Jessica Gregory

In 1894 numerous suspicious classified advertisements in popular newspapers were reported to the Home Office for the attention of the Minister. These insignificant and seemingly innocuous advertisements consisted of a couple of lines of text, a contact address and little else. They became a locus of consternation and anxiety, however, for both local and national government as a wider scandal over their meaning and intention erupted.

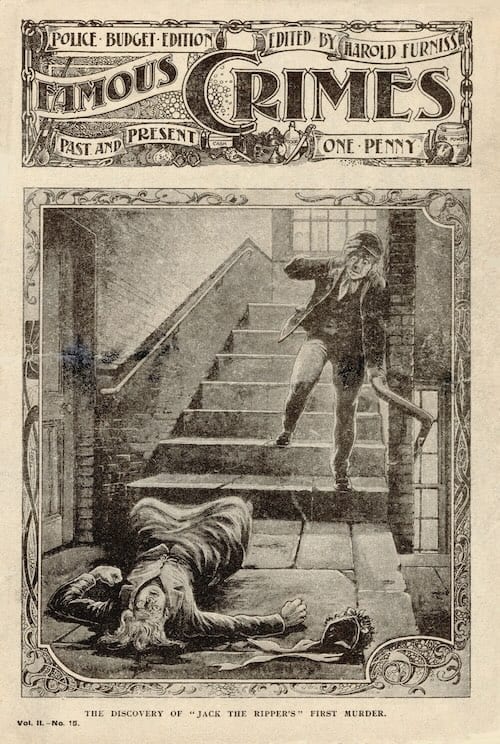

The scandal of the massage houses had followed on from earlier controversies over the nature and prevalence of sex work in Victorian society. Most significantly, W. T. Stead’s sensationalised exposés of sex work, trafficking and child exploitation in London aroused both public interest and anxiety. Authorities’ concerns about the prevalence of such vice was soon addressed through the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885. The hysteria over the ‘vice’ of sex work would be further escalated with the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888. By the 1890s, the anxiety over sexual immorality and its consequences was a well-established social concern to both the government and general public.

The emergence of another scandal based on the supposed misuse of therapeutic treatments as a cover for sex work reflected the changing orientations of a service under pressure. With sex work under intense legal and social scrutiny, it had to operate in more discrete ways. Sex workers, it was believed, were utilising a grey space between the fields of legitimate medical practice and commercial health enterprises to hide their service under the guise of therapeutics.

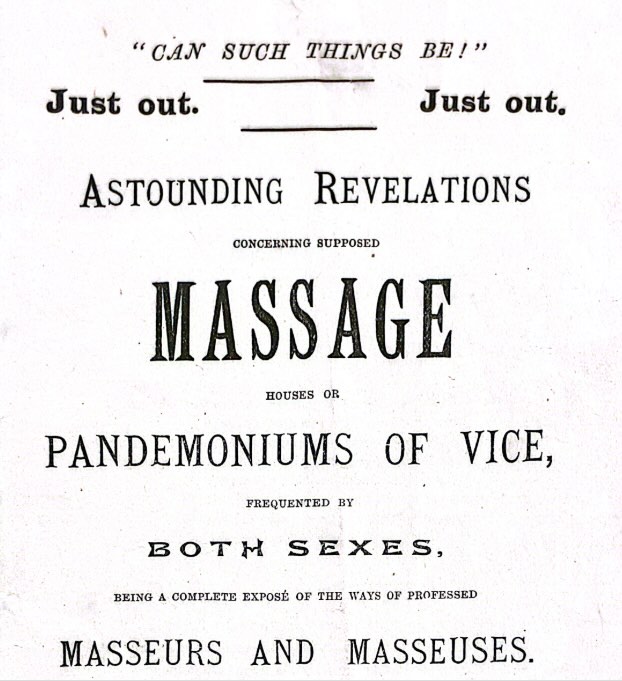

In the 1890s, massage therapy was being newly popularised as a commercial treatment option with several publications on the subject appearing in the 1880s. The emergence of numerous massage shops throughout London that were largely unmediated and involved nudity and touch within a private space produced concern over their respectability. The association between massage and the sensual, and consequently sexual touch, drove forward the concerns of the medical profession that the commercial massage parlour was simply a front for sex work. The promotion of such services via classified advertisements in newspapers and journals worried authorities because they enabled a wide and unbiased appeal to many more people than street-based solicitation could ever produce.

Given the controversies over sex work in the 1890s and the many penalties it could provoke, advertising sex work openly was not an option for those running brothels. Instead, their advertisements were disguised through tactics of euphemism or mimicry of other services. The representation of sex work through coded advertisements could provide business opportunity for the business/seller/worker. At the same time, if authorities could de-code such productions they could trace and prosecute those they thought in contravention of the law.

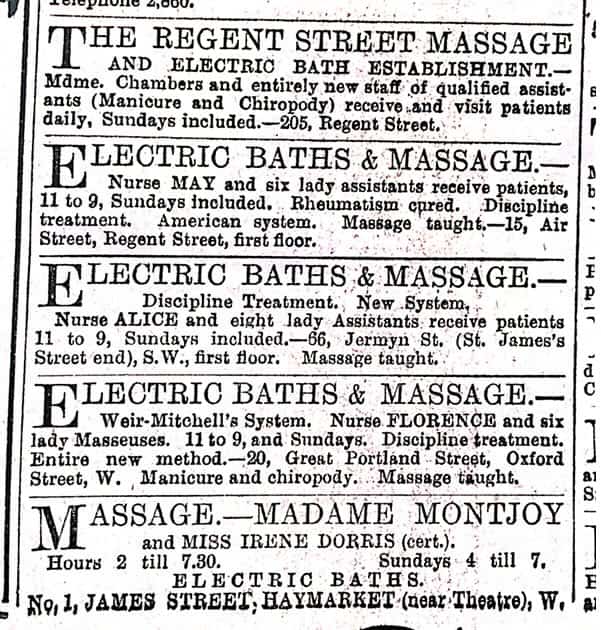

The advertisements in question appeared in various papers such as Society Magazine, Pelican Magazine, The Sporting Times, The Morning Post and others. They often advertised under a massage business name or therapeutic treatment with an address and a reference to a proprietress, usually a Madame or Mademoiselle, and a few nurse assistants. Often these advertisements would reference their nurses by name and age, promoting the youth of female assistants. Other clues to their intentions included references to late opening times and a ‘discrete’ service.

Police collected examples of questionable advertisements in their efforts to identify brothels. One was an advertisement in the Daily Telegraph for massage at 4 Rupert Street. The business was run by a Mademoiselle Georgette, aided by a number of nurses. Police seemed to confirm the character of the business when they visited. The police report described its lavish décor and the discovery of birch rods as evidence of its real intentions.

Similar descriptions of massage houses were provided by anti-vice societies who interviewed former employees. They suggested through their testimony that a range of sexual services might take place in different establishments, with some catering to more specific tastes. A case recorded by the Association of Moral and Social Hygiene notes one woman who provided her own ‘instruments’ of whips, birches, canes, rawhide, thongs, straps, etc. In addition, T. Skeat’s (perhaps sensationalised) pamphlet on the scandals references women frequenting dubious massage establishments to see young men, ‘apparently for a like purpose’ as the male customers.

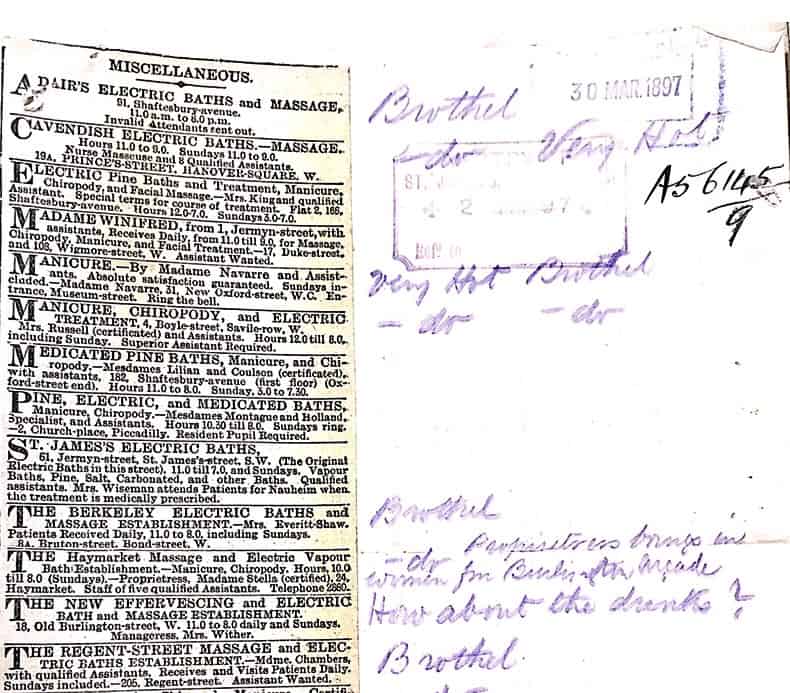

Considering the evidence of brothels posing as massage houses, both medical and government authorities pushed for a form of licensing to be enforced by local authorities. With such a measure massage houses would have to register their businesses and ensure treatments were provided to customers by members of the same sex. The negative attention and legislative actions focused on the massage parlour had provoked advertisers to change their advertising tactics. A police report from 1897 reported that advertisers had changed the name of their enterprise, now using the guise of manicure or chiropody instead. Police therefore started tracking advertisements for manicure and engaged in more observational tactics on certain listed manicure establishments. The advertisement column below illustrates these tactics. Many of the establishments were noted by police as brothels, but they advertised themselves as manicure, electric baths, vapour, effervescing, pine baths and chiropody treatments.

The continued publication of these advertisements under different therapeutic services provoked anger from anti-vice activists. Robert Corfe of the Public Morality Council wrote to the Home Office in 1901 complaining that he was still seeing them in papers. In 1908 he submitted evidence to the Joint Select Committee on Indecent Advertisements describing the changing textual tactics of those advertising sex:

First Massage; then everybody understood what that meant, and the name was never seen in public. Then the word manicure was substituted in these advertisements, and after a time that was understood and stopped, now it is ‘rheumatism’ or French lessons, or whatever it may be, but the same thing goes on; these are advertisements of certain houses which are known to the local councils and to the police.

By 1914 by-laws incorporated a wider range of named services to address the changing advertising tactics and regulate massage establishments, but soon more complaints appeared noting that advertisers had since changed their advertisements to ‘teachers of languages’.

Legislators were always chasing a moving target, and with each action against a particular therapeutic service, ‘illicit’ businesses simply changed the name and advertised nature of their business. The process of separating legitimate and illegitimate therapeutic services did, however, challenge the cover they provided the sex work industry, further pushing sex workers into ever more clandestine means of operating and advertising. The massage scandals also had longer linguistic legacies in the often fraught, but lingering, casual associations between massage and sex work. The authorities’ desire to decode, define, relegate and constrain sex work and its advertisement persists, but the massage scandals of the turn of the twentieth century illustrate that sex workers’ adaptability and ingenuity would always leave this desire unfulfilled.

SOURCES:

Ueyama, T. Health in the Marketplace: Professionalism, therapeutic desires, and medical commodification in Late-Victorian London. (Seattle WA: University of Washington Press, 2010).

National Archives: MEPO 2/460; HO 45/10912/A56145

Wellcome Collections: SA/CSP/P/1/2

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com