Moderated by Lina-Maria Murillo, edited by Desiree Abu-Odeh

In 2020, NOTCHES made an explicit commitment to amplify the work of scholars of color and histories of race/racism and sexuality. This roundtable is one piece of the blog’s initiative “Toward an Anti-racist History of Sexuality.” This two-part roundtable brings together scholars who study intermeshed histories of race and racism, sexuality and reproduction, colonialism, eugenics, and fascism to discuss: what can global histories of racial supremacy and reproductive control tell us about our white supremacist present? In Part 1, Lina-Maria Murillo introduces and contextualizes the conversation. Louie Dean Valencia and Asha Nadkarni then discuss how white supremacist ideologies have shaped conversations about demographic changes and immigration, and how those conversations have shaped nationalist and fascist state projects globally.

Part 2 of the roundtable will be published on March 24, 2022.

Lina-Maria Murillo

It is becoming increasingly clear that white supremacy and white power are at the heart of increased voter suppression laws, anti-reproductive justice and anti-abortion legislation, anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ policies, as well as book bans and bills to suppress the accurate teaching of US history and Western civilization across the country.

In the recently published A Field Guide to White Supremacy, editors Kathleen Belew and Ramón Gutiérrez surmise that the January 6 insurrection—and I would argue the entire Trump presidency—reveals how “white power and white supremacy are yet live wires in our politics, in our relationships, and in our conversations with one another.” In the last few months, a US public waited with bated breath for the culmination of three major trials—supposed indictments of the white supremacist violence we’ve seen play out for the last six years. Organizers of the 2017 Unite the Right rally were held liable for $25 million in Charlottesville, Virginia, after the havoc they caused led to the murder of Heather Heyer during the event. Travis McMicheal, Greg McMicheal, and William Bryan, three white men from a suburb in Georgia, were found guilty of felony murder, among other charges, in the brutal 2020 slaying of Ahmaud Arbery. And Kyle Rittenhouse, then 17-year-old vigilante armed with a rifle, was acquitted after he was found not criminally liable for the deaths of two protesters and the injury of another during protests in Kenosha, Wisconsin in support of Jacob Blake, a Black man shot in the back by a police officer in 2020. While some cheered the verdicts in the Charlottesville case and trial of the three white men convicted of killing Mr. Arbery, others believed the Rittenhouse ruling further supports white supremacists’ use of stand-your-ground laws as shields and justifications for white people’s use of deadly force.

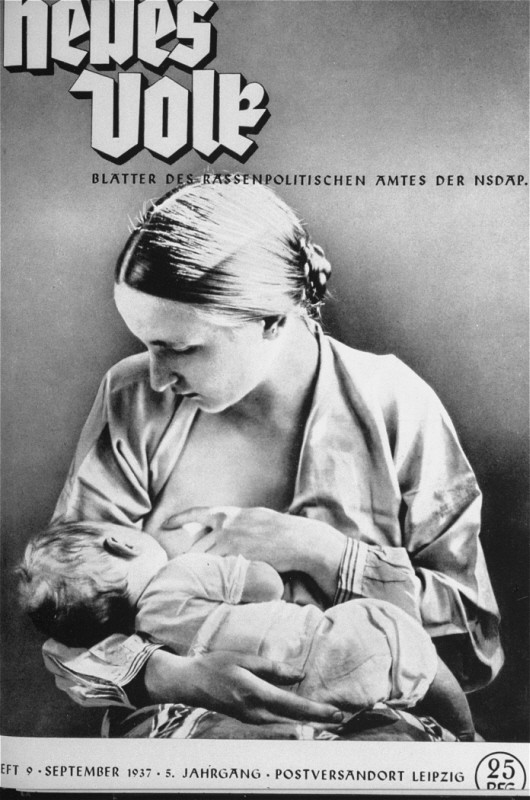

Wikimedia Commons.

Regardless of the outcomes, what’s clear is that the US justice system cannot remand white supremacy. White supremacist ideologies are too deeply rooted in global histories defined by colonialism, imperialism, and neoliberalism. These histories have become flashpoints for conservatives decrying the “indoctrination” of their children under the auspices of critical race theory. Scenes of fired up parents, mostly white, mostly suburban, elbowing their way into school board meetings screaming, ranting, and raving about the evils of teaching their children about the genocide of Indigenous people, slavery, and Jim Crow are emblazoned on our minds. Their rage at confronting historical truths about the origins of racism and white supremacy further kindles their support of white supremacist policies. Dozens of states are passing legislation banning the teaching of critical race theory, conflating this legal framework with basic American history. Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis has gone so far as to advocate policies that prohibit public schools or private businesses from making white people feel “discomfort” when learning about discrimination. This vicious cycle, and the live wires that produced it, has turned into a powerful, political fire ball.

Many argue, and I tend to agree, that the most recent white supremacist aggressions stem from changing demographics—falling white birth rates and rising death rates—as well as the supposed threat of unregulated migration. Barton Gellman’s recent piece in the Atlantic brings the point home with striking statistical figures provided by political scientist Robert Pape and his team at the University of Chicago. Pape’s analysis of demographic data from the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol revealed an underlying influence by the “Great Replacement” theory, a favorite among neo-Nazis and white nationalists in the United States and Europe, suggesting neoliberals the world over seek to “replace” white populations in Europe and the US with brown and Black people from the Global South. Pape found that Trump supporters in areas with greater demographic change were more likely to be part of the insurrection than those living in mostly homogenous, white communities. As Gellman put it, “For every one-point drop in a county’s percentage of non-Hispanic whites from 2015 to 2019, the likelihood of an insurgent hailing from that county increased by 25 percent. This was a strong link, and it held up in every state.”

This brings us to the major themes of our roundtable discussion. Balancing on the precipice of a post-Roe world, with voter suppression and election subversion framing our political future—we’ve asked five reproductive and sexuality studies scholars, whose focus includes histories of Europe, Asia, India, the United States, and Mexico, to opine on this contemporary moment. We asked them to explain how the ideologies of demographic change, sexuality, and reproduction collide at various historical junctures with white supremacy and what these histories can tell us about our present moment.

Contributors examine to what extent white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally. They then explain how those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality. While this is by no means an exhaustive conversation, we do hope it prompts much needed discussions linking the rise of virulent white supremacist violence and the curtailing of civil and human rights for historically marginalized communities. To this end, we asked each scholar to suggest a list for further reading for those interested in learning more about entwined histories of demographic change, racial and ethnic supremacy, and reproductive control.

Louie Dean Valencia

To what extent have white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally?

About ten years ago a racist, dystopian novel came out called The Great Replacement. It soon became a sort of touchstone in radical right circles. The book was shared online on far-right message boards and the like. The book’s author, French antisemitic conspiracy theorist Renaud Camus, has been a proponent of a theory that white Europeans will be “replaced” within Europe due to changing demographics and “open borders.” In a willful misinterpretation of what “genocide” is, he argues that a “white genocide” is taking place through low birthrates amongst white people and so-called “miscegenation.”

Unfortunately, variations of this demographic conspiracy theory go back centuries; migrants and minority groups in Europe have long been targets, especially Jewish and Roma people. More recently, direct references to the so-called Great Replacement theory have been found in the manifestos of right-wing mass shooters in Norway, New Zealand, and Texas. Today, much of this racist discourse about “replacement” has spread across the pond and can be found on widely distributed right-wing news networks, such as Fox News.

This baseless theory is used to legitimate racism and justify policies which amount to ethnic cleansing. For the theory’s proponents, in order to preserve their so-called “white nation,” they must resort to what Alt-Right ideologue Richard Spencer has called “peaceful ethnic cleansing”—calling for policies which would pressure people through policy and blatant racism to “return” to their “homelands.” Spencer is a particularly important figurehead as he was a former collaborator of Stephen Miller, architect of Donald Trump’s immigration policy, when both were at Duke University. “Peaceful ethnic cleansing” is as illogical and disgusting as it sounds, but has potentially shaped the US’s own immigration policies during Trump’s presidency.

The truth of the matter is that one of the few things that humans have always done is migrate—we’ve always been on the move. In fact, much of these demographic changes that concern white nationalists are a legacy of European colonization and the postcolonial, global world we now live in.

How have those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality?

To virtually no one’s surprise, questions of sexuality and racism have long intersected historically. I always try to define fascism simply; it is idealization of one dominant group, extreme racialized nationalism tied to that ideal, and extreme institutionalized oppression of all non-conforming groups. It is racism + misogyny + anti-liberalism + classism + ethnocentrism + ableism + queerphobia + xenophobia + nationalism. Most frequently, it is tied to antisemitism. While each case of fascism has its own variations, we see these elements in all fascism. Other fascist tendencies—concentration camps, attempts to use the past to legitimate a fascist future, violence, its aestheticism, and all the other hallmarks we might recognize—are all dependent upon how much power fascism has, or is attempting to claim for itself. Fascist ideologies and tendencies often lay in waiting even in democratic countries. In northern Europe, for example, there were eugenic projects going all the way into the 1970s that were meant to essentially breed people based on desired features.

Most infamously, the concept of eugenics reached its fevered pitch during the fascist regimes of the early twentieth century. Fascism has a long history of regulating the bodies of women and queer people. Fascism, in particular, relies on a belief that one must dedicate one’s life and energy to the nation. For example, in Nazi Germany, women were given medallions for having children and encouraged to have more. People’s facial and physiological features were measured and compared—a pseudoscience built around a desire to breed “undesirable” features out of people. In this sense, at its core, fascism attempts to produce “purity.” But instead, really, in that reproduction of purity, it promotes genetic homogeneity. Taken to its most logical extreme, fascism is an ideology that can only end with inbreeding. Diversity is then not just a social good or progressive end in itself, but a rebuttal to fascism’s logical end as well.

In fascist nations, those not producing children [for the nation], including queer people or people who didn’t fit some imagined ideal, were often at risk of sterilization. Queer people, regarded as “degenerates” by fascists, are an ever-present threat to fascism. They threaten the patriarchy and traditionalists. It’s important to note that the books burned in some of the best-known photographs of book burnings in Nazi Germany were from Magnus Hirschfeld’s sex institute that argued for human rights for queer people and gender non-conforming people in the early twentieth century. Fascism often emerges as a reaction to moments when women and queer people attempt to claim power for themselves in society.

Part of the goal of this roundtable is to bring together historians focusing on the intersecting themes mentioned above. For those in our audience who are interested in learning more or teaching this history, could you recommend one or two key texts to better understand the material presented here?

I’m a big fan of Victoria de Grazia’s work, particularly her book How Fascism Ruled Women. I’d also recommend Sex after Fascism by Dagmar Herzog. Lorenzo Benadusi’s The Enemy of the New Man: Homosexuality in Fascist Italy is also an important read. If I can indulge in a bit of self-promotion, I’d recommend my edited volume Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories, for more on the Great Replacement theory and contemporary fascist and far-right groups. I’d also recommend José Pedro Zúquete’s The Identitarians: The Movement against Globalism and Islam in Europe.

Asha Nadkarni

To what extent have white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally?

My first example is particularly resonant given the upsurge of violence against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic: that is, the linked ideas of “race suicide” and the “yellow peril” in the United States around the turn of the twentieth century. The term “race suicide” was coined in 1901 by sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross and popularized in a 1905 speech by Theodore Roosevelt. It pitted the declining birthrates of “native” (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) Americans of “good stock” against the fecundity of immigrants. Specifically, Ross evoked the idea of the “yellow peril” to assert that while white Americans will only have as many children as will allow them to maintain their standard of living, Chinese immigrants will have more children due to having a lower standard of living. Through this mechanism, Ross argued, “the American farm hand, mechanic and operative might wither away before the heavy influx of a prolific race from the Orient” unless “native” Americans take their reproductive duty in hand. Of course, the threat of the “yellow peril” was not just a reproductive one but was also associated with the idea that Asian bodies were unclean vectors of biological and moral contagions.

Jumping forward over half a century, the fecundity of yellow, brown, and Black bodies was similarly targeted by the discourse of overpopulation. The infamous opening of Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s 1968 The Population Bomb, where the authors find themselves traveling by taxi through a “crowded slum area” in Delhi and are “frightened” by the “people, people, people, people” that surround them, borrows on a similar vocabulary of inundation. While this scene is meant to prompt readers from the Global North to act for their “less fortunate fellows on Spaceship Earth,” the problem is nonetheless located firmly within the Global South. I take up these two disparate examples to point out the ways that positive eugenics (more reproduction by certain groups) and negative eugenics (less reproduction by others) are employed in each case. Those fearing “race suicide” implored white Americans to do their reproductive duty (a message which conveniently dovetails with antifeminist desires to keep women in the home), while those fearing the “population bomb” advocated population control in the Global South. Even though the “population problem” has been thoroughly debunked, rhetoric around overpopulation persists to this day in the casual eugenic discourse surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic.

How have those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality?

Returning to the Asian American example, turn-of-the-twentieth-century Anglo-American fears of “race suicide” were expressed through a series of Asian exclusion acts intended to keep Asians from US shores. These laws were often expressly sexualized – for instance, the 1875 Page Act denied entry to “any subject of China, Japan, or any Oriental country” being brought to the United States for “lewd and immoral purposes.” Relying upon prevailing stereotypes about Asian women as prostitutes and carriers of venereal disease, this Act codified the anti-Chinese rhetoric of the moment into immigration law.

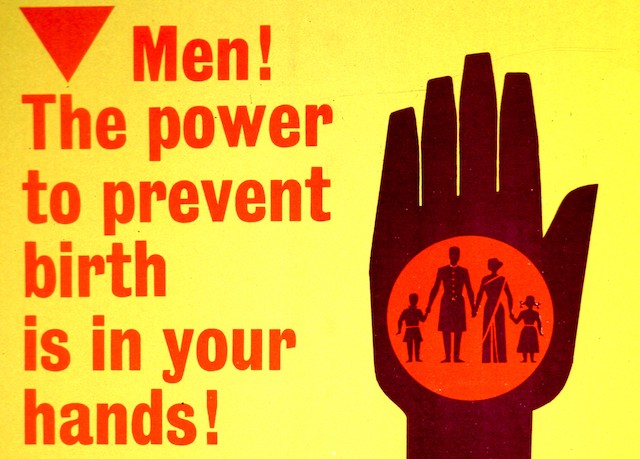

While immigration exclusion was one of the forms US eugenics took, in pre-Independence India the eugenic movement was largely concerned with birth control education and right reproduction as a charge of the incipient nation. After independence in 1947, however, the global discourse of the “population problem” took root in terms of Indian national priorities. In 1951 India was the first country to launch a government program centered on controlling population (the National Family Planning Programme) and in 1953 began the Khanna Study – a population control experiment launched in collaboration with the Harvard School of Public Health and the Rockefeller Foundation. These examples speak to India as the test site for population experiments both by its own government and international bodies. These experiments reached their apex during Indira Gandhi’s premiership, culminating in the abuses of mass sterilization during the period of her Emergency rule (1975-1977). While a series of incentives and disincentives for sterilization had existed in India since the late 1950s, during the Emergency these efforts, at the behest of Gandhi’s son, Sanjay Gandhi, were expanded to include compulsory sterilization programs, which often operated in concert with slum clearance programs.

What is key to remember here is that even if the concern about population size seems a general metric, in fact the population “problem” was always aimed at minorities and the poor. If for the Global North the “population bomb” was an incendiary located in an undifferentiated Global South, for the Indian government negative eugenics was aimed at very specific groups. Nonetheless, India’s programs were also in response to pressure from the United States and the international community: in the mid-1960s US President Lyndon Johnson linked food aid to India to the enforcement of family planning policies. And despite the documented human rights abuses by Indira Gandhi, she won a population prize from the United Nations in 1983.

Part of the goal of this roundtable is to bring together historians focusing on the intersecting themes mentioned above. For those in our audience who are interested in learning more or teaching this history, could you recommend one or two key texts to better understand the material presented here?

Betsy Hartmann’s classic text, Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control, remains a key work on the topic of reproduction and reproductive control. Originally published in 1987, it is currently in a third edition with a new preface by Hartmann written in 2016. It is critical for how it explodes the notion of the population problem and exposes the ways in which the false Malthusianism of overpopulation discourse has become a weapon to be wielded against the poor and underprivileged. A somewhat more recent book that I’ve also found helpful is Matthew Connelly’s 2008 Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. I appreciate the global scope of this book and the care with which Connelly connects the many different parts of the web of eugenic and overpopulation discourse throughout the twentieth century. I found both of these works incredibly helpful when writing Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India.

Lina-Maria Murillo is an Assistant Professor of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, History, and Latina/o/x Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Fighting for Control: Power, Reproductive Care, and Race in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (UNC Press). She examines the tensions between advocates for population control and those committed to greater reproductive access for the majority Mexican-origin women in the borderlands. She tweets from @LinaMariaMuril6

Lina-Maria Murillo is an Assistant Professor of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, History, and Latina/o/x Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Fighting for Control: Power, Reproductive Care, and Race in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (UNC Press). She examines the tensions between advocates for population control and those committed to greater reproductive access for the majority Mexican-origin women in the borderlands. She tweets from @LinaMariaMuril6

Louie Dean Valencia is an Assistant Professor of Digital History at Texas State University. He is the author of Antiauthoritarian Youth Culture in Francoist Spain: Clashing with Fascism (Bloomsbury, 2018) and the editor of Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories (Routledge, 2020). His research focuses on the history of European countercultures and their intersections with fascism, antifascism, queer people, youth, and urban studies. He tweets from @BurntCitrus

Asha Nadkarni is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where she teaches courses in postcolonial studies, Asian American studies, and transnational feminism. She is the author of Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), and co-editor (with Cathy Schlund-Vials) of Asian American Literature in Transition, 1965-1996: Volume Three (Cambridge University Press, 2021). She is currently working on a second book project, tentatively titled From Opium to Outsourcing, that focuses on representations of South Asian labor in a global context.

Desiree Abu-Odeh recently earned her PhD in Sociomedical Sciences from Columbia University, where she focused on the history and ethics of public health. Her dissertation examines the emergence of what is now known as “sexual violence” and responses to it on American college campuses from 1952 to 1980. Her research interests include histories of gender, race, sexuality, and social movements in the United States. Her work has been published in Social Science History, American Journal of Public Health, and Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com