzzling sexuality of his characters. Like, what in the world is going on with these people in Twelfth Night? It’s always, for me, the same process when studying textual evidence of the history of sexuality from the deep past: At first, you notice something strange and alien in an old text, an idea that seems impenetrably weird and antique; slowly, you read deeply and widely in texts from the period, struggling to figure out the systemic logic of the unfamiliar idea; finally, after ruminating on the idea for ages, you suddenly see it where you least expected—right in front of you, today, in the twenty-first century. It’s only then that you realize you knew the idea well all along, that you had been hearing it all your life. We tell ourselves a lot of lies about the present moment—about how much progress we’ve made, about how it’s better than it’s ever been. Like Candide, we have been told that this is the best of all possible worlds. Presentism is blinding. The past is so much more honest than the present.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book, and were there any especially exciting discoveries?

Solberg: I did not set out to discover new evidence, but rather to re-interpret what we already know. My discoveries were never of new-found land, but rather of half-forgotten memories. Take the image of the Madonna and Child, for example. This is iconography with which we are all familiar. But this project made me see the Madonna and Child differently. I hadn’t really ever thought before about the comedy of this iconography. I was first clued in by Reformation polemic written against the image of the Madonna and Child, in which iconoclasts ranted and raved about how offensive they found the representation of Jesus as a breastfeeding baby. He’s a grown man, they write—he’s not a baby! He’s thirty-three years old! What’s he doing at his mother’s breast? (See, for example, William Crashaw’s The Jesuit’s Gospel, which you can find on Early English Books Online.) Their rage alerted me to the presence of a thread of discourse in late medieval theology, iconography, and literature that suggested the notion that Mary seduced God, bewitched him, and metamorphosed him into a helpless baby in order to save mankind—because God wasn’t going to do it until Mary tricked him into it. (For a particularly explicit articulation of this idea, see Bernardino of Siena’s sermon De superadmirabili gratia et gloria Matris Dei, which you can find in the edition of his complete works published by Quaracchi.) In this light, the image of the Madonna and Child takes on a whole other meaning. It becomes an image of the total triumph of Mary over God.

NOTCHES: How do you see this book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Solberg: It is my hope that this book would help students see the Madonna of the Middle Ages (and the Madonna more broadly) in a new light. As for what I would assign with it—I would say that students should read this book with the medieval plays about which it is written, but these texts are in Middle English, which puts up a barrier. However, if your students are up to the challenge, the Medieval Institute Publications at Western Michigan University publishes open-access editions of classroom texts for TEAMS (the Consortium for the Teaching of the Middle Ages), and you can find the N-Town Plays, edited by Douglas Sugano, online through the Robbins Library Digital Project. I highly recommend the Nativity play, which features an onstage post-partum gynecological examination of the Virgin Mary.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Solberg: It wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say that the Virgin Mary is the most famous woman in world history. Her history provides an invaluable archive for feminist scholars—one that stretches across centuries and cuts across divisions of class, race, and gender. Her history has may meanings, and belongs to everyone. I am not a Christian and I was not raised Christian, but I grew up inundated by the iconography of the Madonna, as do we all.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Solberg: At the moment, I’m working on a study of bookworms in medieval manuscripts—literal bookworms, as in insects. We’ve learned so much in recent years about the DNA of the ruminants (cows, goats, sheep) whose skins make up the leaves of medieval manuscripts, but we have yet to hear much from the bookworm. Small wonder: the cow gives its skin for the conservation of words, while the bookworm, the natural enemy of the librarian, steals our words. In this study, I am trying to reconsider the ancient rivalry between human and insect bookworms as a partnership, and even as a co-authorship of the text.

Emma Maggie Solberg is Assistant Professor of English at Bowdoin College, where she teaches British medieval literature and culture, from Beowulf to Skelton. Her research interests include early English drama and the cult of the Virgin Mary. Virgin Whore (Cornell University Press, 2018) is her first book.

Emma Maggie Solberg is Assistant Professor of English at Bowdoin College, where she teaches British medieval literature and culture, from Beowulf to Skelton. Her research interests include early English drama and the cult of the Virgin Mary. Virgin Whore (Cornell University Press, 2018) is her first book.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Hello,

I’ve heard of why ladybugs (or Our Lady’s Bugs) are associated with Mary. At some place and time in english speaking history there were insects (not lady bugs) that were eating crops; people prayed to Mary to remove the insects. According to this legend, Mary sent lady bugs to eat the crop eating insects. Thus, Our Lady’s Bugs… Ladybugs.

After the fact, I think people have drawn parallels between lady bugs and our lady… the seven sorrows and the fact that ladybugs have a veil/mantle thing going on with their shell/wing combo.