What common cause could bring organized labor together with gay liberation in the United States? When gay rights became a referendum question in municipal or statewide elections, unions’ strategic and direct participation or their indifference mattered profoundly for the fortunes of gay rights.

Beginning in 1972, dozens of cities and towns across the United States enacted or expanded civil rights codes with sexual orientation as a protected class. Five years later, religious conservatives introduced voters’ initiatives to repeal those reforms, and, at the state level, to enact new laws directed at the sexual morality of school and social service employees. The political attacks on gay rights were supposed to energize an emerging conservative electorate by representing its political leaders as the guardians of morality, the family and traditional sexual values. But the right’s mission and strategies yielded mixed results. Queer communities needed a strong defense and found, when they worked with organized labor, a means of countering an ascendant conservative movement.

In January 1977, Dade County Florida’s Metro Commission approved Ordinance 77-4, a civil rights ban on discrimination based on “affectional or sexual preference” for public accommodations, housing and employment. By that time similar protections had been enacted in dozens of cities and towns across the US, from Washington DC to Seattle, Washington and from Flint, Michigan to Aspen, Colorado. Most ordinances won passage without major controversy.

Gay civil rights in Dade County, which included the city of Miami, followed a different trajectory. Objections emerged early and then erupted into loud protests when it passed. Leading the charge was Anita Bryant, a former beauty queen and entertainer, now the official spokesperson for Florida citrus products. She served as the face of Save Our Children, a vigorous coalition that joined a core of conservative politicians – both Republicans and Democrats – to a broad swath of conservative clergy and their congregants: Catholics, Southern Baptists, Evangelicals, Conservative and Orthodox Jews.

Under Dade County law, if residents collected a petition with ten thousand signatures in less than thirty working days, the Metro Commission would have to reverse itself or call a special referendum. Financial and political support from powerful conservative networks drove a petition drive staffed by local volunteers. On February 22, SOC reported six times the required number of signatures. The commission stopped counting after confirming 13,450 names and approved the referendum for a special election to be held June 9, 1977.

In their public campaign, SOC supporters never mentioned the public policy aspects of the referendum: fair housing, fair hiring or the right to be served in a restaurant or shop in a store. SOC defined its parameters narrowly: the jobs of gay male teachers should not be legally protected. Bryant warned against these men and their predatory lusts; schoolboys would be their natural prey: “since homosexuals cannot reproduce, they must recruit.”

Hank Wilson, a San Francisco teacher and community activist, arrived in Miami to organize resistance to SOC, as did other volunteers from California, New York City and Washington D.C. They found a community poorly prepared and politically isolated. “We were being attacked and we didn’t have predictable allies,” Wilson said. He had worked on the Coors beer boycott, a vibrant, long-term campaign that joined gay liberation to labor’s concerns. The union was Teamster Local 921, which represented Bay Area beer truck drivers; the common cause was Coors’ anti-gay, anti-labor employment practices; and the boycott was still alive in the taverns of San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood and spreading successfully to ever-larger markets throughout the west.

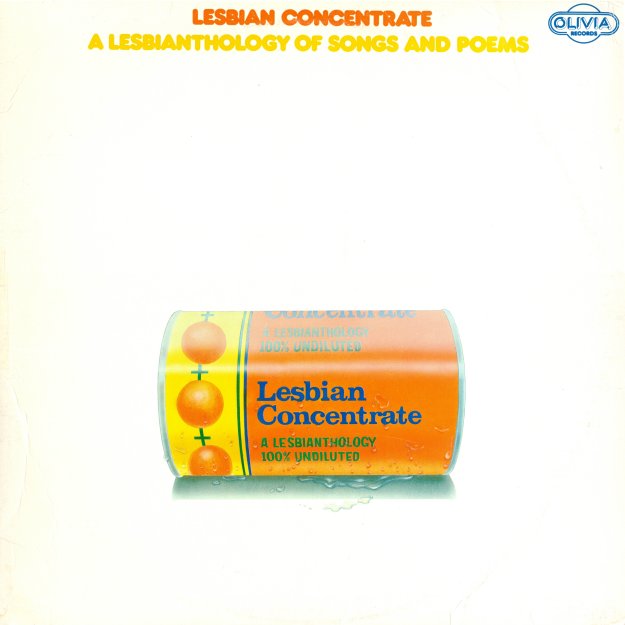

Gay activists turned the boycott tactic against Anita Bryant and her leadership of SOC. They targeted Florida’s citrus products and the idea caught on. Olivia Records, an all-women music production company, recorded “Lesbian Concentrate,” a musical anthology to benefit the cause, with Linda Tillery calling out Bryant on the album’s first cut, a funk number. “Don’t pray for me,” she sang, “Sweet Christian lady preachin’ hate.” Orange juice profits dropped enough for Bryant to feel the pressure; but she would not back down.

Unlike California, unions in Florida wielded little influence on public policy. Florida was a “right-to-work” state. Federal law allowed its unions to organize workers and negotiate contracts, but state law permitted workers covered by those contracts to refuse union membership and the payment of dues. Neither the Florida AFL-CIO nor local unions involved in Miami’s robust tourist economy took a stand. The campaign’s sole union ally was Local 1974 of the American Federation of Teachers, the United Teachers of Dade, which represented 18,000 Miami school workers. “We were concerned that SOC could result in a witch hunt against gay teachers and against gay students,” said Annette Katz, a Local 1974 staffer.

With almost 70 percent voting “yes,” the repeal carried. But children–especially gay youth–were not being saved. “I was following the national statistics on teen suicide, and in February 1977, when SOC was launched, the numbers jumped off the scale,” Hank Wilson recalled. “People don’t know why, but I think I do. When the topic surfaced it affected young gay people. All of a sudden, their parents, the people they counted on for support and love, weren’t there. Their parents were agreeing with the hate.”

In spring 1978, Bryant took her victory on tour to support three new campaigns against standing gay rights ordinances in St. Paul, Minnesota; Wichita, Kansas; and Eugene, Oregon. Eugene’s lesbian community attempted to organize a resistance, but most LGBT people in these cities were not out at their jobs and their churches or with their families. Because their invisibility helped hide the discrimination that they suffered, they could not effectively answer conservative claims that gays did not actually need legal protection. Gay liberation had no standing with their communities’ unions, even where right-to-work sanctions did not prevail (St. Paul and Eugene). Anti-gay drives easily triumphed.

After a year of defeats the trend reversed – twice – during the fall of 1978. A rising sector of Seattle’s labor movement took a stand for gay rights after two police officers initiated “Save Our Moral Ethics,” a drive to overturn the city’s standing gay rights ordinance. Gay and lesbian groups joined in coalition with civil rights and liberal religious organizations to defend the ordinance. Late in the campaign Proposition 13 lost credibility when one of the police officers shot and killed a burglary suspect, a young, mentally disabled black man. Lesbian and gay activists joined in with black community groups to protest the shooting and their alliance stood firm as election day approached.

The King County Labor Council considered support of Proposition 13, but not all unions agreed. Seattle’s unions in the public and service sector backed retention of the ordinance, while construction unions favored repeal. Madelyn Elder, a craft splicer at the telephone company and a “No on 13” activist, attended Council meetings to urge support. But after witnessing her opponents’ vehemence she was satisfied when the Council endorsed neither side. Seattle voters retained the ordinance by 63 percent. This was the nation’s first municipal repeal referendum on gay civil rights to be defeated.

During that same electoral season in California, voters considered Proposition 6, a referendum sponsored by Senator John Briggs that threatened dismissal of queer school workers who declared their own sexual identities, and any school worker, gay or straight, who advocated tolerance of LGBT existence. Political clubs and queer communities, civil liberty advocates, and liberal religious groups mobilized to oppose Proposition 6. They alerted their own constituencies and a wider public. Some activists traveled to rural communities to meet with church congregations; others canvassed in their own neighborhoods.

Teachers’ unions led the anti-Briggs resistance in the labor movement. Union leaders, aware of Senator Briggs’ consistent hostility to collective bargaining, did not remain neutral. They warned members that Proposition 6 would violate collective bargaining contracts and invited queer community activists to speak at their local union halls and regional labor councils.

Labor’s influence had already eroded support for Proposition 6; and then towards summer’s end, the right split. Fiscal conservatives worried that the proposition’s complex investigative mandate would generate major bureaucratic costs. Several Chambers of Commerce endorsed this position and, in the last weeks, so did former Governor Ronald Reagan, an arch-rival of Senator Briggs. Proposition 6 was losing momentum even before California labor unleashed its mighty political machine to get out the vote. This was labor’s organizing power at its most effective: front-page endorsements in the AFL-CIO newsletter, union volunteers staffing phone banks statewide for several days ahead of the vote and even more volunteers handing out 2.3 million cards at the polls. Proposition 6 lost by 58 percent.

Those two failures of anti-gay voters’ initiatives put an end to ballot box bigotry for the next fourteen years and sealed a coalition of partners in Seattle and California: labor unions and LGBT organizations supported by civil rights and liberal religious groups. Then, in 1992, conservatives in Colorado and Oregon once again attempted to codify anti-gay discrimination via statewide ballot initiatives. The intervention of organized labor once again made all the difference.

Long-standing right-to-work sanctions in Colorado shackled its unions. They rarely got involved in political contests that didn’t affect immediate economic goals. Colorado’s liberal alliance of religious groups, LGBT communities, and civil libertarians was a much weaker entity, therefore, and lacked the get-out-the-vote skills that made labor such a potent partner in political coalitions. Criticism of Amendment 2 to the state constitution was not part of the union dialogue in the 1992 election. When Colorado voters approved the amendment they suddenly had a law that would nullify all statewide executive orders and all municipal civil rights ordinances that had protected LGBT citizens from discrimination.

The American Civil Liberties Union led a battery of legal challenges (Romer v Evans). For the next three years state and federal appeals courts ruled against it consistently until the Supreme Court struck it down in 1996; the Amendment itself was never enforced.

Oregon’s labor movement was free from right-to-work restrictions. During the early 1990s its unions were pressured by a tough economy; but the labor, LGBT, liberal religious and civil liberties coalition consistently defended queer union members from major attacks by Oregon’s ultra-conservative Oregon Citizens Alliance. The OCA advanced several different discriminatory ballot measures in statewide referendums in 1992, 1993 and 1995, each intended to eliminate civil rights of sexual minorities from Oregon’s Bill of Rights. Service Employees Local 503 led labor, liberal religious and civil rights groups in a resistance vigorous and diverse enough to persuade voters to reject the hostile ballot measures every time.

Oregon’s forthright resistance inspired another clear outcome in labor-LGBT politics. In 1994 SEIU’s Local 1199 Northwest received a call for support from Hands Off Washington, a coalition that sought to defeat a petition drive for Initiatives 608 and 610, two anti-gay proposals, both being prepared for the state’s next general election. Marcy Johnsen, a nurse and a union officer in 1199 Northwest, came out as a lesbian at a union assembly, which discussed whether 1199 should support Hands Off Washington. This act of disclosure was a breakthrough that shocked some members, but was worth it to Johnsen. The union voted support for Hands Off Washington and Johnsen continued to serve 1199 Northwest as an openly lesbian officer. The union’s decision helped to squelch petitioning, and proposals 608 and 610 never made it to the ballot.

Gay communities and unions changed during the seventeen years between Save Our Children’s devastating defeat of gay civil rights in Miami and Hands Off Washington’s pre-emptive victory. The two movements had learned to rely on one another, They saw that tight mutual support could forestall legalized bigotry on the job and in the community. Shared projects and common causes deepened that trust. Practical coalitions like No on 13 in Seattle prompted the AFL-CIO and national unions to include sexual orientation in their constitutional civil rights articles. The domestic partner benefits plan negotiated by one white-collar unit of District 65-UAW became a model throughout the US workforce. And San Francisco AIDS activists collaborated with hospital unionists to produce “AIDS and the Health Care Worker,” a booklet that was distributed nationally through five editions, including one in Spanish.

These two movements, so different in goals, organizing styles, and constituencies, intertwined productively because, at their best, they affirmed solidarity and mutual defense. “We Are Everywhere,” the coming-out slogan of gay liberation, surely applied to the workers of the world even as labor’s classic motto, “An Injury to One is an Injury to All,” has rightly extended its reach to queer folk in the ranks.

Miriam Frank received her Ph.D in German Literature from New York University in 1977, where she currently is Adjunct Associate Professor of Humanities. She has taught Labor History in union education programs in New York City and in Detroit, where she was a founder of Women’s Studies at Wayne County Community College. Her book, Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America (Temple University Press, 2014), chronicles the queer lives of American workers from the mid-1960s through 2013. This history is based on 100 interviews with LGBT labor activists who came out on their jobs and in their unions to organize for civil rights and gay dignity.

Miriam Frank received her Ph.D in German Literature from New York University in 1977, where she currently is Adjunct Associate Professor of Humanities. She has taught Labor History in union education programs in New York City and in Detroit, where she was a founder of Women’s Studies at Wayne County Community College. Her book, Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America (Temple University Press, 2014), chronicles the queer lives of American workers from the mid-1960s through 2013. This history is based on 100 interviews with LGBT labor activists who came out on their jobs and in their unions to organize for civil rights and gay dignity.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thank you for engaging with the important issue of collaboration between the gay liberation movement and what I would call the trade union movement. I am well aware that there are great differences between the histories and the modes of organisations of trade unions in the UK and the USA. But one of the things that I was curious about after reading your posting was the way in which these anti-discrimination issues were raised within the unions themselves. In the UK self-organisation of gay people (using 1970s parlance) within the unions was an essential part of the process of engaging with such issues. From around 1974, a number of gay groups were set up within trade unions by members who had also been part of the gay liberation movement. Alliances were then formed with left-leaning rank and file groups within those same unions. In the early stages, these activities were around issues of general principles of discrimination; by the time major crises arose around, for example, Section 28 and its attempts to outlaw ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in publicly funded schools, the debate within the unions was sufficiently mature for the unions to be full and active participants in the movement to resist such laws. The British Library Sound Archive holds oral history interviews with lesbian and gay trade unionists who were involved in this process of self-organisation as well as subsequent related campaigns; these interviews were conducted by the Millthorpe Project. http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelprestype/sound/ohist/ohcoll/ohsex/sexuality.html

And thank you, Bob Cant, for your curiosity about the ways that LGBT politics emerged and became forceful within the US labor movement. My essay’s focus on labor/gay defenses against right-wing campaigns is one important piece of what I wrote about in OUT IN THE UNION. The movement for LGBT rights advanced by queer unionists and allies during the late twentieth century was ambitious and diverse and it continues today. Issues have ranged broadly. Queer teachers in the huge teachers’ unions of New York City and San Francisco were the first to self-organize lesbian/gay groups in the early 1970s, but first had to push hard on their “parent” unions to recognize their programs as necessary union business. That changed on both coasts with the right-wing threats of the Briggs Amendment in California and the battle in Seattle over Proposition 13, both in 1978.

By the mid-1980s, activists in the service and public sectors were forming ad hoc local union caucuses to advocate for domestic partner benefits; and with the advent of the AIDS crisis, hospital workers – gay and straight –set up union-based AIDS education projects to alert colleagues on the fundamentals of safe workplace practices. In the private sector, queer union caucuses, especially in local unions, influenced bargaining and organizing agendas. As in the UK, activists were often veterans of gay liberation; and left-leaning rank-and-file groups within local unions were especially reliable advocates.

During the 1990s, SEIU and AFSCME (the service and public employee unions) fostered union-wide conferences and advocacy programs for LGBT rights. These formations were effective at thwarting right-wing campaigns in Oregon and Washington State, as told in my essay; and they played supportive roles in other political causes of their unions.

My book, OUT IN THE UNION, takes on the queer labor history of this hugely diverse nation and will surely raise new issues, even as it fills in some of the questions that this first response suggests.

This is fascinating stuff and I echo Bob in thanking you for your work – I will get a copy of your book asap – it looks like it would serve as an inspirational model for what could be done here if only there was a will to do it. Some time ago Bob posted here asking who will take responsibility for capturing our history and the example he used was of the left-wing local council of Haringey. From the complete lack of response here (other than from me) it seems clear that those of us paid to work in the field don’t want to or cannot take on the responsibility (I myself do my “gay history” in odd moments as I can only rarely justify it in terms of my job as a lecturer in law).

Just to point out that in Britain, as Bob says, the preferred term would be trade unionists – here “unionists” are reactionary British nationalists (most commonly associated with the protestant cause in the north of Ireland but also the Conservative, Labour and LibDem parties).

Brian – thank you for your regular comments on Notches. And, thank you and Bob Cant for inviting others to research the intersections of queer and labor history in the UK. I suspect that it might take some time to respond to Bob’s call for more research on these important issues. And I join you in encouraging scholars to do so. I also hope that steps are being taken to record and preserve the voices and records of lgbt workers and trade unionists in the UK.

One of the wonderful aspects of Miriam Frank’s book is her use of oral histories (I hope that she will donate her to an archive for future researchers to use). Are there are any efforts in the UK to record the oral histories of glbt workers / trade unionists?

To be honest I am not sure what work is being done by UK academics on this. There are many opportunities, some of which are slipping away. I attended as an observer an LGBTI event organised by a political party recently as it had a session on “gay history” – it was a pretty pointless exercise but one person from the floor told how he had been closeted within the party for a long time and was reflecting on the dynamics (not pure homophobia, but that was an element) and called on some of the c.200 people in the room to find a way to capture their collective history – unfortunately neither the chair nor the speakers took up the challenge even to the length of getting interested people to contact them. I am happy to collaborate with any initiative, UK, Scots or wider, to capture trade union and progressive party lgbti history but I do feel that those with the expertise should take the lead – if not then I’ll see what I can do in a couple of years time when present projects are, hopefully, completed.

I think discussion around the connections between causes dear to the hearts of the LGBT communities and to trade unions is highly important. The recent film, Pride, highlighted the value of solidarity between striking mineworkers and LGBT communities. The patterns of organisation by LGBT workers within trade unions is probably less open to cinematic exploration than the events explored in Pride but no less worthy of our attention. I agree with Gillian’s point about the value of oral histories and I have just been reading some of the sadly unfinished work by Allan Berube about activities within the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union (MCSU) between the 1930s and the 1950s. His oral history interviews with surviving trade unionists enabled us to gain access to the voices of people who would otherwise have been overlooked and forgotten. As you can see from my earlier message in this thread, the Millthorpe Project carried out a number of interviews with LGBT trade unionists which are held at the British Library. It was a small project and we were only able to record the stories of ten people; we also had a limited budget which came from my union, University and College Union (UCU) and the Trades Union Congress (TUC). But the interviews are there and able to provide the base for community activists and scholars to build upon.