Hugh Mac Neill

It’s another Friday night in Pittsburgh’s gay district, Liberty Avenue. Justin, the TV show Queer as Folk’s blonde-haired blue-eyed main character, scans the street adorned with pride flags and enticing neon bar signs. He’s cruising, but he’s not looking for a good time. Justin, along with a handful of other young, mostly white queers, is taking his shift as a member of the Pink Posse—a militant patrol group organized against the homophobia that plagues the neighborhood. There is, of course, a uniform: light pink tops, military style gray jackets, and cropped haircuts.

Like the nightclubbers flocking to the dance floor, the Pink Posse is sure to find some action. Half a block ahead of the group, a man leans out of the passenger side of a moving car to harass a gay couple meandering down the street. He’s smiling as he yells at them. This isn’t his first pass down Liberty Avenue, and he’s relishing the rush this premeditated attack will be sure to produce. “Hey faggot, wanna suck my dick?” he calls out. There is no response, and as viewers we know there is none needed. The couple looks down in shame. The man returns to his car.

The Pink Posse springs into action. They rush to the scene, kicking dents into the car’s front door and demanding the man answer for the homophobic insult. He confronts the group, more shocked than angry that his actions produced anything other than shame. He’s right to be shocked; the Pink Posse far outnumber him. And when words spill over into a fight, they quickly overpower the man and strip him naked from the waist down. He returns to his car, no longer smiling, humiliated.

While the show is best known for its softcore porn and melodrama, in this instance, Queer as Folk delivers a different yet equally titillating scene: the fantasy of the rebuked homophobe. The Pink Posse may have reversed the shame associated with queer visibility, but this small victory, in which the victims of homophobic abuse become the perpetrators of sexual harassment, is only temporary. The man in the car is sure to return in some form or another. Homophobia cannot be patrolled out of existence. However, these moments provide enough satisfaction, enough thrill, enough of a semblance of control for the Pink Posse to don their uniforms and take to the streets once more. And this story of a queer vigilante group is not merely the product of the soap opera’s writing room; it’s a page torn out of the history of gay liberation.

In the late 1970s, gay patrol units formed in US cities including San Francisco and New York City. While short-lived—most only lasted a few years—these units joined other queer political action groups created to protest American imperialism, provide community aid, publish small-scale periodicals, and join the efforts of the feminist and Black power movements. As anthropologist Christina Hanhardt writes in her book Safe Space, these patrol units, organized predominantly by white gay men, aspired to prevent unlawful arrests by local police forces and, if possible, to retaliate against homophobia in action. These groups’ indicate increasing militancy following the 1969 Stonewall Riots and the growing sentiment that gay people could foster and defend neighborhoods catering specifically to their community. Like the Pink Posse, patrol groups took on a variety of colorful names such as the Butterfly Brigade and the Society to Make America Safe for Homosexuals (SMASH). To most white Americans, these vigilantes-cum-law enforcement officers garnered little attention. All, that is, except one: San Francisco’s Lavender Panthers.

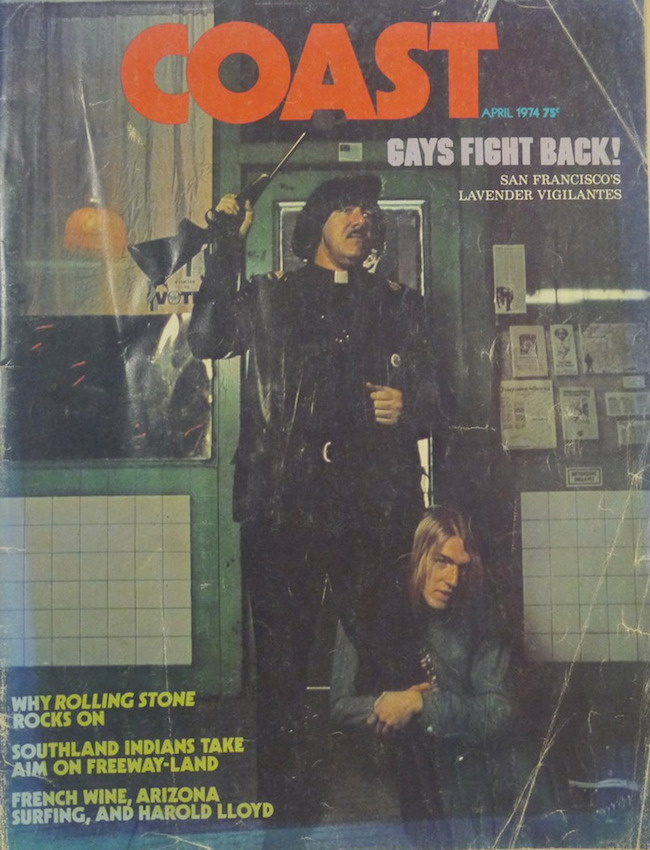

Their name, The Lavender Panthers, was an appropriated rendition of the Black Panther Party, a Black revolutionary organization founded just a stone’s throw away in Oakland. Piquing the interest of both Rolling Stone and Time magazine, their queer proximity to Black radicalism hinted at a coalition in the making. The Lavender Panthers, however, could not be ideologically farther from their Oakland neighbors. In an interview for Coast magazine, the group’s leader Raymond Broshears—a defrocked Southern Evangelical preacher—described a typical neighbourhood sweep for potential homophobes:

Three blacks, wearing pimp garb and driving around in a white Cadillac, are believed responsible for five beatings and robberies in the area over a two-month period. ‘I’d hate to be those black motherfuckers when we find them,’ Broshears says with a tight, little smile. ‘Because you know what they’re gonna be when we get a hold of them?’ The little smile gets a bit wider as he leans over the desk and hisses, ‘N*****s!’

In an attempt to eliminate homophobia, patrol groups like the Lavender Panthers rallied around their whiteness to produce a sense of safety. Broshears’s description of an imaginary lynching, where gay residents transform into murderous vigilantes, spoke less to their original claim of community organizing and more to their connections to power. These tactics were far from isolated, and Hanhardt’s book describes a number of methods used by white queers to separate themselves from their non-white counterparts. In San Francisco, queers of color raised concerns over the Butterfly Brigade’s targeting of Latinos in the neighborhood, despite the fact that most of the homophobia documented came from white male suburbanites. Similarly, in New York City, the Society to Make America Safe for Homosexuals (SMASH) closely monitored neighborhoods of color without any evidence to indicate a greater level of homophobia in those areas.

Although local law enforcement certainly antagonized white queer patrol units through unlawful arrest and harassment, the two groups could also stand together in their commitment towards racialized violence. Through this broader structural relationship, groups like the Lavender Panthers and SMASH became indistinguishable from their antagonists. As critical theorist Frank B. Wilderson III writes, “white people are not simply ‘protected’ by the police, they are—in their very corporeality—the police”. Surveilling the streets donning queer aesthetics may have signified safety for San Francisco’s and New York City’s white gay residents, but for those that fell outside these racialized boundaries, gay patrol units like these functioned as yet another pig in lipstick.

The emergence of the Lavender Panthers, their ideological siblings, and their on-screen adaptations complicate the history of gay community formation following the Stonewall Riots. What has commonly been understood as a narrative of increased inclusion and community visibility actually activated a series of deeper exclusions. Anti-blackness and xenophobia created promises of increased safety and pathways to full-fledged citizenship that would otherwise not be offered to white queers. As such, this love affair between pink-washed patrol units and the white fantasy of safety represents the perennially discounted question: What does queer space aim to protect?

Hugh Mac Neill is an aspiring oral historian and recent graduate of Dartmouth College. They specialize in the critical history of conservatism, queer community formation, capitalism, and religion. You can reach them at hughmacneill@gmail.com.

Hugh Mac Neill is an aspiring oral historian and recent graduate of Dartmouth College. They specialize in the critical history of conservatism, queer community formation, capitalism, and religion. You can reach them at hughmacneill@gmail.com.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com