Charlie Lynch

In May 1974, Leon David Levison preached to the Church of Scotland’s General Assembly in Edinburgh. The Church of Scotland – also known as the Kirk – was at the time Scotland’s largest Christian denomination, a national church adhering to Calvinism. Levison was the Convenor of the Kirk’s Social and Moral Welfare Board. This meant that he occupied a senior leadership position, co-ordinating the activities of a body which administered religious doctrine as well as overseeing the operation of a sprawling network of social services and institutions. Levison held liberal views on some moral issues – for example, he supported the decriminalisation of male homosexuality in Scotland, while according to John Cameron, a former colleague, he was ‘urbane, civilised and never hysteric.’ However, his speech to the General Assembly contained a diatribe against sexual and cultural liberalisation, with the assembled Commissioners being informed that it was: ‘a fundamental truth that sex was for marriage’, for without love, sexual intercourse consisted of a ‘mutual exploitation and despoliation.’ Proponents of premarital sex were pilloried as the ‘trendy and the avant-garde’ who were guilty of ‘leading the young down the path of sexual nihilism.’ He seems to have genuinely feared that the growing acceptance of less formalised intimate relationships and casual encounters might have heralded an impending social collapse.

Statements of this kind were in many ways typical of the conservative Christian backlash against the sexual revolution that took place in Britain in the early 1970s. Moral entrepreneurs such as Mary Whitehouse and Frank Pakenham, Lord Longford attempted to resist and reverse ‘permissiveness’ by appealing to Christian piety. David Levison appears to have been an associate of Longford’s and wrote supportively of the peer’s quixotic attempts to have ‘obscene publications’ banned. David Levison’s own campaigning in Scotland pivoted around attempts to defend premarital sexual abstinence, while at the same time promoting a sacred vision of marriage, which he exalted as the best and only legitimate site for sexual intimacy. Intriguingly, his efforts to create a distinctively Presbyterian response to the heterosexual revolution involved borrowing ideas from liberal Catholicism.

The Kirk’s magazine, ‘Life and Work’ was a staple of middle class homes across Scotland. In 1972, readers were probably surprised to see an article by David Levison which included the provocative sub-heading, ‘Church is Pro-Sex.’ He frankly admitted that earlier Calvinist attitudes and teachings had been too negative and consequently had ‘denigrated the sexual quality of man.’ Instead, the special qualities of sex within marriage would now be promoted as a ‘wonderful gift’ which was ‘the freest and most ecstatic sexual activity, primarily relational and secondarily procreational.’ Such ideas about intimate life acknowledged a debt to those of the liberal Catholic theologian and psychiatrist, Jack Dominian, who argued for the special qualities of sexual intercourse within marriage, asserting that it was ‘the gift through which two people seal privately and publicly their whole self to each other’ and emphasised that it was the supposed devaluing of sexuality’s unique significance which Christians should combat. Consequently, David Levison’s attacks on ‘avant-garde intellectuals’ and the ‘trendy’ (probably meaning followers of sixties counterculture) should be understood as the reverse of his mission to save marriage.

It was no coincidence that such changes in the Church of Scotland’s messaging took place at the close of the 1960s, when the effects of both the heterosexual revolution and secularisation were being felt amongst the youthful population of Lowland Scotland. Religiosity and cultural conservatism declined together, with premarital sexual abstinence diminishing from a powerful cultural norm to a niche religious obsession. Calvinist ideas about sex and intimacy could suddenly seem outmoded, even absurd, to young people. Perhaps recalling a typical experience, John Cameron, then convenor of the Kirk’s Youth and Clubs Comittee, told me how he had been dispatched to speak on the topic of sexual morality to students at Edinburgh College of Art, but remembered their feeling: ‘What you are putting forward is – is quaint – but is of no relevance to us!’ Although art students living in Scotland’s capital city might reasonably be thought to have been at the cutting edge of cultural change, tensions over sex and secularisation bubbled up in more unexpected places such as the industrial town of Falkirk in the Central Belt. Here, a highly localised moral panic erupted in 1969, provoked by anxieties over diminishing rates of church attendance by young people, and fears around teenage sexualities and drug use.

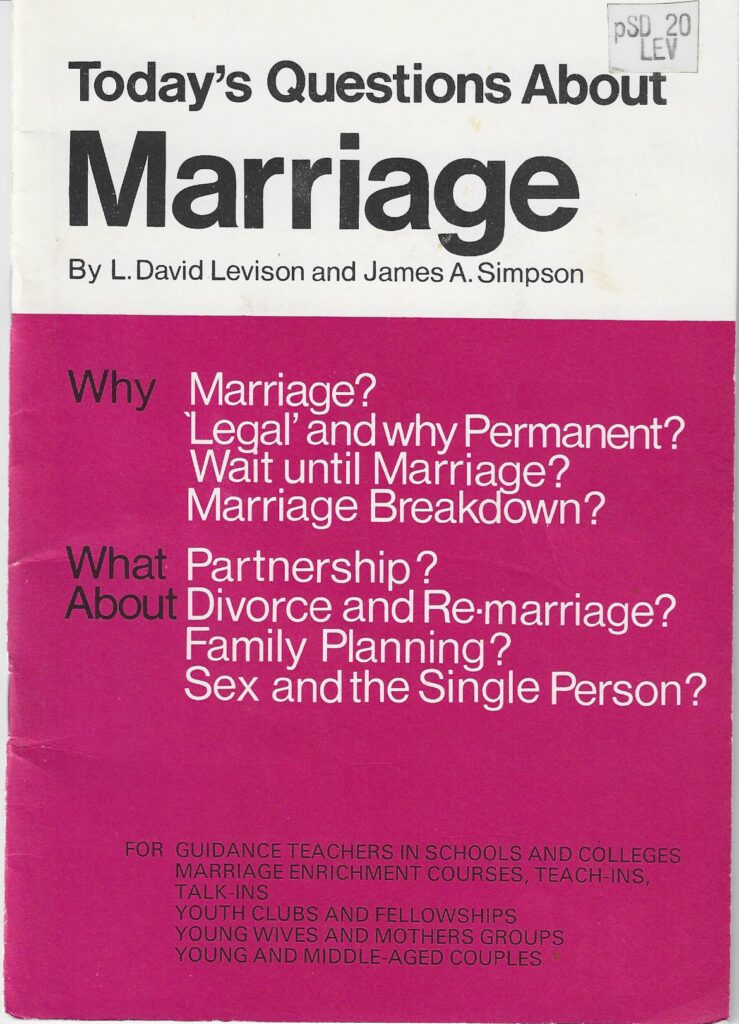

David Levison was correct in his identification of the developments he sought to oppose as products of secularisation. In his 1975 booklet, ‘Today’s Questions About Marriage’ he explained this by recourse to an analogy as revealing as it was disquieting. Writing in character as ‘Dad’ – a concerned father whose son has announced he plans to live with his girlfriend before their marriage – Levison compared society to an enormous medieval cathedral, the walls of which had been supported by flying buttresses in the form of harsh penalties for sexual transgressions. But he considered the number of these ‘buttresses’ had now been reduced by the ‘the pill, abortion and a swing in public opinion.’ Only the ‘inner motivation and strength’ derived from knowledge that the ‘human body and sex’ were ‘divine gifts’ would avert a collapse in the ‘fabric of society.’ By 1975 these ideas were old fashioned and re-emphasising them to an increasingly secular population of young people quixotic. Cameron recalled how the Kirk’s campaign against the spread of premarital sex was in time, ‘quietly put on the back burner.’ By trying to re-emphasise the importance of abstinence from sex before marriage within a rapidly changing cultural climate, David Levison faced a formidable set of challenges that he was ultimately unable to overcome.

Dr Charlie Lynch is a social and cultural historian based at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. Having completed his PhD investigating secularisation and the popular sexual revolution in Scotland during the 1970s, he is working on a monograph. Charlie is co-author (with Profs Callum Brown and David Nash) of The Humanist Movement in Britain (Bloomsbury: Forthcoming) while his journal article, ‘Moral Panic in the Industrial Town: Teenage “Deviancy” and Religious Crisis in Central Scotland’ was recently published in Twentieth Century British History.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com