Interview by Alicia Decker

Ashley Currier’s Politicizing Sex in Contemporary Africa: Homophobia in Malawi (Cambridge, 2019) charts the emergence and effects of what she calls “politicized homophobia” in Malawi in the twenty-first century. She defines this as “a constellation of anti-homosexuality discourses and practices that political elites deploy to fortify their positions in government, society, and/or religion.” In this provocative book, she illustrates how elites used politicized homophobia to consolidate their moral and political authority. Currier also traces the impact of this virulent discourse on different social movements, including those working on HIV/AIDS, human rights, LGBT rights, and women’s rights. Perhaps most significantly, she intervenes in Afro-pessimist portrayals of Africa as a hotbed of homophobia and unravels the tensions and contradictions underlying Western perceptions of Malawi.

Decker: What motivated you to write this particular book on politicized homophobia in Malawi? Did certain historical developments focus your attention on Malawi?

Currier: I’ve been collecting evidence about politicized homophobia across the African continent since the mid-2000s […] When Ugandan lawmakers introduced the first incarnation of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill in 2009, a particular narrative about “African homophobia” became prominent. As I discuss in Politicizing Sex in Contemporary Africa, non-African pundits, diplomats, and activists intervened in sovereign African nations’ affairs in problematic ways. It became particularly urgent for me, as a white Western academic, to challenge damaging academic claims that the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Bill constituted a form of anti-homosexual “genocide.”

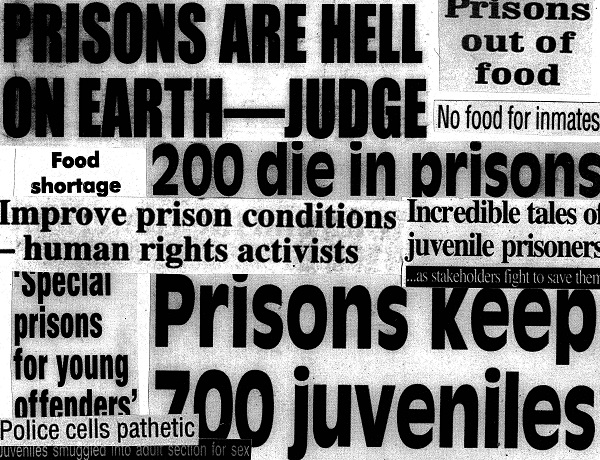

Malawi emerged as an important case for studying politicized homophobia because it had not metamorphosed into a violent vigilantism that the “African homophobia” trope supported. To understand the contours and content of politicized homophobia, I started by looking for anti-homosexuality claims in Malawian newspapers published between 1995—the year in which Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe started denouncing same-sex sexualities publicly and one year after Malawi transitioned into multiparty democracy with President Bakili Muluzi at the helm—and 2016. I thought that if I could trace the “origins” of politicized homophobia, my research could help dismantle dangerous narratives about “African homophobia” that circulate transnationally.

In addition, very few NGOs were publicly lending support for LGBT rights in Malawi. I wanted to understand how and why politicized homophobia affected the strategies and trajectories of different social movements. Because of my previous research on visibility and invisibility strategies in Namibian and South African LGBT organizing, I anticipated the possibility that activists from different movements might be offering behind-the-scenes support and solidarity. While some activists certainly engaged in quieter forms of solidarity so as not to jeopardize their standing within civil society, other obstacles complicated or blocked LGBT rights solidarity.

There is more work to do on researching “homophobia” or cultural and political antipathy toward gender and sexual diversity in southern Africa. Much of this work is historical. As I have written elsewhere, I think that the forms and content of politicized “homophobia” during African national liberation struggles and under European colonialism differ in some ways from contemporary postcolonial and post-independence forms of politicized homophobia. If I can ever find the time, I would love to pore through African national liberation movement archives to trace the possible historical antecedents and expressions of contemporary politicized homophobia.

Decker: Can you briefly walk us through the main argument(s) of your book? What should the reader walk away knowing?

Currier: I make two main arguments in the book. First, politicized homophobia is a strategy that political elites wield to consolidate their power over the state and society. This strategy can involve elites using smear tactics to discredit LGBT people and activists, to threaten to increase penalties for gender nonconformity and same-sex sex, to diminish the status of political opponents, and to besmirch the reputations of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) perceived to be championing LGBT rights. Although politicized homophobia may initially target gender and sexual minorities and their activist defenders, over time elites can deploy it against political opponents who ostensibly have little interest in LGBT rights.

One common tactic is for elites to portray same-sex sexualities as unwanted, Western colonial byproducts and those who defend gender and sexual minorities as being little more than Western puppets. Second, politicized homophobia not only adversely impacts the lives of gender and sexual minorities but also entraps different social movements—namely HIV/AIDS, human rights, LGBT rights, and women’s rights movements. Activists involved with movements perceived to be antagonistic to the state—even movements that had little to do with LGBT rights—could face state repression such as police harassment, arrest, detention, and state-authorized violence. Sometimes, activist organizations confronted criticism from ordinary Malawians who viewed them as betraying Malawian cultural values because they received funding from donors based in the Global North or advocated for unpopular social changes such as LGBT rights. Potential negative consequences deterred some NGO leaders from publicly showing solidarity for LGBT rights. Tracing how the effects of politicized homophobia radiate outward and ensnare unsuspecting social movement actors is essential to understanding the specificity of this phenomenon in postcolonial and post-independence African contexts.

Decker: What is the broader, transdisciplinary appeal of your book? In particular, what does a book about African sexual politics by a sociologist offer historians of sexualities in general and historians of African sexualities in particular?

Currier: Politicizing Sex in Contemporary Africa exposes politicized homophobia as a strategy of statecraft and social re-imagination that shores up heteronormative nationalism and elites’ control of different institutions. By tracing anti-homosexual logics in Malawi’s post-independence period, I am able to document the emergence of the politicization of homosexuality and its metamorphosis in politicized homophobia, which will broadly appeal to historians of sexualities. My use of newspaper data, in particular, will help historically minded readers think through how certain sexual logics come to saturate popular and political discourses in different times and places and how contradictory logics can coexist in the same homophobic threat or practices. Historians of African sexualities will be interested in thinking through the continuities and discontinuities of (anti-homo)sexual logics that have emerged in Malawi and whether and how such logics did or did not manifest in other African historical and social contexts. I can clearly see the ethical quandaries in looking for evidence of “homophobia” in African pasts. However, there may be inventive ways for historians to cull out historical antecedents of present-day homophobias, queerphobias, and transphobias without assuming the existence of a static “history of an African homophobia.”

Decker: Politicized homophobia is a historical construct. Can you briefly discuss how it evolved in Malawi? What would it take to eliminate this toxic discourse?

Currier: I’m so glad you seized on this point I make in the book. Homosexuality did not materialize as a polarizing political topic in Malawi until the mid-2000s. I attribute the politicization of homosexuality to two episodes in Chapter One: 1) a human rights NGO using the constitutional review process to recommend that lawmakers rescind the anti-sodomy law and amend the nondiscrimination clause to include sexual orientation, which generated an outpouring of antigay vitriol from political, religious, and traditional leaders; and 2) local resistance to homosexuality in an Anglican parish, after rumors that the white British man selected as bishop was gay and supported LGBT rights. Politicization gave way to politicized homophobia with the prosecution of Tiwonge Chimbalanga, a transgender woman, and Steven Monjeza, a cisgender man, for violating the anti-sodomy law. Not only did this case concentrate national and international attention on LGBT rights organizing in the country, but it also constituted a turning point in civil society as President Bingu wa Mutharika’s government escalated state repression of social movements perceived to challenge the government’s authority. An argument I make in the book’s conclusion is that because politicized homophobia has a history, it can have an end. Although outsiders can provide material and nonmaterial support for Malawian anti-homophobic initiatives, Malawians should helm these campaigns.

Decker: In Chapter 3 you discuss politicized homophobia as a “scavenger ideology.” What do you mean by that?

Currier: Following George L. Mosse, I treat politicized homophobia as a changeable ideology and strategy that grafts on to other discriminatory ideologies such as racism, xenophobia, and misogyny. Because elites often deploy politicized homophobia as a form of defensive posturing, intending to deflect public scrutiny away from abuses of power, they may unleash it alongside other discriminatory claims. In the same speech a state leader may encourage police to arrest gender and sexual minorities and rail against foreigners resulting in a combination of xenophobia and homophobia. The “scavenging” feature of politicized homophobia demonstrates how portable it is to other contexts and how easily elites in different times and places can populate this strategy with images, threats, and actions that will resonate with local audiences. However, I do not conflate politicized homophobia’s “scavenger” qualities with sex panics, as I explain in the introduction. To put it simply, I worry that labeling politicized homophobia a “sex panic” will feed into and aggravate problematic narratives about the African continent being full of people who are easily brainwashed into participating in “sex panics,” narratives that are simply untrue.

Decker: In Chapter 5, you document the various harms faced by LGB Malawians as a result of politicized homophobia. Later, in the conclusion, you discuss the problems of documenting “African homophobia” and how such efforts often feed into racist, ahistorical understandings of Africa. How do you document the “violence” without reinforcing problematic stereotypes?

Currier: In this chapter, I emphasize LGB Malawians’ perceptions that politicized homophobia had disadvantaged them in particular ways while maintaining that I was not alleging that politicized homophobia had uniformly caused all Malawian sexual minorities harm. It’s a fine distinction but an important one because we need to be cognizant of what this framework enables in terms of research possibilities and what it simply cannot (and should not) do. First, it’s a bad idea to impute one-to-one causality in the case of politicized homophobia. By this, I mean that we shouldn’t assume that because a politician makes antigay threats in the nation’s capital, neighbors will violently attack a masculine-presenting lesbian woman in their community on the same day. I do not dispute the perceptions of survivors of such violence that heightened antigay vitriol emboldened perpetrators of verbal, physical, or sexual violence. However, it is quite possible that this attack is an outcome of a cascading chain of events that may only partly involve neighbors’ anti-lesbian antagonism, as Doug Meyer suggests. Although survivors cannot always see these mechanisms at work, it does not invalidate their perceptions that homophobia was the primary force motivating the hostility they experienced. Intersecting inequalities, such as gender identity and presentation, class, ethnicity, and age, may influence and structure what observers first diagnose as homophobic antipathy.

Second, we should recognize the malleability of politicized homophobia, which does not inflict the same harm on all people. Documenting the range of harms caused by homophobia prevents observers from making inaccurate generalizations that all homophobic antipathy yields the same outcomes. Anti-lesbian hostility, in some cases, entails threats of specific sexual violence against queer women; not all sexual minorities are subjected to these threats. Third, catastrophizing about “African homophobia” reproduces racist, ahistorical mischaracterizations about “African sexualities.” On one hand, I wanted to document LGB Malawians’ perceptions about how politicized, social, and religious homophobias had touched their lives. Activists, policymakers, and elites need to hear from queer Africans about their experiences with homophobia. On the other hand, I am concerned about associating queer Africans only with their experiences of victimization because people can willfully manipulate my research findings and framework to flesh out their preferred narratives of “rescuing” this vulnerable group. One reason I opted to do this research in Malawi was because the country had not been publicly associated with violent antigay vigilantism, which is a singularly dangerous way to characterize the plastic phenomena of homophobias, queerphobias, and transphobias.

Decker: I am often asked to serve as an expert witness for LGBT Ugandans seeking asylum in the USA. Given the “homoprotectionist” impulse, particularly on behalf of those in the Global North to “save” queer Africans in the Global South, should academics “help” in asylum cases? What are the politics of this dynamic?

Decker: You’re asking a tough question that pits individuals’ agency against larger structures that produce “homoprotectionism.” I try to help individual asylum seekers and analyze sociopolitical developments that generate the false binaries of the “good Global North” and the “bad Global South.” I offer expert testimony to assist gender and sexual minorities from African countries in which I have done research, while maintaining the ability to critique national(ist) and supranational practices, policies, and priorities that yield homoprotectionist narratives and principles. Let me be clear: I do not offer expert testimony or consult about cases involving African countries in which I have not conducted research. Although I realize that some legal experts might argue that accepting a fee in exchange for serving as an expert witness legitimizes this practice and generates some objective distance for the academic, I have never personally accepted fees for my expert testimony, as I regard this as an important public service.

Decker: Where do you go from here? Do you have ideas for your next book project?

Currier: I recently realized that I’m working on a trilogy related to African gender and sexual diversity organizing. The third and final installment in this series emerges directly from my research in Malawi. In my first complete draft of the book manuscript, I included a chapter on the “limits” of politicized homophobia: circulating antigay discourses that did not become subsumed within politicized homophobia. I focused particularly on journalistic reporting about instances of sexual violence perpetrated by adult men against boys or men. I became interested in understanding what has contributed to the invisibility of “sex” in carceral context, including pleasurable sex and sexual violence. Although the larger project broaches the politics of prison sex in southern Africa, I am looking first at how and why different Namibian social movements—children’s rights, human rights, LGBT rights, prison-reform, and women’s rights movements—seem not to have mobilized around prison sexual violence. From a distance, there appears to be little organizing around this issue that could draw multiple movements into a coalition. However, different social movement groups may be working surreptitiously on this admittedly unpopular issue.

Ashley Currier is a professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Cincinnati. She researches gender and sexual diversity politics in southern and West Africa. Her books include Out in Africa: LGBT Organizing in Namibia and South Africa (U of Minnesota P, 2012) and Politicizing Sex in Contemporary Africa: Homophobia in Malawi (Cambridge UP, 2019). Her research has appeared in Australian Feminist Studies, Critical African Studies, Feminist Formations, Gender & Society, GLQ, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Mobilization, Politique Africaine, Qualitative Sociology, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Social Movement Studies, Space and Polity, Studies in Law, Politics, and Society, and Women’s Studies Quarterly.

Ashley Currier is a professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Cincinnati. She researches gender and sexual diversity politics in southern and West Africa. Her books include Out in Africa: LGBT Organizing in Namibia and South Africa (U of Minnesota P, 2012) and Politicizing Sex in Contemporary Africa: Homophobia in Malawi (Cambridge UP, 2019). Her research has appeared in Australian Feminist Studies, Critical African Studies, Feminist Formations, Gender & Society, GLQ, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Mobilization, Politique Africaine, Qualitative Sociology, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Social Movement Studies, Space and Polity, Studies in Law, Politics, and Society, and Women’s Studies Quarterly.

Alicia Decker is an associate professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and Africa studies at the Pennsylvania State University, where she also co-directs the African Feminist Initiative with Gabeba Baderoon and Maha Marouan. Decker is the author of In Idi Amin’s Shadow: Women, Gender, and Militarism in Uganda (2014), and co-author with Andrea Arrington of Africanizing Democracies: 1980-Present (2015). She is co-editor of the Oxford Encyclopedia of African Women’s History (forthcoming 2020) and the series co-editor of War and Militarism in African History (Ohio UP). Her scholarly articles have appeared in the International Journal of African Historical Studies, Women’s History Review, Journal of Eastern African Studies, History Teacher, Afriche e Orienti, Feminist Studies, Journal of African Military History, and Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, as well as various edited book collections.

Alicia Decker is an associate professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and Africa studies at the Pennsylvania State University, where she also co-directs the African Feminist Initiative with Gabeba Baderoon and Maha Marouan. Decker is the author of In Idi Amin’s Shadow: Women, Gender, and Militarism in Uganda (2014), and co-author with Andrea Arrington of Africanizing Democracies: 1980-Present (2015). She is co-editor of the Oxford Encyclopedia of African Women’s History (forthcoming 2020) and the series co-editor of War and Militarism in African History (Ohio UP). Her scholarly articles have appeared in the International Journal of African Historical Studies, Women’s History Review, Journal of Eastern African Studies, History Teacher, Afriche e Orienti, Feminist Studies, Journal of African Military History, and Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, as well as various edited book collections.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com