Sarah Levin-Richardson

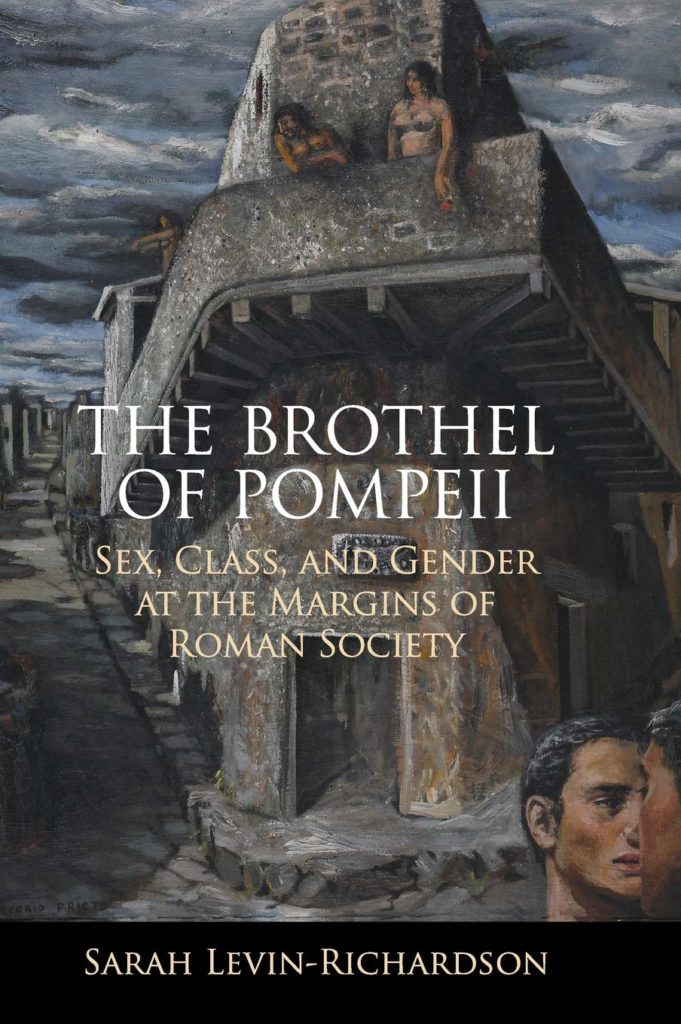

Pompeii’s brothel is the only verifiable brothel from Greco-Roman antiquity. The Brothel of Pompeii: Sex, Class and Gender at the Margins of Roman Society (Cambridge University Press, 2019) tells its story. Taking readers on a tour of all of the purpose-built structure’s evidence, including the rarely seen upper floor, it illuminates the subculture housed within its walls. Here, prostitutes could flout the norms of society and proclaim themselves sexual subjects and agents, while servile clients were allowed to act as ‘real men’. Prostitutes and clients also exchanged gifts, greetings, jokes, taunts, and praise.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

Levin-Richardson: The book captures what it was like in the only assured brothel from Greco-Roman antiquity. I try to answer questions like what the prostitutes and clients chatted about, what the prostitutes did when clients weren’t there, as well as flesh out (as it were) what it was like to buy or sell sex there. Readers follow along as male and female prostitutes attempted to stay connected to their humanity, hopes, and sense of humor, and as lower-status male clients performed sexual acts like “real men” and left their boasts scratched into the walls.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions do you still have?

Levin-Richardson: I first visited Pompeii’s brothel when I was twenty years old, and I was fascinated by the Romans’ generally open attitude towards sex and prostitution. As I read more about Pompeii’s brothel, I realized that scholars were much more interested in what the Romans thought about prostitution writ large than in the real people who had to provide sex or who purchased sex. I wanted to focus on those individuals, and had a sense that doing so would actually change what we think we know about prostitution (and I think the book does show that, but no spoilers!).

I’m humbled every time I talk about the brothel because I always get excellent questions that I’ve never thought to ask. I recently had an undergraduate ask if an “unconquered Victoria” mentioned in the brothel’s graffiti could be the madam, since she’s presumably not having sex with clients herself (and therefore “unconquered” in this context). I had never thought about that possibility before, and some of the big unanswered questions about the brothel are who managed it, who owned it, and what their experiences, hopes, and dreams were.

NOTCHES: This book is clearly about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Levin-Richardson: Slavery is another key theme that runs throughout the book, as many of the prostitutes and clients were enslaved individuals. I hope that the book gives a better sense of how enslaved folks negotiated their power and status not only vis-à-vis their enslavers, but also in their interactions with other enslaved folks. For example, male clients who were enslaved relied on the sexual labor of enslaved prostitutes to temporarily feel like free men, but there were also ways for the prostitutes to take them down a notch, too! I also discuss the economics of prostitution, and ultimately suggest that the purpose-built brothel was a failed business venture—economic historians, take note!

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use, were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

Levin-Richardson: I collected and analyzed as much of the physical evidence about the brothel as possible. I tracked down the various hand-written documents about the brothel’s 1862 excavation in Italian archives, including the list of objects found in the structure. I traced most of these objects through the documentation until their arrival in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, after which the documentation stops—since they weren’t impressive objects, they weren’t given a unique inventory number. It was frustrating to get so close to the objects—to be in the storage rooms of the museum and know that somewhere was the brothel’s lamp—and to be at a dead end.

I also researched the upper floor of the structure, leading to the most profound and moving moment of the whole project for me. In Pompeii’s on-site laboratory, I was able to examine the contents of a small white box—similar to the kind used for a piece of jewelry—and a glass jar with a screw-top lid. Inside the former were a handful of dark objects that looked like cocoa nibs, and the latter held several dark, crumbly, flowering shapes. It was the meal that was about to be cooked when Vesuvius erupted, identified by archaeobotanists as field beans and onions. It brought home the humanity of whoever’s last meal this was, and it was the closest I felt to the people whose lives I was hoping the recapture.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

Levin-Richardson: Yes, in the sense that I wasn’t sure there’d be enough information for chapters on the ground floor’s architecture, on the upper floor, or on male prostitutes. Those turned out to be some of the most interesting chapters, especially the one on male prostitutes! But I always knew that I wanted to have a first half with a rigorous presentation of the physical evidence, combined with a second half that pushed that evidence as far as possible to think through experiences, emotions, subjectivity, and agency.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

Levin-Richardson: I came out in high school at a time when homoerotic sex between consenting adults was a felony offense. If homosexuality came up in the context of a high-school health course, the instructor was legally obligated to tell students that homosexuality was a felony, and leave it at that. I was struck by how something as private and personal as whom I wanted to date was the subject of laws, of education policy, of religious fervor. Since then, I’ve been fascinated by how various societies define and politicize sexual acts and identities.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom, and what would you like students to take from it?

Levin-Richardson: Each chapter is designed to stand on its own, and I wrote with a general audience in mind. The chapters on male clients, female prostitutes, and male prostitutes can be assigned piecemeal in undergraduate or graduate classes on women, gender, or sexuality, while the chapters on the graffiti and frescoes could be useful in courses on social history, epigraphy or Roman art.

One thing I do in my own classes is to create a handout with an assortment of graffiti from the brothel, and have students analyze issues such as the voice or persona of the writer, the content, and relationships to other graffiti nearby. The appendix at the back of my book provides all the brothel’s graffiti in Latin and in translation, and so I encourage instructors to use this to craft their own worksheets. I would love students to know that there’s a whole world of ancient graffiti out there waiting for their fresh eyes and new questions (and that learning/knowing Latin can open up entirely new vistas for thinking about the past)!

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Levin-Richardson: We live in societies that still profit off the lives and labor of those pushed to the margins. Seeing how something similar happened in the microcosm of Pompeii’s brothel will hopefully make us more attuned to ways that we marginalize, exploit, disenfranchise, and demean individuals today. At the same time, these individuals who lived in the most precarious of situations fought back against their exploitation and objectification in every way available to them—they never lost their humanity.

NOTCHES: What are you working on now that this book is published?

Levin-Richardson: I remain interested in the intersection of sex and exploitation, so I’m working on a few small projects on the sexual exploitation and agency of domestic slaves—especially those who were the biological children of their enslavers. My work in that area has taken inspiration from Prof. Saidiya Hartman and her method of critical fabulation, which builds on our available sources (in her case, archives of the trans-Atlantic slave trade) to tell the stories of those at the margins of society from their perspective. The resulting first-person vignettes are both vivid and heartbreaking, and unlike any academic research or writing I’ve done before.

Sarah Levin-Richardson is an assistant professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Washington. Her work examines the intersection of Roman material culture and social history. She has published on topics including the social impact of Pompeian graffiti, the unofficial rules governing Roman sexuality, and the modern reception of Pompeii.

Sarah Levin-Richardson is an assistant professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Washington. Her work examines the intersection of Roman material culture and social history. She has published on topics including the social impact of Pompeian graffiti, the unofficial rules governing Roman sexuality, and the modern reception of Pompeii.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com