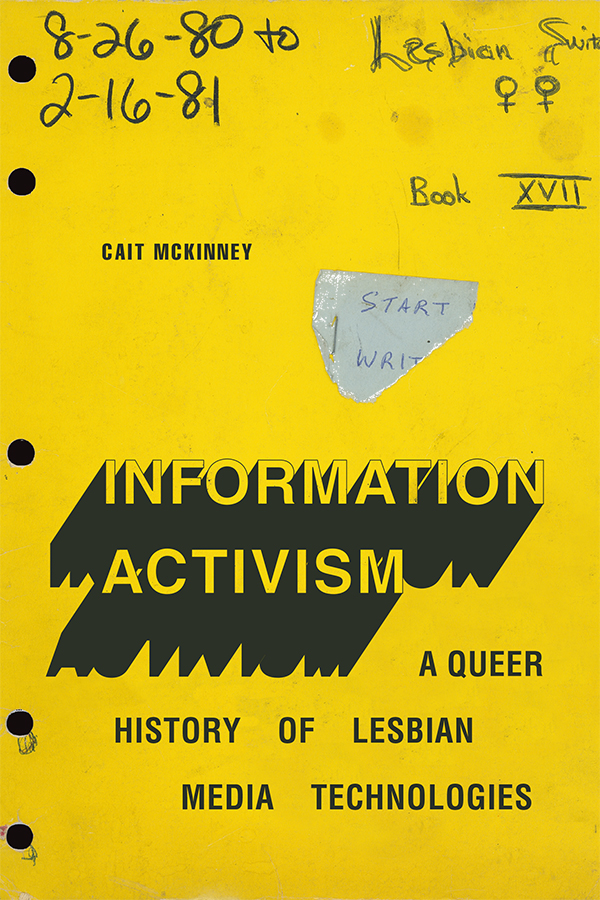

Cait McKinney

For decades, lesbian feminists across the US and Canada have created information to build movements and survive in a world that doesn’t want them. In Information Activism, Cait McKinney traces how these women developed communication networks, databases, and digital archives that formed the foundation for their work. Often learning on the fly and using everything from index cards to computers, these activists brought people and their visions of justice together to organize, store, and provide access to information. Focusing on the transition from paper to digital-based archival techniques from the 1970s to the present, McKinney shows how media technologies animate the collective and unspectacular labor that sustains social movements, including their antiracist and trans-inclusive endeavors. By bringing sexuality studies to bear on media history, McKinney demonstrates how groups with precarious access to control over information create their own innovative and resourceful techniques for generating and sharing knowledge.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

Cait McKinney: Information Activism is about the ways lesbian feminists in the 1980s and 1990s took up new media technologies to build their movements, connect with each other, and make life more liveable for queer women. I look at a range of technologies, specifically newsletters, telephone hotlines, indexes and bibliographies, computer databases, and digital archives. I put forward the concept information activism to describe the confluence of people situated in collectives, their visions of justice, and the practical, everyday work they do with information technologies. People will want to read the book if they’re interested in alternative media histories, queer archives and their strategies, or are just fans of queer and feminist history.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what questions do you still have?

CM: When I started this research, I set out to learn more about how lesbian community archives have responded to the pull towards digitization over the last fifteen years. How did they understand issues like the accessibility of digitization technologies (how hard they are to use, what they cost), privacy (how they decide what can be made available online and what can’t), data governance and description (where they store digital objects and how those objects are categorized). I thought that lesbian feminist politics might have a lot to teach us about the politics of digital information, and it does! The project needed to get bigger though—I realized that lesbian feminists had a long history of thinking about these same problems through older media, like paper newsletters. So the work became wider in its scope to draw a more complete picture of lesbian feminism and information.

NOTCHES: This book engages with histories of sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

CM: This a sexuality studies book about something we often imagine to be deeply unsexy: information. I hope that the book offers readers ways to think about how media, information, and technology factor in the ways histories of sexuality are created, archived, and re-encountered. The stories in the book showcase how librarians, archivists, indexers, and other amateur and professional information workers build and sustaining sexual cultures—and we often don’t give these folks enough credit or attention when we write histories of sexuality.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use? Were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

CM: I drew primarily on LGBTQ+ community archives to do this research: The Lesbian Herstory Archives (New York), The ArQuives (Toronto), and The LGBT Community Center National History Archive (New York) were the main ones. I was able to draw on collections that documented the everyday, behind-the-scenes work of lesbian feminist activist groups who were focused on sharing information. For example, at the Center Archives, I worked with The Lesbian Switchboard of New York’s collection, which included paper call logs for every telephone call answered at this information and support hotline over thirty years. When I could, I also supplemented this archival research with interviews with activists and archivists. One challenge was that the often very technical or bureaucratic decisions that mattered to me, questions like “how did you choose that particular computer”, didn’t necessarily register as being important enough for these folks to remember 40 years later (totally fair!). But the interviews were crucial for understanding what motivated information activists to do their work, and the bigger affective dimensions of working with information.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

CM: One challenge that any digital history project faces is that work with digital technologies can be quite ephemeral. As a researcher, my dream would be able to actually play around with the first website that an organization created in the early 1990s—but generally what remains are just printouts or stories that I’m left to make sense of. This is also a deeply North American book, which reflects my situatedness and my training. All books have a scope and a geography, but as a reader, I’m also interested in reading transnational histories of media.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

CM: I’ve been lucky to get the chance to talk to students in media studies, information studies, and gender and sexuality studies about the book and the conversations I’ve had in those contexts have all been different. Those are the main places I see the book being taught. I’ve actually created a short teaching video and guide here, which was meant to ease the burdens of online pandemic teaching for others, but I think it’s still useful.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

CM: I’ve got two new projects on the go, one with Dylan Mulvin at the LSE about the relationship between HIV/AIDS and computing in the 1990s. And I’m working on a new book called The Sex Lives of Data, which is an exploration of how concepts from sex and intimacy have shaped how we understand digital technologies since the 1960s. To give you a better idea of what that means, the chapter I’m working on now is about how the concept of attachment from affect theory can help us historicize email attachment as a new genre of communication in the 1990s.

Cait McKinney is Assistant Professor in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. They are the author of Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies (Duke 2020), winner of the Gertrude Robinson Best Book Prize from the Canadian Communication Association and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist for LGBTQ studies. They co-edited Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and other Lesbian Hauntings (UBC, 2019), and a 2020 special issue of First Monday on HIV/AIDS and Digital Media. They tweet from @caitmckinney

Cait McKinney is Assistant Professor in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. They are the author of Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies (Duke 2020), winner of the Gertrude Robinson Best Book Prize from the Canadian Communication Association and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist for LGBTQ studies. They co-edited Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and other Lesbian Hauntings (UBC, 2019), and a 2020 special issue of First Monday on HIV/AIDS and Digital Media. They tweet from @caitmckinney

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com