Homosexuals cannot reproduce—so they must recruit, and to freshen their ranks, they must recruit the youth of America.

– Anita Bryant

In 1977, Anita Bryant became the face of a right wing religious coalition, Save Our Children (SOC). SOC, which was based in Dade County Florida, enshrined into national conservative politics the idea that homosexuals should not be given equal rights because they are a threat to children. Historians frequently use Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign as shorthand for the growing importance of conservative Evangelical voters, the rise of the Religious Right and the concurrent ascent of anti-gay politics. Little attention has been given to how the struggle over gay rights evolved within the context of Dade County’s large and politically active Jewish community.

Analyzing Jewish responses to a gay civil rights law in 1977 enriches historians’ understanding of Jews’ varied relationship with both conservatism and liberalism. In 1977, Jews comprised approximately 15% of Dade County’s population and were an important voting bloc. Both pro- and anti-gay activists sought to appeal to Jewish voters, and did so respectively by invoking the legacy of the Holocaust or longstanding Jewish fears of demographic decline. These appeals created divides within and between denominations. Although a significant number of Jewish voters opposed gay rights in 1977 and bolstered a nascent conservative religious coalition, many more expanded their definition of liberalism to include sexual politics.

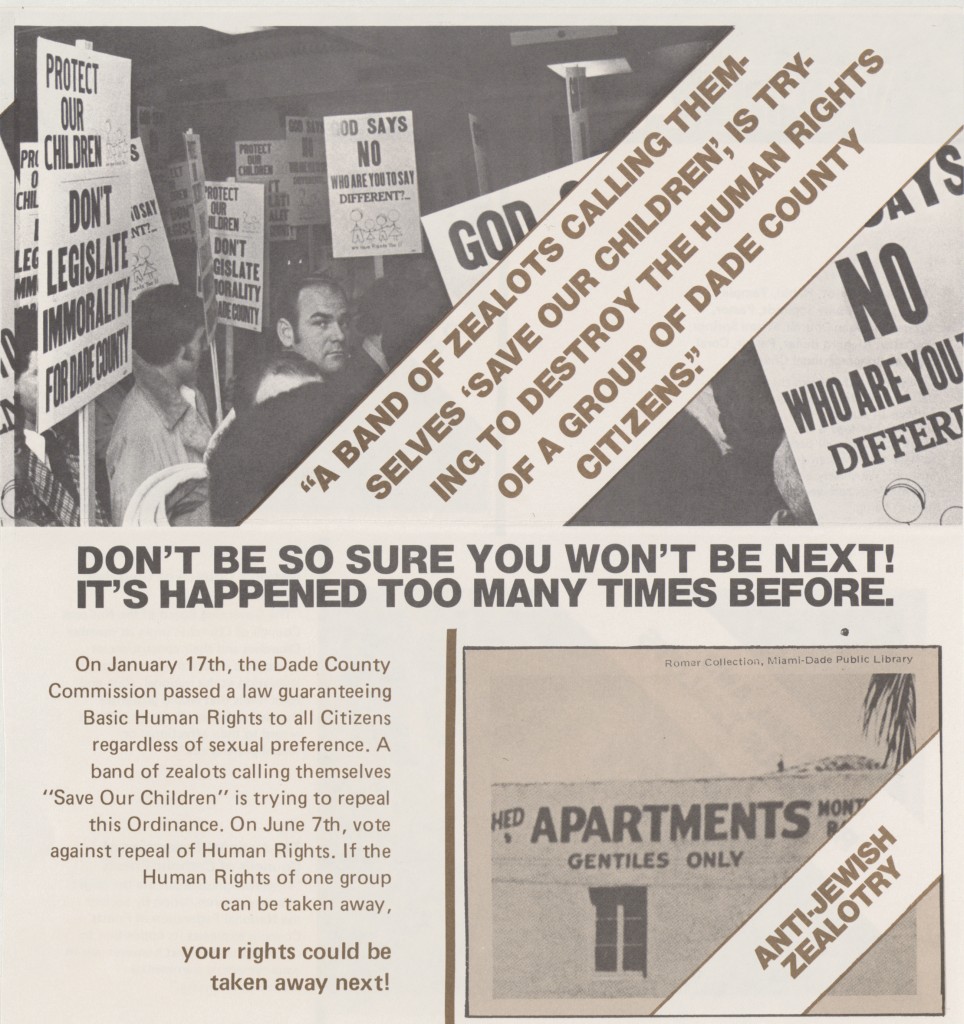

SOC opposed a gay rights ordinance in Dade County, Florida that prohibited discrimination based on “sexual or affectional preference” in the areas of housing, public accommodations and employment. With Bryant as its spokesperson, SOC initiated a referendum campaign to repeal the law. As the June 1977 referendum neared, the pro-gay group Dade County Coalition for Human Rights (DCCHR) attempted to rally traditionally liberal voters to its cause. It regarded Jews as potential allies because of Jewish organizations’ longstanding commitment to racial and religious tolerance, pluralism and egalitarianism. DCCHR created targeted advertisements for Jews that compared homophobia to anti-Semitism and highlighted a shared history of discrimination. A fundraising letter entitled “The Yellow Star and the Pink Triangle,” explained that in Nazi Germany, homosexuals “had to wear pink triangles in public, just as Jews had to wear a Star of David” and underscored that the Nazis murdered both groups. DCCHR also used American Jewish strategies for combating anti-Semitism by describing bigotry as a pervasive condition that threatened all minorities.

These arguments had purchase among some segments of the Jewish vote. A liberalization of attitudes toward homosexuality was taking place gradually in Conservative and Reform denominations. In Dade County, Reform rabbis were among the most ardent supporters of gay rights. Such was the case when Reform Rabbi Kingsley gave a well-publicized sermon entitled “The Gay Lifestyle and Society – Whose Problem Is It, or Why Is Anita Bryant So Up Tight?”

However, these supporters were the exception, not the rule. In 1977, most rabbis, especially from Conservative and Orthodox denominations, maintained that opposition to homosexuality was the authentic expression of Jewish values. In this vein, SOC courted Jewish voters and worked with Orthodox rabbis and a prominent Conservative community leader to emphasize the “religiousness” of Jewish opposition to homosexuality. SOC’s ecumenical campaign literature, moreover, carefully emphasized how both “Judaism and Christianity are strongly against homosexual acts.” Anita Bryant structured her own rhetoric to engage Jewish community members by noting that, “putting gays as teachers in the public schools is like shoving ham down the face of [a rabbi].” Orthodox Rabbi Phineas Weberman, a member of SOC, likewise stated that Jewish law, “prohibits parents from allowing their children to be taught by people who are sexually perverted.”

Overlapping with these theological enjoinders against homosexuality were the lived religious values shared by Jews and Christians that emphasized heterosexual marriage and reproduction. SOC appealed to the powerful belief that all children ought to be heterosexual and that society had a stake in preventing the development of homosexuality in children. Historian Michael Staub explains that Jewish leaders from all denominations subscribed to the powerful argument “that a properly respectful response to the fact of the Holocaust was to strengthen Jewish family life and make more Jewish babies.” Jewish commentators framed homosexuality as antithetical to children and the family. As one author in the San Francisco Jewish Bulletin noted in 1972, homosexuality “is by its nature antithetical to the idea of children, to the idea of continuity, and finally to the concern about future generations.” Pro- and anti-gay appeals thus navigated two competing traditions: a legacy of challenging discrimination and a practice of cultivating Jewish pronatalism. The aim of the Save Our Children campaign was to lead a significant portion of Jewish voters to believe that these two choices were mutually exclusive. To do so, they mobilized a pro-family and pro-fertility Holocaust consciousness and disavowed the overlapping histories of the yellow star and the pink triangle.

SOC successfully repealed the measure and in so doing created the template for decades of opposition to gay rights across the United States. It would be easy to conclude that the defeat of gay rights in Dade County by a 2-1 ratio marked the triumph of an interdenominational conservative sexual politics. The numbers, however, suggest a more complex story. Catholic and Protestant voters, especially those in working-class and Cuban neighborhoods, turned out in droves to oppose gay rights whereas Jews had an uncharacteristically low turnout. The majority of voters in precincts with high Jewish populations, moreover, supported the gay rights ordinance, albeit by narrow margins. Put differently, while Orthodox Jews joined with religious conservatives to oppose gay rights, most Jewish voters were unmotivated by anti-gay appeals. Reports at the time suggest that of those Jews who voted, more endorsed gay rights than did not.

The 1977 referendum should be understood as a moment of debate within and among Jewish (as well as Christian) denominations. In the 1970s, at the polls and in their synagogues, Conservative and Reform Jews began expanding their definition of liberalism to include sexual minorities. Conversely, Orthodox Jews nationwide opposed homosexuality in the pulpit and used SOC-inspired rhetoric in political campaigns against gay rights. The Dade County campaign thus brought religious debates and denominational divides over homosexuality into the national political arena with profound consequences for religious and political identities that continue to reverberate to this day.

Gillian Frank is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. Gillian’s research focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race, childhood and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently revising a book manuscript titled Save Our Children: Sexual Politics and Cultural Conservatism in the United States, 1965-1990. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Excellent piece. Really interesting. Good luck with your book.

Kudos to Gillian Frank. Neglected for far too long, the Jewish collaboration with the infamous 1970s political and religious crusades was a subject roundly silenced. My own inquiries in the 1980s led to accusations of anti-semiticism and worse, and my suggestions to other scholars for such research were contemptuously dismissed. I look for more documentation on this period, especially since many of its participants, aggressors and victims, are still alive.

Pingback: Organized Labor, Gay Liberation and the Battle Against the Religious Right, 1977-1994 | NOTCHES