Lisa L. Wynn

Set in transnational Cairo over a two-decade period, Love, Sex, and Desire in Modern Egypt: Navigating the Margins of Respectability is an ethnography about love and desire, romance and sex, female respectability and male honour, and Western theories and fantasies about Arab society. The book uses stories of love affairs to ask how well classic anthropological theories – kinship, gift theory, mimesis – apply to unconventional subject material.

NOTCHES: Why will people want to read your book?

Wynn: I think people will want to read it for the stories! The book revolves around a few key characters and their love affairs: there’s Sara, a working-class woman who has an affair with a married man and becomes pregnant, only to be abandoned by him. There’s Aya and Zeid, an engaged middle-class couple who are constantly arguing about things like whether Aya’s friend is a prostitute or a virgin. There’s Malak, a European belly dancer who keeps falling in and out of love. She doesn’t mind it if someone nice wants to pay her for sex, but mainly she wants to be loved by a man who will treat her with respect and won’t treat her like a whore just because she’s a dancer. And there’s Alia, a Christian banker who left her abusive husband and now is the mistress of a wealthy Muslim man, Haroun, who greases the wheels of business by hosting risqué parties for other men and their mistresses.

The book has a pretty unconventional structure. It alternates between chapters that just tell stories about people’s intimate lives, and chapters that delve into anthropological theory. The stories really suck you in, and then they make you wonder, “What does this have to do with gift theory?” Or at least I hope that’s what they do!

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions do you still have?

Wynn: It’s a kind of cliche of the discipline for anthropologists to go into the field looking for one thing and then end up writing about something else entirely. In my case, I went to Egypt to study tourism, and I did end up writing my first book about that, but I also paid attention to the things that people wanted to talk about when I wasn’t the one asking questions. And what they wanted to talk about was love and desire and sex and relationships.

NOTCHES: This book includes the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Wynn: Sex, and rumours about who is having sex, definitely features in the book, but more than sex, it’s about love. It’s about people trying to figure out what love is, what they want, and what is the relationship between sex and love. But it’s also about people grappling with society’s gaze and judgment, and trying to figure out how to claim the label “respectable” while pursuing their own paths of love and desire. More broadly, it’s about political economy, and how those structures of the state shape the kinds of intimacies and justice that are available to individuals. And even more broadly, it’s about a history of the way Western researchers like me have represented sex and sexuality in the Middle East, and about the effects of those representations.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book?

Wynn: I lived in Cairo for nearly three and a half years in total while I was doing my dissertation research on tourism in Egypt. This book actually represents all the interesting things I was learning from people outside of that research topic. Anthropologists sometimes call our method of participant observation “deep hanging out” — just spending time with people and seeing what their lives are really like and what matters to them. What I found out is that people wanted to talk about their love lives.

The biggest discovery was also my biggest challenge. I had a good friend and informant, and I’d hired her as my research assistant for a project I was doing. One evening, we were sitting around in a hotel room, talking about the interview questions, testing them and refining them. We were also watching a soap opera on the TV. It was pretty relaxed. All of a sudden, she told me this awful story about being raped a few years previously. I’d known her at the time but it took years before she decided to tell me. I was shocked. I felt so awful for everything she’d gone through, and I was so angry, too. And then I didn’t know what to do with her story. She knew I was working on this book and she wanted me to tell her story, but I wasn’t sure if I should. I kept asking myself, if I’m writing a book about sex and love and desire, should I also write about sexual violence? Or would I just be contributing to the whole history of problematic representations of the Middle East as full of violent men? I grappled with that a long time. But my friend was insistent that I should tell her whole story, the good and the bad, and I eventually realised that I had to, because it mattered to understanding why some women work so hard to protect their social respectability, and that was a core theme of the book.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Wynn: There were lots of stories that I left out! I had too many good stories and I just couldn’t include them all. I think if I could have included one more story, it would have been a story about a woman who became the second wife of an already-married man. The dominant Western narrative about polygamy is that it exploits women. But this friend of mine was an incredibly successful single woman. Like, she was literally a star. She was beautiful, and she was wealthy, and she could have married anyone, but she got all the way to her 40s without ever marrying, even though she had lots of suitors. And then she met this guy who was already married and she decided, “I want him.” She pursued him, and she married him, knowing he already had another wife. And then after a few years, the marriage fell apart, but before she divorced him, she adopted a child who she’s now raising as a single mom. She was so unconventional in so many respects, and those are the stories I love to tell: people who carve out their own path in society and do what you wouldn’t expect.

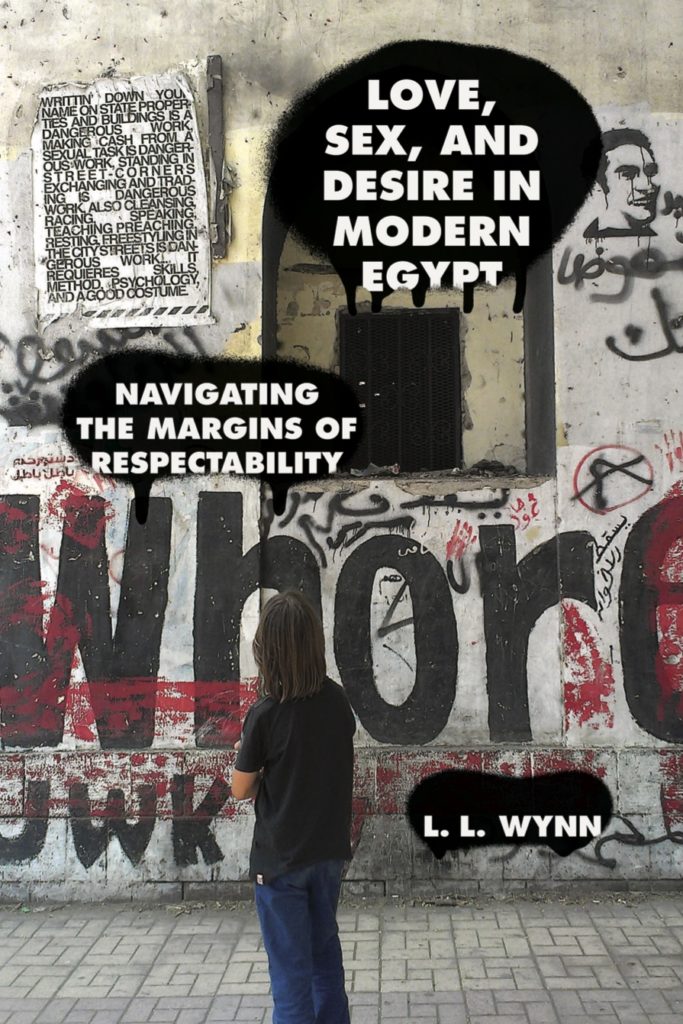

One other thing I wish I’d included is some description of the book’s cover image. It’s a striking image, but there’s no context because book covers get designed long after the book manuscript is complete. It’s a picture I took of one of my children looking at graffiti in Cairo’s Tahrir Square after the 2011 Egyptian revolution. Some amazing Egyptian artists and activists keep putting up this powerful street art that comments on social and political issues, and if you look closely at the English words pasted on the wall in the top left of the image, you’ll see what I mean.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

Wynn: From the start, I wanted to structure this book as alternating chapters of story and theory, and I wanted to start with a story. I wanted to send the message that these people’s stories matter in and of themselves. Theory can help us to understand the ethnographic material, but I didn’t want people’s lives to just be anecdotes that illustrate some theoretical point; I wanted them to stand alone first, so that later we could see how their stories illuminate academic theories. Other academics kept telling me, “Don’t do that. Do something more conventional. Merge the stories and the theory. Bring them together in each chapter. This doesn’t look like a proper academic book.” But I stuck with my guns. Mostly. There are a handful of citations in that first chapter, but mostly it tells stories. It’s true it doesn’t totally look like a proper academic book, but it’s much more readable.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality? Why does this history matter today?

Wynn: For this book, I was trying to understand how it fit into the history of Western representations of sexuality in the Middle East. There is indeed a long history of this. The Syrian-British writer Rana Kabbani wrote a book called Europe’s Myths of Orient: Devise and Rule in which she used the lens of Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism to show how the West has represented Arab sexuality as being the opposite of whatever the prevailing Western sexual norms are. During the Victorian era, when Western bourgeois society was sexually repressed, Western society depicted the Arab world as sexually licentious, with harems full of lusty sheikhs, dancing girls and concubines (think of Flaubert’s travel diary, published in 1996 as Flaubert in Egypt). Then, with the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, Western representations of the Arab world reversed themselves, rendering a geography of sexual repression as a foil to Western sexual freedom.

But what unites this shifting history of representations of Middle Eastern sexuality is a portrayal of dominating, oppressive, and occasionally violent Arab men. This is a dominant representation of Arab sexuality today, and the representation of male Muslims oppressing Muslim women has been used to justify Western military intervention, in an extension of the colonial logic of “white men saving brown women from brown men” (to paraphrase Gayatri Spivak). For example, images of oppressed Afghani women were mobilised on the eve of the invasion of Afghanistan to justify the American invasion as an intervention to save poor Afghani women from their burkas. So I think it’s important to look not only at the history of sexuality in Egypt and elsewhere, but also the history of representations of that sexuality, and how they get deployed politically.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Wynn: It’s a good book for introducing undergraduates to anthropology, because it’s full of gripping stories and introductions to classic theory, but also because I write frankly about what it’s like doing anthropological research, all the ups and downs, everything from homesickness to the sexual harassment I dealt with to the really sweet friendships that developed. I’d assign it with a book by Ghada Abdel Aal called I Want to Get Married! One Wannabe Bride’s Misadventures with Handsome Houdinis, Technicolor Grooms, Morality Police, and Other Mr. Not Quite Rights. It started out as a series of blog posts in Arabic that went viral, and then they were translated by Nora Eltahawy and published by University of Texas Press. It’s hilarious, and it’s a brilliant glimpse of everyday life. The other book I’d pair it with is Nefissa Naguib’s Nurturing Masculinities. It’s about how Egyptian men show they are men by caring for their families. It’s a lovely perspective on masculinity that unsettles Western accounts of Arab masculinity as thuggish and violent.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Wynn: I’m starting a new project that looks at how Egyptians use a continuum of drugs, food, and supplements to manage their health in times of economic precariousness. It sounds like it’s a radically different project, but it actually emerged out of research I was doing on the use of Viagra® (sildenafil) in Egypt. When I was interviewing Egyptians about Viagra, they kept bringing up tramadol, as if the two drugs were interchangeable. Several men (and even one woman!) mentioned taking one Viagra and one tramadol pill every day, like vitamins. The first time someone said that, I thought they just didn’t understand my question. It made no sense. An opioid pain reliever is not the same as an erectile disfunction drug. They have totally different effects on the body. One produces erections, and one… well, it either wilts them or it does nothing, but neuropharmacology would not predict that taking an opioid would make you a better performer in bed! But then people kept equating the two drugs, and I couldn’t explain it away as a misunderstanding, so I started to ask myself: why is that? Eventually, I came to realise that it is precisely because it is a pain reliever that tramadol is used as a substitute for Viagra. In a socioeconomic context where masculinity is demonstrated through providing economically for one’s family (as Nefissa Naguib argues), yet where Egyptian men are fundamentally vulnerable to inflation and job instability, a drug that relieves mental stress and the physical pain of labour is a drug that symbolically restores masculinity. And that got me interested in how drugs and food represent worlds of symbolic meaning.

Lisa L. Wynn is an Associate Professor and Head of the Anthropology Department at Macquarie University in Sydney. She is a medical anthropologist who writes about reproductive health technologies, gender ideologies, affect, and sexuality. She is the author of the book Pyramids and Nightclubs (University of Texas Press, 2007) and, most recently, the co-editor of Abortion Pills, Test Tube Babies, and Sex Toys: Exploring Reproductive and Sexual Technologies in the Middle East and North Africa (Vanderbilt University Press, 2017). Lisa received her PhD in cultural anthropology from Princeton University in 2003. In Australia, her research has been supported by grants and fellowships from the Australian Research Council, and her teaching has been recognised with a national teaching award.

Lisa L. Wynn is an Associate Professor and Head of the Anthropology Department at Macquarie University in Sydney. She is a medical anthropologist who writes about reproductive health technologies, gender ideologies, affect, and sexuality. She is the author of the book Pyramids and Nightclubs (University of Texas Press, 2007) and, most recently, the co-editor of Abortion Pills, Test Tube Babies, and Sex Toys: Exploring Reproductive and Sexual Technologies in the Middle East and North Africa (Vanderbilt University Press, 2017). Lisa received her PhD in cultural anthropology from Princeton University in 2003. In Australia, her research has been supported by grants and fellowships from the Australian Research Council, and her teaching has been recognised with a national teaching award.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com