Michael Rosenfeld and William A. Peniston

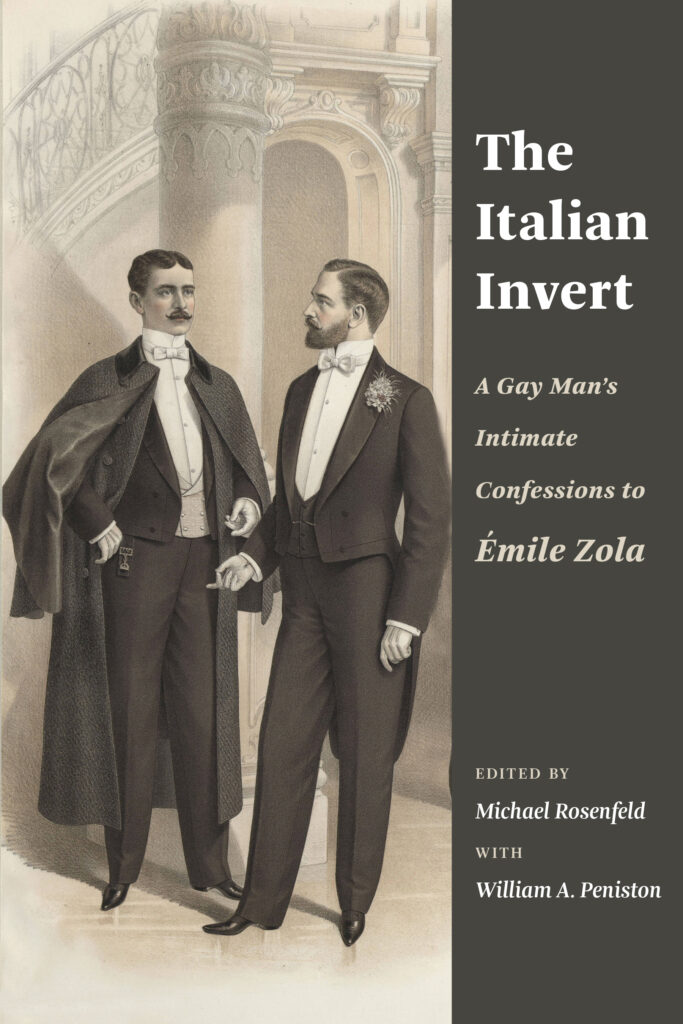

The Italian Invert is a unique series of letters, sent by a 23-year-old dashing young Italian aristocrat to novelist Émile Zola in 1888 or 1889 and to doctor Georges Saint-Paul in 1896. In these revealing letters, the Italian made an astonishing confession, frankly describing his sexual experiences with other men as well as his “extraordinary” personality. Zola judged them too controversial to use and gave them to Saint-Paul, a young doctor, who published a censored version in 1896 in a medical study on sexual inversion, as love between men was then known. When the Italian came across this book right after its publication, he was shocked to discover how his life story had been distorted. In protest, he wrote a long, daring, and unapologetic letter to the doctor defending his right to love and live as he saw fit. This book is the first complete, unexpurgated version in English of this remarkable queer autobiography.

NOTCHES: Why will people want to read your book?

Michael Rosenfeld: The book presents a rare first-person “confession” of queerness at the end of the nineteenth century. The author reveals himself in beautiful prose and shares his hesitations, his desires, and finally how he satisfies his sexuality. It is also a coming-of-age tale, as the reader can follow the evolution of the Italian’s awareness of his queer love, thus presenting a unique point of view for that time, where most texts are framed by medical discourse or hidden behind a literary smokescreen.

William Peniston: The story is engaging in and of itself for its human-interest elements, but it is also a counterpoint to the concentration on the trials of Oscar Wilde and the lives of other famous men, who have received so much attention from historians of homosexuality. The history of gay sex and gay relationships in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is far more complex and varied than we have hitherto imagined.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what questions do you still have?

WP: I first came across this story in an abbreviated form and found the first letter – which culminates with his love affair with the sergeant in his military regiment – extremely romantic. I was then shocked to read the second letter – which is about his seduction as a teenager by one of his father’s friends – in another longer, but still censored version. The new discoveries from the 2010s – which Michael will discuss further on – have taught me that this man is a far more complicated individual than I had initially thought – and he is still fascinating!

MR: I discovered this text as I was preparing my Master’s in 2001 about “unconventional sexuality” in Zola’s prose and saw that he had written a preface to a medical book about “Perversions and perversities”. Like William, I read the censored versions of the text and wondered if a manuscript existed. As they say, the rest is history.

NOTCHES: This book engages with histories of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

MR: The Italian’s story is about self-perception: how does a young educated queer man slowly realize he loves men, and then how does he discover he is not alone in the world? Through his letters, we get an idea of the information available to someone who wants to expand his knowledge about “pederasty” and “sexual inversion”, as they were called at the time. More interestingly, it also allows us to see how he adopts these historical, literary and medical sources to his own desires. In addition, in the introduction, we study a number of letters sent by queer men to Saint-Paul between 1896 and 1920, which show how they relate to the Italian’s story and compare him to themselves, once again seeking understanding and legitimization of their love.

WP: The Italian man’s story raises uncomfortable questions about the relationship between class, race, ethnicity, and sexuality, not to mention sex and gender, religion and politics, art and literature, and other topics.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book?

MR: In November 2014, Alain Pagès, the (then) director of the Zola research centre in Paris told me about his 2011 discovery of the manuscript of the 1896 letter the Italian sent Dr. Saint-Paul, which is in the Zola family archives, and he invited me to publish it.

I then contacted one of Saint-Paul’s grandsons, and asked if they kept any documents from the doctor and he confirmed they did. In 2016 I visited these archives and made a number of fascinating discoveries:

- A fragment from one of the letters sent to Zola in 1889, which the doctor had cut out, with writing on both sides. This fragment allows us to confirm that the author of the letters to Zola and of the letter to Saint-Paul is the same person.

- A five-page long document in which Georges Saint-Paul lists the “parts of the Novel of an Invert that had to be removed”, allowing us to reinstate these censored parts into the existing text. For the first time in 120 years, the Italian’s testimony is complete, and the French text was published in 2017.

One major challenge we faced was the state of some of the documents, which have not been preserved in good conditions and had deteriorated. The Italian’s handwriting is also sometimes hard to decipher, especially on the last pages of the 1896 letter to Saint-Paul, where his writes becomes smaller and smaller, as he strives to fill the pages.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

WP: As a graduate student, I read H. Stuart Hughes’s book, Consciousness and Society, on the reorientation of European social thought at the turn of the 20th century. I was particularly intrigued by the generation of 1905, which included André Gide, Marcel Proust, and Thomas Mann, who were beginning to deal with issues of sexuality in their novels. Later, I wrote a dissertation on the male homosexual subculture of Paris in the 1870s based on police arrests for “offences against decency”. It was only natural, I suppose, that my second project was a translation of eight queer autobiographies from nineteenth-century France, one of which was this one by the Italian “Invert”. At the time, my colleague Nancy Erber and I had available to us only the censored versions that the doctor had published in 1896, 1910, and 1930. Consequently, we were both thrilled when Michael Rosenfeld asked us to collaborate with him on this version based on the new discoveries in the archives.

MR: During my B.A. studies in French literature at Tel-Aviv University in 1995-1998, I took a seminar on Zola as a representative of a new modern form of literature, which reflects society accurately. I was struck that sexuality appeared so freely in his novels and that he also showed a lot of “different” kinds of love, including queer love. I also started attending one of the first “queer theory” reading groups at Tel-Aviv University, directed by Prof. Aeyal Gross at the time, which had a strong sociological focus, but also discussed queerness in a wide variety of disciplines. I remember we read Judith Butler and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and then some Foucault, too. So I decided to apply these theories to Zola’s novels.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

WP: I have spent my career as a librarian in a museum, far outside the classroom, so I will let Michael answer this question.

MR: The Italian’s testimony fascinates students – both queer and normative ones – as they have a warped image of queer people in the nineteenth century seeking love in a hidden way, in dark alleyways and using codes and winks. Of course, those situations did exist at the time, but this testimony allows them to see an alternative and quite positive — sex-positive — narrative, which is open, clear and direct. His testimony gives a rather unique perspective on queer cruising, seduction techniques, and even practical tips for pleasure. It is a rich text that allows lecturers to assign a choice of fragments on specific topics and show how these were seen at the time. For example, I have been giving an invited lecture at a “History of the Body” seminar for a couple of years now, and I assign fragments of the book that show how the Italian sees his body and gender identities. Students have repeatedly told me they identify with the Italian’s narrative and that they share some of his experiences.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

WP: Today, with our ever-expanding understanding of sexual identities and their fluidities, the Italian man’s search for his own self-awareness still resonates with LGBTQ people and their allies. His journey from a position of loneliness and isolation at the age of 23 to one of acceptance and pride at the age of 30 is both instructive and encouraging. Along the way, we can enjoy his narratives of family antecedents, childhood memories, and adolescent experimentations, as well as his love affairs and his sexual adventures. We may not always like him, but we cannot help but admire his courage and his joie-de-vivre.

MR: I also believe it is an important example of “queerness over the ages” as it contradicts the narrative we can read in conservative circles that “homosexuality was invented in the 1950’s”. The Italian’s defense of queer love is the perfect counter-example to the current denial of queer rights in Italy and elsewhere.

WP: One literary critic (Colton Valentine) noted in a recent article in The Drift that this queer autobiography was an antidote to the “queer presentism” that is so prevalent in gay literature today. He thinks that we should know more about the queer past before we try to reinvent or reimagine it. He suggests that we need new editions or translations of gay and lesbian stories from the past, such as Abel Hermant’s Le Disciple aimé (1895) or Achille Essebac’s Dédé (1901). Perhaps the translation of one of these forgotten novels should be my next project.

MR: I am currently adapting my thesis about queer love in French and Belgian literary and public discourse between 1870 and 1905 for a book. In addition, together with my colleague Clive Thomson, we are finalizing the correspondence between Paul Bourget, Adrien Juvigny, Georges Hérelle, Maurice Bouchor and Félix Bourget from 1869 to 1873. In these 291 letters, these young adults discuss their queerness, their love for their classmates, and the historical and literary references they seek to justify their desires. They are also among the very rare testimonies of queer sexuality in high school at the end of the Second Empire and the start of the Third Republic in France.

Michael Rosenfeld is a junior FWO postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Literary and Intermedial Crossings at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. His current project analyses how queer intellectuals in France, Belgium and the Netherlands collaborated to legitimize same-sex love in their writings between 1885 and 1910. His research focuses fin-de-siècle French and Belgian literature and authors, such as Émile Zola, Jean Lorrain, Georges Eekhoud, and Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, as well as the representations of queer love in literature and ego documents in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Michael Rosenfeld published Confessions d’un homosexuel à Émile Zola in 2017, which was published in English by Columbia University Press in 2022 under the title: The Italian Invert: A Gay Man’s Intimate Confessions to Émile Zola and in Spanish in April 2023 as Así nací, así moriré. Confesiones íntimas de un homosexual a Émile Zola. He has published articles in journals, such as Nineteenth Century French Studies, Dix-Neuf, Littératures, and Les Cahiers naturalistes, and has contributed essays to several collected volumes.

William A. Peniston is the librarian and archivist emeritus at the Newark Museum of Art. He is also a historian of France, the author of Pederasts and Others: Urban Culture and Sexual Identity in Nineteenth-Century Paris and the co-editor and co-translation, along with Nancy Erber, of Queer Lives: Men’s Autobiographies from Nineteenth-Century France, among other works.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com