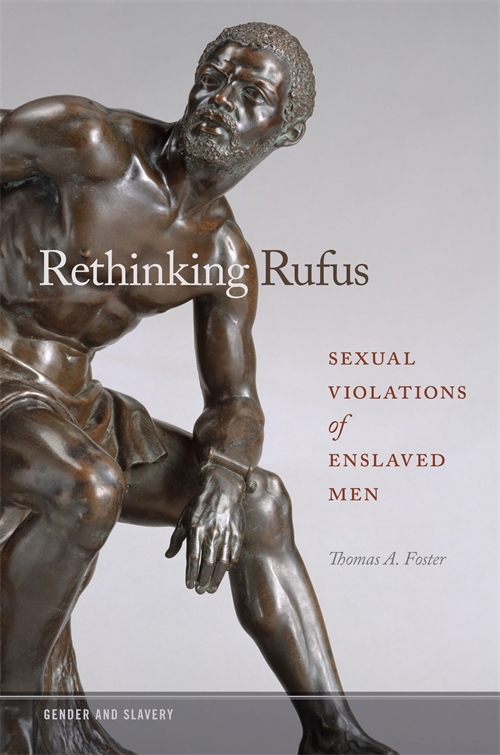

Rethinking Rufus is the first book-length study of sexual violence against enslaved men. In this extract, Thomas Foster introduces us to Rufus and Rose, the enslaved woman with whom he was coerced into sexual union. Their story is not unknown to historians, but by examining Rufus’s experience, Foster illuminates how the conditions of slavery gave rise to a variety of forms of sexual assault and exploitation that affected all members of the community. NOTCHES is grateful to the University of Georgia Press for permission to reproduce this extract.

Rufus landed hard on the dirt floor. Rose’s kick had caught him off guard when she fought him. He had wanted to lie down. He was exhausted. The Texas sun had drained his energies. He now knew that Rose and he wouldn’t sleep together that night, but he knew they would eventually have to. It was how things worked under slavery. Some called him a bully, but he knew who held the real power. Days before, his master, Hall Hawkins, told him that it was time for him to make babies. Hawkins told him to pair up with Rose. He didn’t know her well but had seen her around, working. Not who he would have picked. He liked another young woman, but in this life you did as you were told or you paid the consequences. Rufus was no stranger to being told what to do with his body. Lift this. Carry that. Sleep here. Move now. Sleep with her and make babies. He hated Hawkins for telling him whom to have sex with, but he knew he had no choice. He’d been poked, prodded, stripped, whipped, leered at, and now mated. At times he wondered if they even knew he was a man. Life with Rose would work out. It was better than getting lashed for resisting, and he had wanted to have children someday and head a household. But for now, he found himself on a dirt floor, tasting blood and faced with a woman wielding a fireplace poker. Tonight, he would sleep outside.

***

Rufus was enslaved in Texas in the nineteenth century, but we know few other biographical details about him. We do not know his last name or where he lived after slavery ended. What we know about Rufus’s own experiences during slavery comes to us from an interview with Rose Williams that took place in the early twentieth century with a representative of the federal Works Progress Administration. She characterized Rufus as a “bully” and described resisting him as he attempted to crawl into her bed. Rose’s interview has been often reprinted and is well known as a vivid account of the sexual coercion of enslaved women. By imagining their clash from Rufus’s perspective, we can begin to see that our current understanding of sexual violence under slavery is limited. A generation ago, Wilma King noted that discussion of Rose’s experiences took place “without raising questions about its impact on her spouse.” This is the first study to respond to that observation with a focus on Rufus and enslaved men.

Rethinking Rufus examines the sexual conditions that slavery produced and that enslaved men lived within, responded to, and shaped. To tell the story of men such as Rufus, this book queries the range of experiences for enslaved men. Although focused on the United States, it employs a broad chronological and geographic scope. It uses a wide range of sources on slavery—early American newspapers, court records, slave owners’ journals, abolitionist literature, the testimony of former slaves collected in autobiographies and in interviews, and Western art—to argue that enslaved black men were sexually violated by both white men and white women. Rethinking Rufus is a history of how the conditions of slavery gave rise to a variety of forms of sexual assault and exploitation that touched the lives of many men, their families, and their communities.

The topic of sexual violations of enslaved men has long been in cultural circulation and is not unfamiliar. [E]nslaved people referenced sexual abuse of enslaved men in their accounts of slavery produced before and after emancipation. Through the twentieth century and right up to the present day, fictionalized accounts of slavery have contained references to men sexually accosted by enslavers, men and women, and forced to reproduce. […]

The study of enslaved men has not covered sexual assault not only because of the legacy of slavery, which characterized black men as hypersexual (and therefore always willing sexual participants) but also because of the historical and enduring understandings of sexual assault. For centuries, our culture has tended to view rape in archetypal ways as the violent sexual assault of a white woman by a stranger, most often a man of color and/or lower status. The early American legal system established sexual assault as a gendered crime, one that by definition covered only free women. In application of the law, its coverage was even narrower, with biases, especially along lines of race and status, influencing outcomes. As Sharon Block has shown, early American print depictions of rape most often highlighted the male guardian as the victim of the male perpetrator. In her study of changing conceptions of rape, historian Estelle Freedman has shown how the “meaning of rape is . . . fluid, rather than transhistorical or static,” how “its definition is continually reshaped,” and how its history is largely about changing understandings of “which women may charge which men” with the crime. In the era of slavery, Anglo-American culture already embraced a message about black men as particularly sexual, prone to sensual indulgence, and desiring white women. In the late nineteenth century, activists argued for a broadened understanding of rape, one that included sexual assault of African American women but still did not consider the inclusion of men as potential victims.

By the time of the mid-twentieth-century women’s movement, feminist theory had shifted the cultural understanding of rape from a crime of passion, usually committed against women who bore responsibility for their victimization, to an expression of violent power, specifically as a tool of the patriarchal oppression of women. This conceptualization has successfully allowed us to better understand sexual assault and rape as a display of power rather than of sexual desire. It does not, however, help us fully understand sexual assault. Even a cursory consideration of sexual assault today can readily point to examples of abuse of power that do not include the shoring up of patriarchy. Sexual assault also happens to boys and men: dependent elderly men who are assaulted by caregivers; incarcerated men by inmates and male and female guards; boys and men in war; prisoners of war or “enemy combatants”; boys and underage youth by male and female teachers, ministers, babysitters, coaches, senior teammates, senior fraternity members—the list is long.

Using the term “rape” to describe sexual violations of men only in the title to this introduction, and even there only hesitatingly posed in question form, signals that the work does not radically revisit or reclaim the word. It may well be too entrenched in historical roots to recover and be useful today for both men and women. But Rethinking Rufus does argue that the peculiarities of slavery meant that enslaved men were victimized and sexually assaulted in complex ways and in a manner that may only best be thought of and called rape, even if our available vocabulary remains insufficient for such a study.

Rethinking Rufus takes as a starting point the basic recognition that enslaved men could not consent to sexual intimacy with enslavers because of their legal status as property and because of their vulnerability as enslaved people within the hierarchical ordering of society.

Thomas A. Foster is an associate dean for faculty affairs and a history professor at Howard University. He is the author or editor of six books, including editor of Documenting Intimate Matters: Primary Sources for a History of Sexuality in America, author of Sex and the Founding Fathers: The American Quest for a Relatable Past and editor of Women in Early America. He tweets at @ThomasAFoster.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com