Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt

Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography presents an interdisciplinary examination of trans and genderqueer subjects in medieval hagiography. It demonstrates the importance of such texts as a source for historians of gender and sexuality; in particular, it foregrounds the richness of hagiography as a genre integrally resistant to limiting binaristic categories, including rigid gender binaries. It enables the re-creation of a lineage linking modern trans and genderqueer individuals to their medieval ancestors, providing models of queer identity where much scholarship has insisted there were none, and re-establishing the place of non-normative gender in history.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about?

Alicia Spencer-Hall: Restoring trans and genderqueer histories. Dismantling white-supremacist cis-heteropatriarchy. Spreading trans and genderqueer joy. Doing history better.

Blake Gutt: The book demonstrates that medieval people were analyzing and theorizing gender in a range of complex ways. It shows that identities we would now describe as trans and/or genderqueer have always been thinkable, and thus have always been liveable. Received wisdom tells us that twenty-first century ideas about gender are the most advanced in all ways, the endpoint of a linear development. The common assumption is that, as we look back into the past, we will find that gender roles and gender norms become progressively simpler, narrower, and more binaristic. Trans and Genderqueer Subjects shows that this simply is not the case!

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in trans and genderqueer history, and why did you decide to edit a volume on it? Why did you decide to focus on hagiography?

Spencer-Hall: I stan hagiography, no question. I first encountered these weird, messily sacred texts in undergrad, and I’ve been hooked ever since. For many years, a group of thirteenth-century medieval holy women were my steadfast professional companions. I got up close and personal with them, working on their textual lives for my PhD and first book.

If there’s one thing you learn from hagiography, it’s that identity is an elaborate construction, a performance in which the sense of a stable self is constantly evoked, yet constantly deferred. This goes for gender too. The slipperiness of gender is amped up even more in these texts because of the thorny issue of divinity. The gender binary is a mortal invention. God is beyond gender – or maybe a transcendent amalgam of all genders? – whilst Jesus slides all over the gender map. On the one hand, his body is decisively female, made only of the Virgin Mary’s female flesh. Got it. Yet, he’s also the best human man to ever live. Hmm, OK. And, he’s the best lover – and the best child, the best mother, the best father – everyone, of every gender, has ever had. His wounds appear vaginal; his foreskin is revered as an A+ relic. Frankly, I do not understand how you can read hagiography and not talk about the trans and genderqueer resonances that are right there, in the sources.

Yet, many people – even otherwise progressive scholars who should know better – appear to cling to the cisheteronormative binary framework, refusing to acknowledge – or perhaps being unable to see – what was always already there. At the same time, a lot of transphobic hate is spewed with the veneer of theological justification, including by the Vatican. Such bigoted logic insists that transness is antithetical to holiness, that any transgression of the gender binary signals moral corruption, condemnation not just in the here and now, but forever in the afterlife. Trans and genderqueer people are denied grace.

In the summer of 2016, I was particularly angry at the cishetero-normative status quo. So, I put together a couple of panels on trans and genderqueer hagiography for the following year’s International Medieval Congress, sponsored by the Hagiography Society. The panels were revelatory, electrifying, genuinely awesome. I knew that more people had to witness this joyous, urgent and collaborative intervention. An edited collection was a natural next step, and I recruited Blake as a co-editor. He’s not just a pioneer in medieval trans studies but one of the best thinkers on gender I have ever met. Blake got it immediately, and our vision for what the volume could be, should be, harmonized in the best of ways.

Gutt: Realizing that I was trans, and reading the work of modern trans theorists (not necessarily in that order), transformed my understanding of gender. I realized that I was seeing – and recognizing – things in medieval texts that many cis readers just weren’t. I began to assert in my work that trans perspectives were as valid as cis perspectives in analyzing premodern culture, that trans people have as much right as cis people to claim what feels familiar in medieval texts. The focus on hagiography seemed obvious because there is a significant corpus of saints’ lives featuring protagonists assigned female at birth who become monks. These texts have, until very recently, been read as descriptions of ‘disguised’ women, so readings that emphasized the authenticity of these saints’ transmasculine identities were essential to counter the pervasive transphobic notion that ‘cross-dressing’ is fundamentally deceptive. (Disappointingly, there is a lack of equivalent texts describing protagonists assigned male at birth who become nuns; male gender assignment is questioned and troubled in a number of ways in medieval hagiography, but perhaps not so overtly or extensively, from the point of view of a modern reader.) And, as Alicia points out, sanctity and queer genders just go together in the Middle Ages. The holier an individual was, the less bound they were to the earthly gender binary.

In addition to being an expert on medieval hagiography, Alicia is brilliant at spotting what others don’t, asking questions that shatter assumptions, and recognizing strange and profound resonances between medieval and modern culture, so when they asked me to work with them I jumped at the chance! The experience has been wonderful; I learned such a lot from her, and from each of the volume’s contributors.

NOTCHES: How far do the essays in this volume challenge popular perceptions of gender in the medieval world? Is there one thing that you would particularly like readers (and perhaps especially non-specialists) to learn from this book?

Gutt: As I said above, there is a tendency to imagine that as we look further back in time, we will encounter more and more ‘traditional’ conceptions of gender. However, the sources examined in the volume demonstrate that this is absolutely not the case. The history of gender is not a straight line; gender is a phenomenon that has meant different things in different times and places. Today, the Catholic church is emblematic of religious condemnation of transgender identities; the Vatican’s promotion of ‘human ecology’ is explicitly anti-trans. Yet as Jonah Coman has pointed out, the church’s claims that transness is a modern perversion of divine creation contradicts centuries of theology that embraced queer gender expressions, identities and embodiments, from God who is neither male nor female to the births of Eve from the body of Adam, and Ecclesia, the personification of the church, from Jesus’s side wound. Transness is holy, not just in Europe, and not just in the past – I’m thinking of the Kinnar or Hijra communities of the Indian subcontinent, and of Native American Two-Spirit people. It’s important to acknowledge, too, that European colonizers did their best to eradicate these gender formations.

People we might now describe as trans, non-binary and/or genderqueer have always existed. Not only that, but these individuals have always participated in shaping the times and places in which they lived. Trans people have always mattered.

Spencer-Hall: Everything Blake said, forever. For non-specialist readers, and especially cis readers, I hope the volume shows the flexibility of gender, and the fact that the ‘natural’ – normalized – gender binary is a construct. You don’t have to be a wannabe saint, nor trans or genderqueer, to find affirmative, productive material in the volume which, we hope, will support readers in more fully embracing the authenticity of their own identities, in all their multifaceted glory.

NOTCHES: Blake, your essay focuses on a text which considers ideas about disability and physical impairment alongside transgender embodiment. Can you tell us a little bit about this? And what do you see as the relationship between medieval trans studies and other marginalised histories?

Gutt: In my chapter, I consider the ways that both trans people and disabled people are socially constructed as in need of a cure. These individuals’ existences are often imagined as doubled, haunted by the non-disabled or non-transgender version of themselves that they are ‘supposed’ to be. Just as holiness and transness go together, so too does holiness and disability – some saints prove their sanctity by enacting miraculous cures, while others do so through their own suffering. My chapter examines the interlinking of sacred, transgender, and disabled embodiments through a literary character, Blanchandin·e, who is transformed from female to male by an angel in order to father St Gilles, and then loses an arm in battle, so that the eventual miraculous healing can confirm Gilles’s sanctity.

I work on what I describe as the trans Middle Ages. There are many pasts, just as there are many presents, and developing an underrepresented perspective is always an additive project. Adding a view of the premodern doesn’t mean subsuming or cancelling out other perspectives –– with the exception of the fantasy of a single, neutral, apolitical Middle Ages, which tends to equate to a Middle Ages where only straight, white, able bodyminded, cis European Christian men mattered: and that is one Middle Ages that never existed. I’m proud to contribute to the work of dismantling that singular Middle Ages, to replace it with the trans Middle Ages, and the Black Middle Ages, and the lesbian Middle Ages, and the disabled Middle Ages…. each of which could simply be called ‘the Middle Ages’, and each of which is real and true and valuable.

Spencer-Hall: I’m vigorously nodding my head, as a disabled and genderqueer woman. Intersectionality is key here, absolutely. In our Introduction, for example, we highlight how important feminist and queer scholarship has been in setting the stage for trans medievalist work, alongside its integral limitations. Being a member of a particular marginalized community does not mean that you’re automatically cognizant of the reality of other axes of marginalization. It is essential that we treat other identities with the care and respect that we treat our own. Many people are multiply marginalized. We must do better at recognizing, and holding space for, intersectional identities in the past, and in the present. Otherwise, hierarchies of normativity persist and proliferate, even within marginalized communities.

NOTCHES: What have been the challenges of working on this volume?

Gutt: Terminology can be tricky. It’s important to use language that is respectful to the modern individuals who will see themselves in historical figures or literary characters. And it’s also important to accurately reflect what the texts tell us about the people they describe. Sometimes there aren’t terms, either modern or medieval, that precisely and fully encapsulate complex identities and/or embodiments. In that case, scholars should acknowledge this, and should make clear to the reader what linguistic choices they are making, and why. That’s why we created the Appendix to the volume, the Trans and Genderqueer Studies Terminology, Language, and Usage Guide, which we compiled with the help of the community of trans and genderqueer medievalists and their allies, and which is available for free online.

Spencer-Hall: Pretty frequently, we hear from people who try to ‘gotcha’ us, and trans medievalist work in general, with the contention that using modern terminology is anachronistic. This is not a particularly helpful point, to say the least. We encounter these texts and these subjects as modern people. We are not medieval, and that’s OK. What we can do, however, is ensure that we are not being anachronistic in terms of our treatment of trans and genderqueer identities: to claim that trans and genderqueer people did not exist in history is, in fact, a blatantly modern imposition. Assertions regarding anachronistic use of terminology are not equally applied to all subjects, as James A. Schultz points out. If it’s anachronistic to suggest that medieval people could be trans, then why is it less anachronistic – indeed, ‘historically objective’ – to assume that medieval people were (all) cis, in ways that are identical to modern people? If being trans is anachronistic, why is cis-ness assumed to be coherent, eternal?

NOTCHES: Your introduction raises questions about the relationship between history and activism. How and why should historians engage with activists, in your view? Is writing this sort of history in itself a form of activism?

Spencer-Hall: This is absolutely an activist publication. We have an agenda, and are up front about it. We seek to offer a blueprint for ethical, politicized and urgent work in the field. We aim to uplift above all the voices of trans and genderqueer medievalists. We are insistent upon a return to the sources, to see what they actually say and do, to allow the trans and genderqueer traces within them to breathe anew, released from the suffocating miasma of cisheteropatriarchal normativity. The Usage Guide is a helpful toolkit, true. But it is also intended to enact a certain accountability: scholars now have the tools to do better, and ignorance is no longer a handy excuse.

All history is activism, whether or not you have a precise or even conscious agenda as a historian. This is especially true for people working on the Middle Ages. White supremacists and fascists are weaponizing medieval history to spread hatred and ‘justify’ violence targeting people of colour, and those of us with intersectionally marginalized identities. Remaining ‘neutral’ is not a privilege afforded to everyone equally. The fallacy of neutrality is accessible only to the unmarked subject, an effect of cis-heterosexuality, of whiteness, of able-bodied-ness. History has never actually been objective, it has just been presented to us – the people for whom there was no space in the past, apparently – as such.

Right now, academics of colour are harassed, brigaded, threatened – and more – online, for having the audacity to speak about what is actually in the sources, for showing that racism is endemic in the academy, and particularly the medievalist academy. Scholars are abused along intersectional axes, with misogyny compounding the abuse being hurled at medievalists of colour, for having the temerity to do their job, and to do it well.

In 2017, in the aftermath of Charlottesville, Dorothy Kim wrote: ‘If the medieval past (globally) is being weaponized for the aims of extreme, violent supremacist groups, what are you doing, medievalists, in your classrooms? Because you are the authorities teaching medieval subjects in the classroom, you are, in fact, ideological arms dealers. […] Choose a side. Doing nothing is choosing a side. Denial is choosing a side. […] Neutrality is not an option.’ This holds for all historical scholarship.

Gutt: Everything Alicia said!

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being used in the classroom, and what would you assign with it?

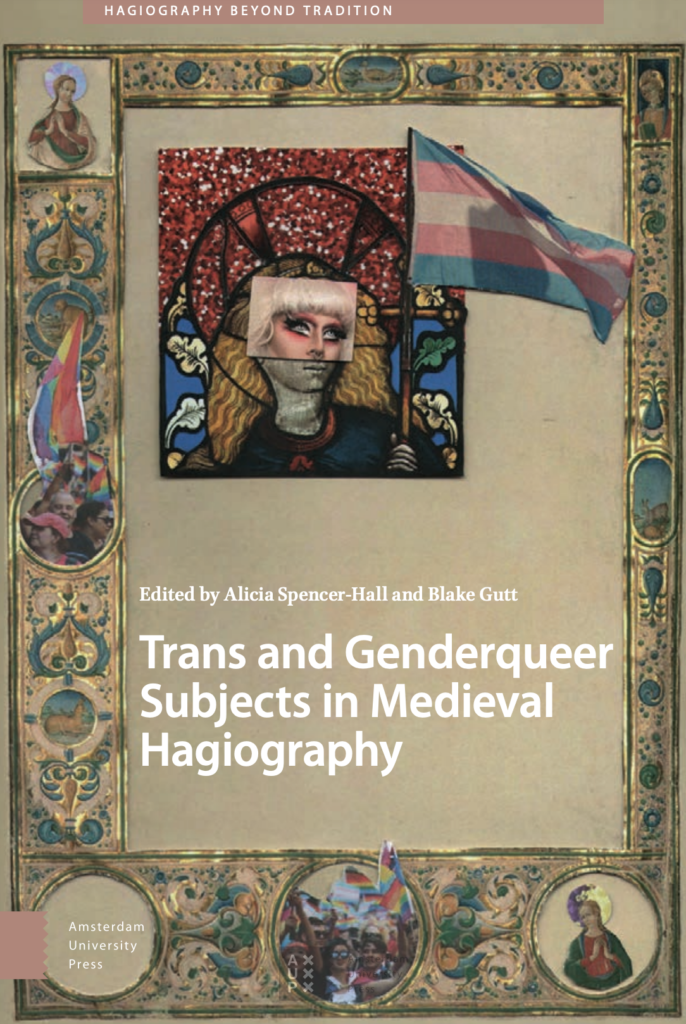

Spencer-Hall: From my perspective, the book has an integral pedagogical value, just by existing in the world. So many people have spoken to us about how much it means to see this kind of scholarship being published, in a ‘legitimate’ format and by a ‘legitimate’ press. The cover art by Jonah Coman is instrumental here, too, I think: equal parts playful and pointed, political and affective. On a macro level, I hope instructors read the volume, and especially the Usage Guide, and consider how they teach gender – medieval and otherwise – and how they might make the classroom an affirming space for trans and genderqueer students. Our editorial Introduction and the Usage Guide would be productive on most syllabi dealing with gender and religion in the Middle Ages. Many chapters in the book explore the purchase the past has on the present, and would be engaging for students in terms of thinking through historiography, not just the role of historians in the production of history but why history matters at all.

In terms of a complementary primary source, for many people, the Life of St Eufrosine is the gateway drug to medieval trans hagiography. One of our contributors, Amy V. Ogden, has recently published a very affordable edition of Eufrosine’s Old French text with an English translation. This is a great resource to introduce students not just to medieval trans hagiography, but hagiography more generally. There’s also a ton of secondary literature on Eufrosine – including in our own volume by Amy and Vanessa Wright – so there’s lots of scope for students to delve into scholarship and broaden their thinking.

Gutt: I just submitted a review of Amy’s fantastic edition of Eufrosine, which is forthcoming in Digital Philology! Another great text to teach alongside our volume would be Jessica A. Boon, Ronald E. Surtz and Nora Weinerth’s edition and translation of Mother Juana de la Cruz’s sermons. Kevin C.A. Elphick writes about Mother Juana’s gender liminality in their chapter in the volume; Juana describes how she was transformed from male to female in the womb at the Virgin Mary’s request. Mother Juana’s sermons expand gendered possibilities; for example, she describes the Father and the Son as simultaneously pregnant with each other in her sermon on the Trinity.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Spencer-Hall: History is never neutral, nor is it inert. Marginalized people are routinely written out of history, and thereby denied the vital resource of lineage, of belonging. It’s not just that such suppression is problematic in a historiographical sense, though it absolutely is. The suppression of marginalized histories does real damage to people alive today. Trans and genderqueer people are routinely told that our existence in the here and now is illegitimate, transitory, illusory. We are aberrant and unnatural, products of postmodern degradation. We embody the ills of the internet age. After all, it’s not like there were trans and genderqueer people before, right? Wrong. Trans and genderqueer people have always been here. We have a history – no, we have histories, plural. We have ancestors, we have roots, our humanity cannot be denied. We have a purchase on history, on humanity itself, that cannot be erased, no matter how hard cisheteronormative historiography tries. ‘We cannot be what we cannot see’, goes the internet saying. This goes not just for contemporary representation, but for historical representation too.

Gutt: I don’t want to suggest that longevity is a prerequisite for validity. However, the long history of identities and embodiments that we would now describe as trans and/or genderqueer constitutes a powerful rebuttal to the repetitive transphobic claims that trans people are some kind of new invention. So much modern fear-mongering about trans existence collapses when we recognize that trans people have always existed, as part of the natural range of human diversity. Medical transition helps some of us come into visibility as who we are, but we’re not a technological invention. Trans and genderqueer identities were being discussed – and more importantly, lived! – long before hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgeries were possible. That’s why trans history is politically urgent in the twenty-first century.

NOTCHES: What are you working on now that this book is published?

Spencer-Hall: I’m finishing up work on my second book, Medieval Twitter, which will be coming out with ARC Humanities in the near-ish future. In it, I unpack the ways in which core features of medieval textuality map onto social media praxes today, alongside doing a deep dive into the community of #MedievalTwitter.

Stickers equal joy, so I thought that giving away some stickers would be a nice way to mark the launch of Trans and Genderqueer Subjects. I put together a trans and genderqueer saints sticker set featuring designs taken from our truly excellent cover image by Jonah Coman, and my own ideas. The response has been so positive that I’m currently setting up a new side-hustle, Sticker Church, your one-stop online emporium for trans-, crip- and queer-affirming medieval-ish arty stickers and postcards.

Gutt: My current research project examines gender transition and transformation in medieval European culture. Alongside literary texts, I’m looking at legal, medical, philosophical and theological constructions of what I broadly describe as ‘non-normative’ gender. I’m also working on my first book, Thinking Shapes, which examines medieval and modern epistemological systems, and how they delimit the shapes and patterns that we give to thought and knowledge.

Alicia Spencer-Hall (she/they) is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her research specialises in comparative analyses of medieval literature and modern critical theory. She works extensively on medieval hagiography with her research inflected by contemporary visual, media, cultural, disability, and gender studies. In all her work, she aims to show what we can learn about our present moment by looking to the medieval past, and what, in turn, we can learn about the medieval era by engaging rigorously, and joyously, with the specificities of the twenty-first century. For example, her first book, Medieval Saints and Modern Screens (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), explores the intersections between divine visions in the lives of medieval holy women and our modern consumption of media. Currently, she is working on a two-volume edited collection on disability and sanctity in the Middle Ages, with Stephanie Grace-Petinos and Leah Pope Parker (Amsterdam University Press), whilst also finishing up the manuscript for her second book, Medieval Twitter (ARC Humanities).

Alicia Spencer-Hall (she/they) is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her research specialises in comparative analyses of medieval literature and modern critical theory. She works extensively on medieval hagiography with her research inflected by contemporary visual, media, cultural, disability, and gender studies. In all her work, she aims to show what we can learn about our present moment by looking to the medieval past, and what, in turn, we can learn about the medieval era by engaging rigorously, and joyously, with the specificities of the twenty-first century. For example, her first book, Medieval Saints and Modern Screens (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), explores the intersections between divine visions in the lives of medieval holy women and our modern consumption of media. Currently, she is working on a two-volume edited collection on disability and sanctity in the Middle Ages, with Stephanie Grace-Petinos and Leah Pope Parker (Amsterdam University Press), whilst also finishing up the manuscript for her second book, Medieval Twitter (ARC Humanities).

Alongside their research activities, Alicia acts as Series Editor for the Hagiography Beyond Tradition series at Amsterdam University Press, and the Premodern Transgressive Literatures series at Medieval Institute. Working as a freelance editor more broadly, they specialize in supporting academic clients for whom English is a second language. Alicia is High Priestess of Sticker Church, blogs about pop culture, critical theory and medieval literature at Medieval, She Wrote, and tweets from @aspencerhall.

Blake Gutt (he/him) is a postdoctoral fellow in the Michigan Society of Fellows (University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, USA). As a scholar of literature, he considers it his job to give people interesting thoughts. His research juxtaposes modern and medieval texts as it engages with the normative systems that shape and restrict thought, and examines how calling these structures into question transforms the ways of thinking and understanding that are available to us. Blake’s current project analyzes medieval representations of gender transition and transformation through the lens of modern queer and trans theory, and traces the lineage between the two, contesting the common assumption that theorization of non-normative gender did not exist in the premodern era. Blake teaches undergraduate courses in modern and medieval French literature and culture. He has published on the trans Middle Ages in Exemplaria, Medieval Feminist Forum, and postmedieval.

Blake Gutt (he/him) is a postdoctoral fellow in the Michigan Society of Fellows (University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, USA). As a scholar of literature, he considers it his job to give people interesting thoughts. His research juxtaposes modern and medieval texts as it engages with the normative systems that shape and restrict thought, and examines how calling these structures into question transforms the ways of thinking and understanding that are available to us. Blake’s current project analyzes medieval representations of gender transition and transformation through the lens of modern queer and trans theory, and traces the lineage between the two, contesting the common assumption that theorization of non-normative gender did not exist in the premodern era. Blake teaches undergraduate courses in modern and medieval French literature and culture. He has published on the trans Middle Ages in Exemplaria, Medieval Feminist Forum, and postmedieval.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com