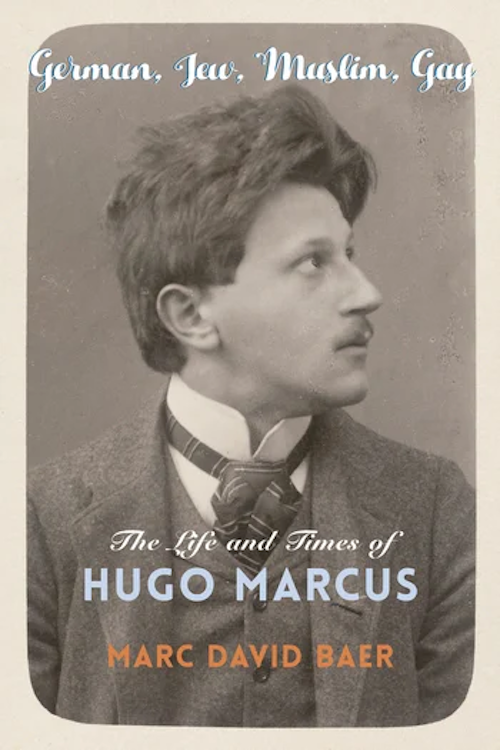

German, Jew, Muslim, Gay is the first biography of Hugo Marcus (1880–1966), whose unique synthesis of multiple identities challenges our understandings of interwar and postwar Europe. Marcus was born a German Jew who converted to Islam and became one of the most prominent Muslims in Germany prior to the Second World War. Before the war, Marcus was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp from which he was released and later escaped to Switzerland. He was also a gay man, and although he never called himself gay, he fought for homosexual rights and wrote queer fiction while in exile.Through an examination of Marcus’s life and work, Marc David Baer illuminates the complexities of twentieth-century Europe’s religious, sexual, and cultural politics.

NOTCHES: Why did you write this book?

Marc David Baer: Ten years ago, I was living in Berlin, working on a very different project. I was researching the descendants of the followers of the seventeenth-century Jewish spiritualist Sabbatai Zevi who, rather than prove his messianic powers by conducting a miracle, converted to Islam before the Ottoman Sultan. Oddly, hundreds of his Jewish followers also converted to Islam. They created a new, secret religion at the intersection of Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah) and Muslim spiritualism (Sufism). Their descendants, the Dönme, exist to this day.

I was following the fate of the Dönme in Weimar and Nazi Berlin when I also learned that the leading German Muslim at that time was a Jewish convert to Islam, named Hugo Marcus (1880-1966). His life and work gave me the opportunity to explore not only religious conversion but also the creative, subversive, counterintuitive work people do with hegemonic attempts to classify them. Such groups as the Dönme or individuals as Hugo Marcus, facing the limits of classifications, boundaries and definitions, happily smash them. In so doing they create something far more profound.

I spent ten years reading thousands of pages of material in Basel, Bern, Zürich, Berlin and LA, including Marcus’s unpublished and published writing: German-language private letters, erotic poetry, mosque lectures; police and concentration camp records; philosophical, pacifist, avant-garde, Islamic writing; as well as homoerotic short stories and novellas. Reading this material, I realised what was so subversive about this man—he was able to be simultaneously German, and Jewish and gay and Muslim. Marcus created his own Islam, whose first pillar, rather than the profession of faith (that ‘there is no God but God and Muhammad is His prophet’), was purity. Purity included love, beauty, pacifism and brotherhood. He created an Islam which included ‘exceptional cases’, for instance gay men, like himself.

Here is a man who was Jewish and Muslim and always claimed, defiantly, not only that he was German, but that the ideal German was a gay Muslim! And this claim, which he expressed in word and deed for decades, was despite the German anti-Semites, homophobes and Islamophobes who persistently denied and even, in the Nazi case, stripped him of his right to call himself a German.

NOTCHES: Why would he say that the ideal German was gay and Muslim? Were there (are there) other Germans who felt (feel) that way?

MDB: In his mosque lectures and publications, including his own conversion narrative, Marcus promoted the utopian project of an Islam for Germany. He did this by demonstrating the similarities between Muslim and German values and philosophy, and by presenting the ‘Muslim’ views held by the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Marcus took what Goethe expressed in some of his poems and other writing as a precedent for his own. In Notes and Commentary to West-East Divan, Goethe writes:

‘The truly sublime Qur’an attracts me, astonishes me, and in the end elicits my admiration.’

In West-East Divan, Goethe writes:

‘I have contemplated devoutly celebrating that holy night, when the Qur’an, in its entirety, was revealed to the Prophet from on high.’

‘The writer of the book [West-East Divan] does not even reject the supposition that he may be a Muslim.’

‘I find it foolish, and quite odd, / That stubborn folk seek to deny: / If “Islam” means we all serve God, / We all in Islam live and die.’

Members of the first generation of German Muslims, including Marcus, took Goethe’s statements at face value. Goethe was not a Muslim; he was not a member of any religion. But Marcus used what he considered Goethe’s ‘conversion’ to make a bold argument about German and Islamic cultures. What Marcus envisioned was an Islam rooted in Goethe’s Weimar classicism in the Enlightenment era. He saw being German as viewing the world in ‘the Muslim’ Goethe’s terms; for Germans, being Muslim was to read Islam in a Goethean way.

Just as he had modeled his own conversion narrative on the ‘conversion’ narrative of Goethe, Marcus turned to the writing and life of Goethe as personal and literary precedent and legitimizer for his own gay feelings and identity. For just as Goethe’s poetry and prose exhibit unmistakable praise for Muhammad and Islam as well as apparent adoption of Islamic views, so does Goethe’s writing offer explicit homoeroticism, giving rise to queer readings of the man and his age. We find this in Goethe’s early poetry, such as ‘To the Moon’, and ‘Ganymede’, as well as in his prose, including Letters from Switzerland. Goethe writes about pederasty, the admiration of male beauty, and love between male friends:

‘In actual fact, Greek pederasty is based on the fact that, measured purely aesthetically, the man is after all far more beautiful, more excellent, more perfect than the woman. . .Pederasty is as old as humanity, and therefore it may be said that it is rooted in nature.’ (Goethe’s Conversations)

‘I like to see young creatures gather around me and befriend me. . . One unpleasant experience after another failed to bring me back from this inborn drive, which at present, in the event of the most explicit conviction, still threatens to lead me astray.’ (Poetry and Truth)

‘What a glorious shape my [nude] friend has! How duly proportioned all his limbs are! what fullness of form! what splendor of youth! What a gain to have enriched my imagination with this perfect model of manhood!’ (Letters from Switzerland)

In West-East Divan, written when Goethe was mature, he writes:

‘But my love is yet more dear / When a mem’ry kiss I win./Words go by and disappear. / Yet your gift remains within.’ (The youth cup bearer in West-East Divan).

While Goethe and those like him could not have had a gay identity, which emerged in the late nineteenth century, they were part of a subculture based on same-sex desire whose signifiers prefigured the identity of the modern homosexual.

NOTCHES: What were those signifiers?

MDB: Among the signifiers were Greek antiquity and culture, particularly the propensity for male–male love such as that of Ganymede, a model for the socially acceptable erotic relationship between a man and a youth. Other signifiers included Biblical traditions and orientalist references to classical civilization and sexuality stretching from the Muslim world to Italy. They could also include Switzerland and Freundesliebe, meaning the cult of friendship.

Friendship between men, which surpassed a man’s love for a woman, was seen as an effusive, passionate, and intimate relationship. If these were signifiers of homosexuality for Goethe, so are they in the fiction of Marcus. In his writing one finds the erotic themes of the beauty of the male nude, the superiority of male–male unrequited desire to male–female consummated love, temptation and awakened yet never consummated desire, the meaning of true friendship, Christian imagery, and ancient Greek mythology.

NOTCHES: Marcus died before Stonewall. What additional significance does your biography of Hugo Marcus offer us today?

MDB: The themes of this book speak to issues that continue to resonate in Europe today and directly impact many people. Queer Muslims are hardly conceivable in mainstream and right-wing discourse about Islam and homosexuality. How much more was this the case for a Muslim man in Europe before gay liberation? Unlike today, however—following the mass migration of Muslims to the continent since the Second World War—no one would ask Marcus, a German, ‘Where do you come from?’. Not entirely unlike the Far Right today, however, the Nazis told him as a Jew, ‘You do not belong here’. His answer, ‘I am from here’, was as unacceptable to the Nazis then as it is to Islamophobes in Europe today. I hope that this first biography in any language of Hugo Marcus helps us to simultaneously queer Jewish and Islamic Studies and perhaps even German Studies.

Marc David Baer is a professor of international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science. In addition to German, Jew, Muslim, Gay, Baer has published four books: Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe; The Dönme: Jewish Converts, Muslim Revolutionaries, and Secular Turks; At Meydanı’nda Ölüm: 17. Yüzyıl İstanbul’unda Toplumsal Cinsiyet, Hoşgörü veİhtida (Death on the Hippodrome: Gender, Tolerance, and Conversion in seventeenth-century Istanbul); Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide.

Marc David Baer is a professor of international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science. In addition to German, Jew, Muslim, Gay, Baer has published four books: Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe; The Dönme: Jewish Converts, Muslim Revolutionaries, and Secular Turks; At Meydanı’nda Ölüm: 17. Yüzyıl İstanbul’unda Toplumsal Cinsiyet, Hoşgörü veİhtida (Death on the Hippodrome: Gender, Tolerance, and Conversion in seventeenth-century Istanbul); Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I appreciate this piece. But I object to calling Marcus gay if he didn’t say he was gay. Homosexuality (same-sex attraction) is one thing; the subculture or social group known as “gay” is another thing.