Tim Wingard

Earlier last month, staff at Berlin Zoo announced that two male emperor penguins, Skipper and Ping, had been given an egg to raise together. A spokesperson for the zoo told the press that they “are acting like exemplary parents, taking turns to warm the egg. They kept trying to hatch fish and stones”.

Skipper and Ping are only the latest in a series of celebrity same-sex penguin couples. In 2004, Dinitia Smith profiled Roy and Silo, a pair of male chinstrap penguins at New York’s Central Park Zoo, in an influential article for the New York Times. Roy and Silo had been given an egg to incubate by their keepers. The pair successfully hatched and raised a female chick named Tango.

Roy, Silo and Tango were swiftly drawn into the fight for LGBTQ liberation. 2005 saw the release of And Tango Makes Three, a heart-warming children’s book which told the story of the penguin family and promoted a message of acceptance for diverse kinds of families. In response, homophobic religious activists campaigned to keep the book out of schools and libraries. Fifteen years later, And Tango Makes Three still courts controversy, featuring regularly on the American Library Association’s annual Top 10 Challenged Books list .

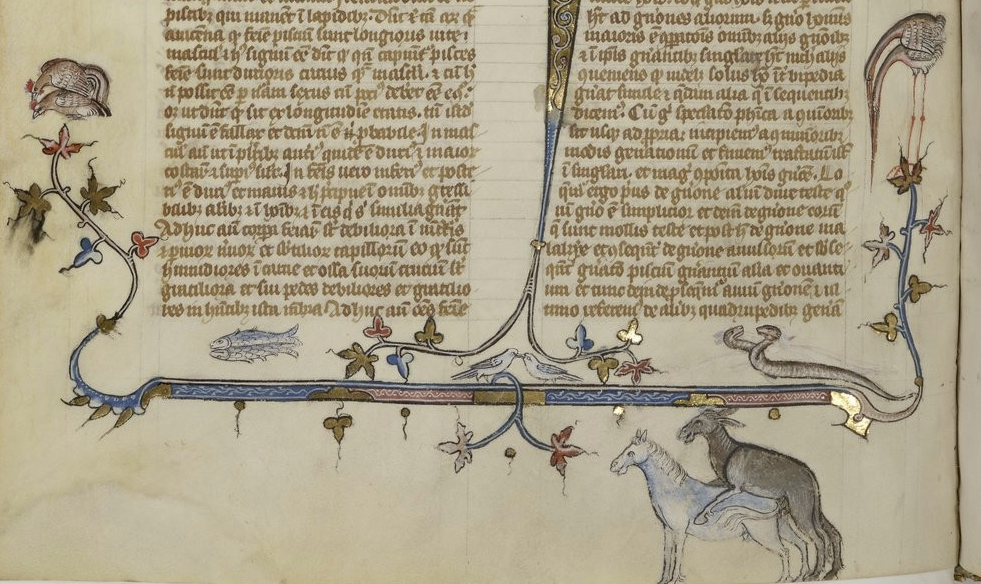

However, the use of animals in debates about human sexual morality is not a new phenomenon, but has been a fundamental part of the history of sexuality. At the end of the fourteenth century, the Dominican prior Roger Dymmok cited the most up-to-date scientific knowledge of his time concerning animal sex in order to intervene in a heated religious dispute.

A new reform movement known to its opponents as ‘Lollardy’ had grown out of the teachings of the Oxford theologian John Wycliffe in the last decades of the 1300s in England. Lollards, or ‘Wycliffites’, did not always agree with each other on many issues. However, like later Protestant reformers they generally shared the conviction that the Church had gained too much secular power and advocated for changes to religious practice. A summary of their arguments, known as the Twelve Conclusions, was presented to Parliament and nailed to the doors of Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral in 1395.

One of their proposed reforms was the abolition of the vows of celibacy by which many groups of men and women – such as monks, nuns, priests and friars – were bound. Individuals who took these vows were forbidden from all sexual activity, including marriage. Lollards argued that there was no justification in the Bible for this requirement and that by restricting peoples’ access to sex through legitimate means, the Church was inadvertently encouraging them to seek release through illicit affairs.

Worst of all, it could lead them to the temptation of sodomy. As Dr Eleanor Janega explains, the medieval category of ‘sodomy’ was fluid and could include acts such as oral sex involving a man and a woman, as well as sex between two men or two women. However, it was the latter which was a particular source of anxiety for the Lollards. As Wycliffe wrote in his Trialogus (early 1380s):

The devil knows to teach youths this most grievous sin apart from the company of women, and especially when a number of virile young men are separated from women, living delightfully and at leisure from work.

To Roger Dymmok, this argument was unacceptable. In his Liber contra XII errores et hereses Lollardorum (1395), penned as a response to the Twelve Conclusions, he wrote that:

It is a great insult to the entire human race to attribute such a need of coitus to them, for man would therefore be of a worse nature than wild animals, who, even if they were to always lack the females of their species, still would never carry out an unnatural act with a male – an act which those advocates of immoderate desires nevertheless assert that human beings are compelled to if they lack the enjoyment of women, that without a doubt is contemptible and detestable to hear, and excessively shameful to the entire human race.

Here, Dymmok was grounding his arguments in the learned scholarship which had been characteristic of the Dominican order since its founding in the early thirteenth century. The philosopher Thomas Aquinas had made a key distinction between humans and animals. Animals, lacking the capacity to reason, could only follow their natural sexual instincts – which drove them to have male-female sex in order to reproduce. Sodomy, which ran contrary to nature, was an exclusively human behaviour, as only humans were capable of acting against natural law. The Lollards’ claim that humans possessed innate sodomitic impulses which could only be managed through legitimate heterosexual outlets was scientifically invalid. Therefore, their argument for the abolition of clerical celibacy was not tenable.

Dymmok’s argument resembles that of modern-day activists, who use new scientific knowledge about animal sex to advocate for LGBTQ liberation. Like them, Dymmok invoked the rhetoric of ‘natural’ sexuality to justify an ethical stance – though for him, this was done to reinforce the status quo, rather than to challenge culturally dominant and oppressive beliefs about sexuality.

Until relatively recently, the basis of Dymmok’s argument – that humans are alone in the animal kingdom in engaging in same-sex intercourse – was accepted orthodoxy in mainstream Western science. It has only been in the last few decades that this narrative has been challenged by researchers, although people who work with animals for a living had often recognised the reality of animals’ sexual diversity long before scientists.

Growing awareness of the prevalence of same-sex intercourse in the animal kingdom has been used to support of stance that homosexuality is a normal part of the human sexual experience. Animal sex was, and remains, political: in June of this year, staff at London Zoo erected banners reading “some penguins are gay, get over it” in the penguins’ enclosure, which is home to no less than three same-sex pairs. In writing our histories of sexuality, then, it is vital that we closely and critically examine the role that animals have played in our conversations about sex.

Tim Wingard is a PhD candidate in Medieval Studies at the University of York, writing a thesis on representations of animals and sexuality in the late middle ages. Tim chairs the Critical Theory for Medievalists Reading Group at the Centre for Medieval Studies and tweets from @TSWingard

Tim Wingard is a PhD candidate in Medieval Studies at the University of York, writing a thesis on representations of animals and sexuality in the late middle ages. Tim chairs the Critical Theory for Medievalists Reading Group at the Centre for Medieval Studies and tweets from @TSWingard

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com