From Ireland’s recent referendum in support of same-sex marriage to the Australian Prime Minister’s adamant refusal to offer a conscience vote on the same issue, countries around the world are once again talking about homosexuality. But for all the positive steps taken towards granting LGBTI citizens the same rights as non-LGBTI citizens, one part of Northern Italy in particular has in fact taken a major leap backwards. A journalist, Matteo Pucciarelli, writing in one of Italy’s main newspapers, La Repubblica, recently revealed a new movement to ‘pray the gay away’ at a Catholic retreat in Angolo Terme in Brescia.

A former homosexual and gay activist, Luca di Tolve, has teamed up with two religious leaders and is charging €185 for a five-day seminar that will ‘cure’ attendees of their disease – homosexuality. In his seminars, di Tolve emphasizes that, ‘Homosexuality does not exist, and you are not gay. You are just people with a problem’. Offering a combination of prayer and sessions with titles such as ‘Regaining your masculinity’ and ‘Rediscovering your femininity’, di Tolve describes homosexuality as both a sin and a medical problem. For those interested in Italian history of sexuality, and in the history of homosexuality in particular, there are at least two important aspects worth highlighting about this Italian ‘pray the gay away’ retreat and the recent comments by the Catholic Church on homosexuality.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, some medical doctors such as the Austro-German Richard von Krafft-Ebing started to argue that homosexuality, or ‘sexual inversion’ to use sexologists’ language, was an inborn condition and a pathological condition of the nervous system. Others, such as the Englishman Havelock Ellis, agreed that homosexuality was an inborn condition but rejected the notion that it was a disease. Sexologists’ idea that homosexuality was an inborn condition was crucial for gay rights struggles, which used this concept to counter legal and religious arguments that assumed that homosexuality was a choice and a sin. If homosexuality was inborn it could not be punished by law since it would have been unjust to punish a man for being born a certain way. Famously, in England Havelock Ellis and John Addington Symonds adopted medical arguments to challenge the criminalisation of male homosexual acts under the 1885 Labouchère Amendment.

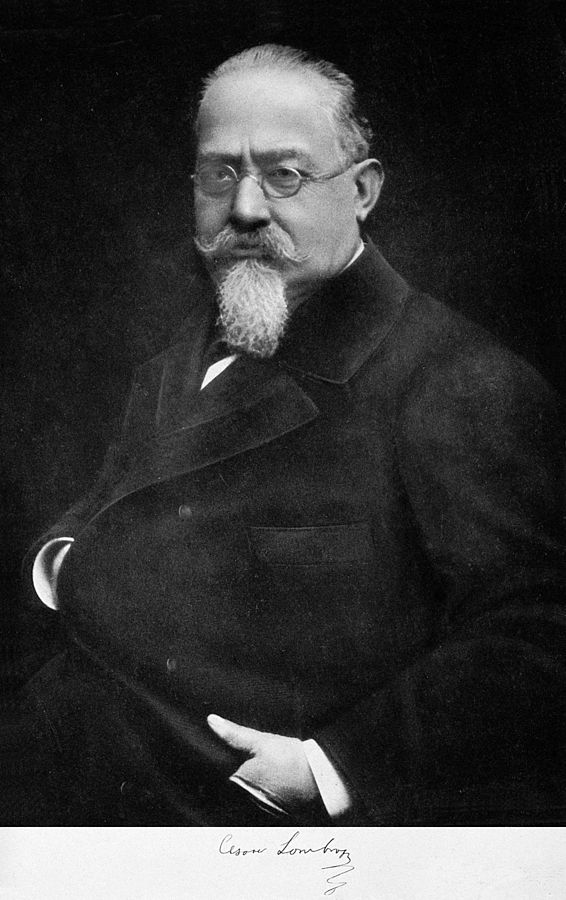

In late nineteenth-century Italy, medical men employed these new sexological ideas to challenge the authority of the Catholic Church in sexual matters. While homosexuality for some doctors, such as the well-known Cesare Lombroso, was a disease, for other more progressive medical experts like Pasquale Penta, homosexuality was simply an inborn condition but not a disease. Regardless of these two different medical perspectives, late nineteenth-century Italian sexologists were united in arguing against the Catholic Church and its position that homosexuality was a sin. Crucially, this was also part of a larger battle in post-unification Italy that saw a bitter conflict between the new Italian government and the Vatican, which refused to recognise the new Italian Kingdom. As I argue in my book, in Italy the emergence of sexology itself can only be fully understood when considered alongside the staunch anticlericalism of late nineteenth-century Italian sexologists.

Catholic authorities, however, have recently adopted the old-fashioned association between homosexuality and pathology, even though medical authorities decategorised homosexuality as a disease in the US and other Western countries in the 1970s. In April 2010, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, perhaps the most important person in the Vatican hierarchy after the Pope, linked homosexuality to paedophilia, using psychiatry to support his case. He observed that “…many psychologists and psychiatrists have demonstrated [. . .] that there is a relation between homosexuality and paedophilia. It’s a pathology that relates to all social categories…” Here Bertone was employing outmoded medical theories that argued that homosexuality was a disease to support his religious views on homosexuality. Psychologists and psychiatrists promptly disavowed Bernone’s statements, but this hasn’t stopped the Catholic Church from re-appropriating and adapting nineteenth-century medical ideas.

Tolve’s five-day Catholic retreat and seminars show that clerics in Italy are still trying to gain ground in their crusade against homosexuality by using the tools of the sexologists who once opposed them. In other words, the Church is now endorsing the very nineteenth-century medical views that were developed in Italy by sexologists who were fundamentally anticlerical.

This ironic appropriation dovetails with a second irony: Italy was once admired and respected for its liberal attitude towards homosexuality. Throughout the nineteenth century, Southern Italy did not legally punish male same-sex sexual acts. Indeed, from the introduction of the Zanardelli code in 1889, which decriminalised male same-sex acts on a national scale, homosexuals such as John Addington Symonds and other persecuted men like Oscar Wilde viewed Italy as a refuge against social and legal intolerance at home. Many wealthy British and German men quit their own country and went to live in Italy in this period.

The distance between the end of the nineteenth century, when Italy was at the forefront of anticlerical ideas about sex, and the twenty-first century, is significant. Today in Italy there are no basic rights for homosexuals; there are no specific laws against homophobia or discrimination because of sexual orientation; and Italy is now the only country in Western Europe that does not recognise same-sex partnerships. Continuing its battle against homosexuality, the Vatican’s current Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, dubbed the recent Irish vote in support of gay marriage ‘a defeat for humanity.’

For all its progressive politics in the late nineteenth century, it is clear that old arguments are now being repurposed to attack those that they once protected. While Italy may be a shining light when it comes to many things – history, art, culture and even its humane response to the plight of refugees – it stands out as a bastion of intolerance for one group that still faces discrimination in many parts of the world. To be LGBTI in Italy might not be illegal, but there are no laws protecting its citizens from homophobic attacks or from facing discrimination because of who they happen to love.

When it comes to LGBTI rights, Italy still has a long way to go, and perhaps the way forward may involve looking back on Italian history and rediscovering some of the liberal attitudes towards homosexuality for which the country was once so famous. To do so, Italian politicians would also need to rediscover some of the healthy anticlericalism that characterized the post-unification period. If they can find a way to do this, we might finally see the passage of long awaited laws against homophobia, and the granting of LGBTI citizens the same rights as their non-LGBTI neighbours and friends. Or have Italian politicians forgotten the long struggle to ensure that Italy be a secular state?

Chiara Beccalossi is a Lecturer in the History of Medicine at Oxford Brookes University. Her research interests range across the history of sexuality, the history of medicine and the history of human sciences in Europe, in particular Italy. Chiara’s first book was Female Sexual Inversion: Same-Sex Desires in Italian and British Sexology, c. 1870–1920 (2012), which explored how medical men in Italy and Britain pathologised same-sex desires. She has also co-edited Italian Sexualities Uncovered, 1789-1914 (2015) with Valeria P. Babini and Lucy Riall, A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Age of Empire (2011) with Ivan Crozier, and has published numerous articles in the field of history of sexuality and medicine. She tweets from @ChiaraBcc

is a Lecturer in the History of Medicine at Oxford Brookes University. Her research interests range across the history of sexuality, the history of medicine and the history of human sciences in Europe, in particular Italy. Chiara’s first book was Female Sexual Inversion: Same-Sex Desires in Italian and British Sexology, c. 1870–1920 (2012), which explored how medical men in Italy and Britain pathologised same-sex desires. She has also co-edited Italian Sexualities Uncovered, 1789-1914 (2015) with Valeria P. Babini and Lucy Riall, A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Age of Empire (2011) with Ivan Crozier, and has published numerous articles in the field of history of sexuality and medicine. She tweets from @ChiaraBcc

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com