Ula Klein

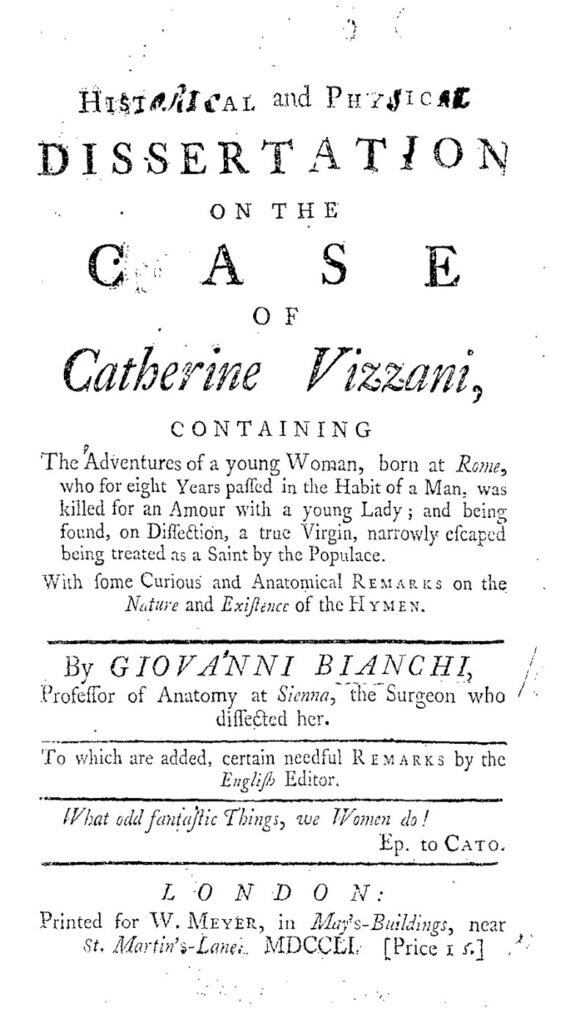

In 1751, a short pamphlet was published in London entitled, An Historical and Physical Dissertation on the Case of Catherine Vizzani. The full title of the publication warrants some reflection:

An Historical and physical dissertation on the case of Catherine Vizzani, containing the adventures of a young woman, born at Rome, who for eight Years passed in the Habit of a Man, was killed for an Amour with a young Lady; and being found, on Dissection, a true Virgin, narrowly escaped being treated as a Saint by the Populace. With some curious and anatomical remarks on the nature and existence of the hymen. By Giovanni Bianchi, Professor of Anatomy at Sienna, the Surgeon who dissected her. To which are added, certain needful remarks by the English editor.

Expert sleuthing by literary scholar Roger Lonsdale has confirmed that the English editor who translated the story of Vizzani and appended some “needful remarks” was none other than John Cleland, the author of his own rather scandalous erotic novel of 1749, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure; or, Fanny Hill. The difference here, though, is that the story of Vizzani was meant to be a biography of a real person rather than pure fiction.

Vizzani’s story is one of several featuring persons assigned female at birth, but who, at some point in their lives, decided to wear men’s clothing and “pass” as men. If and when those persons decided to marry a woman and live with her as husband and wife, they were often called “female husbands” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Cross-dressing was not unknown at this time; and while the term “cross-dressing” has been all but dropped from modern LGBTQ parlance, scholars of history of sexuality still tend to use it for persons like Vizzani because we really have no way of knowing if Vizzani thought of themselves as queer, lesbian, transgender, genderqueer, non-binary or something else entirely–especially since that terminology is so contemporary and, moreover, sexual and gender identity were thought of in patently different ways in the eighteenth century. “Cross-dresser”, then, serves as a kind of baggy term that indicates a behavior rather than an identity; a term capacious enough to suggest any one of these possibilities without ruling out any either.

Vizzani plays an important role in tracing transgender identity in the past; as the subtitle to their story tells us, Vizzani lived as a man named Giovanni for eight years in Italy and is often referred to by the masculine pronoun in the text.

Interestingly, though, the translator of the text, Cleland, seems much more concerned with Vizzani’s desires rather than their gender identity; throughout the biography, it is Vizzani’s desires for women that mark them as dangerous and transgressive: for Cleland, Vizzani’s cross-dressing is merely a means to an end. In this way, Vizzani’s story also plays an important role in lesbian history, especially early on, when Vizzani begins an amorous liaison with a woman before they begin dressing in men’s clothes. Regardless of Vizzani’s own identifications, then, the other woman–her paramour–expresses same-sex desire in the text.

Vizzani’s story takes a turn towards the tragic when they are shot in the leg escaping with a lover and her sister; wounded, Vizzani is taken to a local hospital where a “leathern Contrivance, of a Cylindrical figure, which was fastened below the Abdomen, and had been the chief Instrument of her detestable Imposture” is found: a dildo.

Both Vizzani’s body and her dildo are “dissected” after her death: “the leathern Machine, which was hid under the Pillow, fell into the Hands of the Surgeon’s Mates in the Hospital, who immediately were for ripping it up, concluding that it contained Money, or something else of Value, but they found it stuffed only with old Rags.” Meanwhile, Vizzani’s body was dissected in hopes, we learn, of finding physical proof that Vizzani was actually male or intersex, that is, having both male and female genitalia or reproductive organs, as such proof was thought to explain why they behaved the way they did.

Instead, however, Vizzani is found to have a “normal” female body. At the end of the biography, the surgeon Bianchi proclaims that the other doctors, like himself, “not only discovered her to be a Woman, but also a Virgin, the Hymen being entire without the least Laceration.” His own results confirm that “the Clitoris of this young Woman was not pendulous, nor of any extraordinary Size, as the Account from Rome made it, and as is said, to be that of all those Females, who, among the Greeks, were called Tribades, or who followed the Practices of Sappho; on the contrary, her’s [Vizzani’s] was so far from any unusual Magnitude, that it was not to be ranked among the middle-sized, but the smaller.”

Vizzani has no corporeal markers that explain her turn towards wearing men’s clothes and loving women, such as an enlarged (penis-like) clitoris, or anything else that would mark their body as anything other than female. Vizzani’s intact hymen serves as proof of virginity which, conveniently, makes a saint of them rather than a freak of nature to the Italian populace, or so we are told.

For the English translator, such explanation is not enough. In Cleland’s “needful remarks”, he disavows any kind of sympathy for Vizzani, presenting them as the perpetrator of “odious” and “unnatural” vices, and he criticizes Bianchi for not assigning a mental reason for Vizzani’s behavior. He writes that that “this irregular and violent Inclination, by which this Woman render’d herself infamous, must either proceed from some Error in Nature, or from some Disorder or Perversion in the Imagination.” And since the dissection proves there was no “Error in Nature,” Cleland as editor encourages the readers “to acquit Nature of any Fault in this strange Creature, and to look for the Source of so odious and so unnatural a Vice, only in her Mind.” We can and should take Cleland’s remarks with a large grain of salt. The author of a rather salacious erotic novel himself, his comments on Vizzani may have been exaggerated for the censors–or they may read perfectly in line with his own homophobia and transphobia, given that in Fanny Hill, same-sex relationships are maligned as either inadequate (when between women) or indecent (when between men).

What is striking, to me, though, is that both Cleland and Bianchi appear much more preoccupied with Vizzani’s desire for women than with their gender presentation. Notable, too, is the fact that the women who are attracted to Vizzani warrant very little speculation in this story; in fact, once Vizzani is shot and taken to the hospital, those women fade away from the text. We have to wonder: what did they find attractive about Vizzani?

These issues are central to my new book Sapphic Crossings: Cross-Dressing Women in Eighteenth-Century British Literature, where I consider the role of cross-dressing women in the cultural imagination of this time period. Stories like Vizzani’s were rare, but not unheard of, and newspapers sometimes ran small mentions of odd tidbits like a notice from The Daily Advertiser that detailed a long-term relationship between two servants, a man and woman, who were married for eighteen years: “Some Difference happening between them, the House-keeper declar’d the cook was no Man, but a Woman, and had Reasons to believe that her said pretended Husband was with Child; which we hear upon Examination prov’d so.”

These examples ask us to reconsider the history of sex and gender and, in light of growing discussions about queerness, transness, non-binary genders and pansexuality, to question any pigeonholing of people like Vizzani in the past. In my book, I consider more deeply how transgender identities and same-sex desires were represented through the figure of the female cross-dresser, as well as how eighteenth-century texts represented the women who, overwhelmingly, found the cross-dresser a desirable partner.

Ula Lukszo Klein is Associate Professor and Director of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh. Her book, Sapphic Crossings: Cross-Dressing Women in Eighteenth-Century British Literature (UVA Press, 2021) is now in print and deals with the intersections of gender and sexuality in representations of women who dressed in men’s clothing on the stage and on the page. Her article “Busty Buccaneers and Sapphic Swashbucklers on the High Seas” recently appeared in Transatlantic Women Travelers, 1688-1843 (Bucknell UP 2021), edited by Misty Krueger. She is currently working on an article about transgender citizenship in Aphra Behn’s The Widow Ranter and a book-length project on the concept of queer tourism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. She tweets from @kleinula.

Ula Lukszo Klein is Associate Professor and Director of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh. Her book, Sapphic Crossings: Cross-Dressing Women in Eighteenth-Century British Literature (UVA Press, 2021) is now in print and deals with the intersections of gender and sexuality in representations of women who dressed in men’s clothing on the stage and on the page. Her article “Busty Buccaneers and Sapphic Swashbucklers on the High Seas” recently appeared in Transatlantic Women Travelers, 1688-1843 (Bucknell UP 2021), edited by Misty Krueger. She is currently working on an article about transgender citizenship in Aphra Behn’s The Widow Ranter and a book-length project on the concept of queer tourism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. She tweets from @kleinula.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com