Gay politics today tend to be premised on the ‘born this way’ argument, the idea that being gay is not a matter of choice or preference, but rather an innate, natural and biologically conditioned fact of life. If homosexuality is something we are born with and therefore not something we choose or can be expected to change, the argument goes, we have the right to demand protection under the law, equal rights and social acceptance more generally.

While incredibly pervasive (think Lady Gaga, Macklemore or Glee) and undeniably powerful, the ‘born this way’ argument has also been subjected to substantial criticism. Even though stories about the ‘gay gene’, for example, continue to circulate in popular media coverage, most scientists are very hesitant to assert that there is any straightforward link between potential genetic variation and sexual attraction. Scholars in the humanities and social sciences, especially history and anthropology, have also challenged the ‘born this way’ argument. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that different cultures in the past and present did not distinguish clearly between ‘homosexuals’ and ‘heterosexuals’. Instead, such cultures often developed entirely different ways of understanding sexual desire that resist the idea that there is a social minority group consisting of individuals who are simply ‘born gay’.

Less frequently discussed in the context of these political debates are the historical origins of the ‘born this way’ argument itself, which we can trace back at least 150 years or so. Following Foucault, it is commonly agued that sexual science or sexology emerged in the nineteenth century and invented the notion of the homosexual as a separate kind or ‘type’ of being whose physical and psychological make-up was different from that of others. Needless to say, early sexologists tended to view such difference as pathological and as indicative of deviance and degeneration – homosexuals, according to this view, might be ‘born this way’, but it was not seen as a cause of celebration or affirmation at this earlier historical moment.

While we might think that we have come a long way with the likes of Gaga instructing her audience to “rejoice and love yourself today / ’cause baby, you were born this way”, it is worth questioning to what extent such earlier pathologising views of homosexuality persist and, indeed, go unnoticed when we rehearse the ‘born this way’ argument today. Why, for instance, would it not be ok to be gay if homosexual desire were not simply biologically determined? Do we unintentionally perpetuate the notion that homosexuality is somehow less desirable if we argue for social acceptance and equal rights on the grounds that we simply cannot help the way we feel, because we are somehow different by nature? Thinking about the historical origins of the ‘born this way argument’ and tracing the often problematic legacies of early sexological understandings of homosexuality can be informative and helpful in allowing us to confront blind spots in our own political rhetoric.

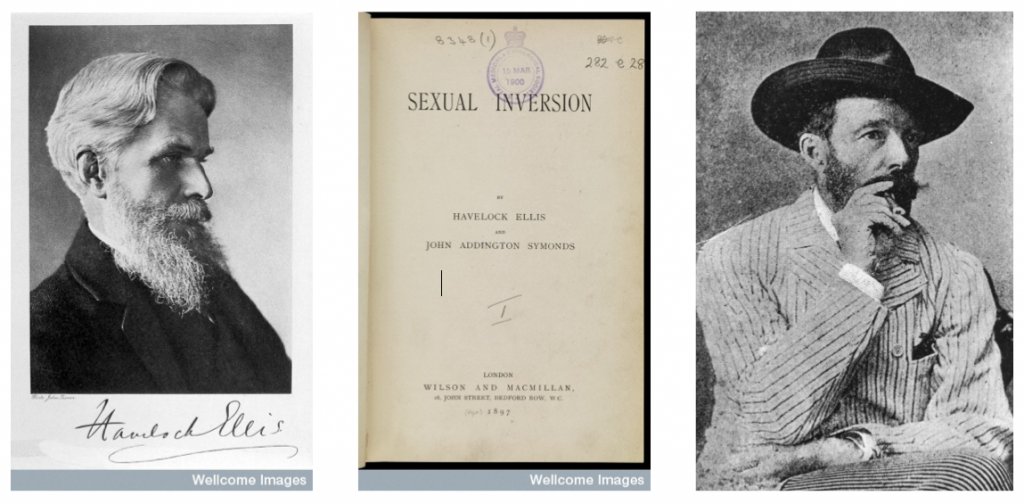

Crucially, the potential benefits as well as the problems of using the ‘born this way’ argument were not lost on nineteenth century sexual scientists themselves. The collaboration between Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) and John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) in the 1880s and 1890s, in particular, offers important insights into the historical invention of a powerful political strategy, which is still at the heart of gay politics and culture today. Ellis is remembered as the most eminent English sexologist and he collaborated with Symonds, a well-known Renaissance scholar, classicist and poet, to co-author the first medical textbook on homosexuality in England, a book called Sexual Inversion (first published and promptly banned as obscene in England in 1897).

If you read Sexual Inversion or study the correspondence between Ellis and Symonds, which has recently been published for the first time, it is very clear that both collaborators were keen to write scientifically about homosexuality or ‘sexual inversion’ to use their own terminology, but they also wanted to present a forceful political argument. In particular, they were eager to challenge the criminalisation of male homosexuality in England under the 1885 Labouchère Amendment and change social attitudes more generally. To achieve this shared goal, Ellis and Symonds reappropriated the views of earlier sexologists who had presented homosexuality as pathological. Instead, Ellis and Symonds argued that homosexuality was often inborn or congenital, but this did not mean that homosexuals were necessarily unhealthy or degenerate. They offered a range of evidence to show that homosexuals could be healthy, respectable and even highly accomplished members of society who did not deserve to be prosecuted. In other words, Symonds and Ellis presented homosexuality as an inborn and therefore natural sexual variation and, in so doing, were among the first writers to introduce the historical predecessor of today’s ‘born this way’ argument.

Ellis and Symonds’ correspondence suggests, however, that they also struggled considerably to make this argument work and that they were all too aware of its flaws. This is particularly evident in their discussion of past cultures and the possible uses of historical evidence, in particular, relating to Ancient Greece, which I have discussed at length elsewhere. Ancient Greece was useful in that it could demonstrate forcefully that civilisations that were remembered and celebrated for their moral valour and intellectual brilliance had accepted and even encouraged same-sex desire (between males). But Symonds and Ellis also knew and discussed openly that there was no easy way to apply a modern understanding of homosexuality as inborn or congenital to the Greek past, which was, after all, a remarkably different culture. When thinking about Ancient Greece, it did not make sense to argue that all men who experienced same-sex desire were simply ‘born this way’, since they grew up in a cultural environment that accepted and even encouraged such desires and did not differentiate between ‘homosexuals’ and ‘heterosexuals’. In other words, Ellis and Symonds were already very familiar with the fact that any ‘born this way’ logic collapses once we look at other historical periods or cultures.

Although Sexual Inversion does anticipate today’s ‘born this way’ argument in interesting ways, it is also crucial to recognise that Ellis and Symonds were both very aware of how flawed this argument was. While the idea that homosexuality was necessarily inborn or congenital was a useful strategy to work towards political goals, it also had considerable limitations and certainly did not capture all individual experiences never mind different cultural and historical understandings of sexuality. Reconsidering the ways in which modern scientific understandings of homosexuality emerged in dialogue with political and reformist agendas at this early moment in the history of sexual science is useful in reminding us of these fundamental problems. Ideally, this will allow us to take a step back and think critically about the more difficult and problematic legacies and flaws of the ‘born this way’ argument and perhaps enable us to work towards alternative, richer and more multi-layered understandings of sexuality.

Jana Funke is an Advanced Research Fellow in Medical Humanities at the Department of English and the Centre for Medical History at the University of Exeter. She researches and has published on late nineteenth- and early twentieth- century literature and culture, the history of sexuality, sexual science and the medicalisation of sex. She tweets from @drjanafunke.

Jana Funke is an Advanced Research Fellow in Medical Humanities at the Department of English and the Centre for Medical History at the University of Exeter. She researches and has published on late nineteenth- and early twentieth- century literature and culture, the history of sexuality, sexual science and the medicalisation of sex. She tweets from @drjanafunke.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Congratulations on being Freshly Pressed.

Thank you so much! I am thrilled.

This is very interesting. I had no idea that these studies even existed that long ago. I wonder how they justified making homosexuality illegal? Same thoughts apply today, how can one group decide for the whole that who a person falls in love with is illegal – unless of course it is harmful in some way to the collective… how do they respond to these questions, I wonder…

Being ‘born this way’ whichever that way is seems to imply an inability to control one’s own behavior. I don’t identify myself as heterosexual any more than I identify as white. Both are true, but I don’t parade around celebrating white pride. Besides, I think that is considered hate speech nowadays.

I think that a biological link is one of the least likely causes. Even apart from the historical reports you gave, genes that make it less likely to reproduce, even slightly, eventually wipe themselves out; but homosexuality has been observed in many different species. If it was genetic, you’d think that the gene would’ve survived in only a few animals.

I like how Jana introduces biology and culture when addressing homosexuality. I believe homosexuality arises from nature (biology) and nurture (traumatic events). I think the reason why there are not a lot of gay animals is because of their innate motivation to fulfill their needs (finding food, water, competing with other males for reproduction purposes). There are only a few animals that have sex for pleasure.

The difference between us humans and animals is our varying levels of complex thoughts and reasoning. If I was abused by a male, would you understand my preference for a female partner from a nurture perspective? I am no longer thinking about what my future babies with this man will look like, and how much time my biological clock is giving me. Instead, I would be focused on finding a partner who I can trust and love.

The argument “born this way” may have a merit. When I think of sexuality in terms of nature, I imagine hormone levels instead of a gene. When babies are developing in the womb, the levels of hormones dictate whether the baby will develop a Wollfian duct (internal male reproduction organs), or a Mullerian duct (internal female reproductive organs). Varying hormones also cause women to be crabby a certain time of the month, but also contribute to levels of depression, anxiety, etc. Regardless of whether there is a gene or not, I think the nature perspective of sexual orientation is based on differences in chemical levels.

I would also say that love is love, regardless of what you are on the outside. However, the American culture is based on xenophobia and abiding to traditional views. Our culture inhibits us from expressing who we truly are if it does not fall under the norm the society sees it as.

I should have said genetics instead of biology, sorry.

what bothers me the most is from the beginning of time people tried to “understand” why men liked men vs women liking women. We have no idea how it was in ancient times, being in close quarters with someone, being curious or satisfying urges. I for some reason dont understand why its a mystery.

It’s strange to think what biological indifferences there must be between people with different sexual preferences. But why can’t we find this “gene” that varifies whether we are gay or straight? And what so called gene is it when someone is bisexual? I don’t believe it’s a choice, you can’t just wake up one day thinking, “Hey, I’m going to be gay today!” The evidence is just lacking. I’ve never had this sort of conversation with my lesbian sister, but she has had boyfriends in the past. It’s a hard concept to grasp.

You right

I moot point already. What I chose to do, if it doesn’t affect others, doesn’t need discussion. We are beyond the bloody Mary days when making the wrong choice about religion got you roasted.

Maybe I’m not thinking this through, but are there any behaviors that are genetic? I love to cook. Is that behavior in my genes? I never grew up around anyone who particularly cared to cook.

You choosed the life what you want to live

That’s right. We choose to live a way that is honoring to God or we choose to live a life that is not honoring to God. Everyone is free to live however they choose, but we must remember that all decisions have consequences. Man is not an island unto himself.

Reblogged this on creative*Writerz* and commented:

Speech is a choice, thoughts to desires and actions to habits leading to character and then nature. We have a choice to decide what we take from the society, to investigate if our “nature” is not rooted in someone or some group of person’s desired outcome of human lives. Its not my nature to be sexually straight, it is what I choose to believe.

So you believe it is your destiny or nature to be gay? Not that its your nature. The question should now be, is my belief system justified by the standards of requirement for continuance of life, society and the human race.

Is it a duty for us all to prevent extinction of human? Probably dragons fought for gay rights!

You right

Being bisexual myself, I find this to be a very interesting argument. I don’t believe we can choose our sexual orientation, because I remember when I was about seven years old I had a kid “crush” on the girl who worked at the restaurant my dad and I would go to on Saturday mornings. I didn’t choose for it to be that way, and it definitely wasn’t picked up from my environment, because where could I have learned it from? The gay rights movement was pretty much non-existent in my country (and still is) and I was only seven years old, far too young to know what was socially considered right or wrong, plus I grew up in a pretty strict church. My only conclusion is that I was unwittingly “born this way”.

Thank you very much for sharing this well-written piece!

Great post.

Reblogged this on I.. Am.. Kenvincible and commented:

Intriguing article. #Read

I have no trouble in believing that our collective biology in the last forty years has not changed, & the studies carried out by researchers – mainly women – back then discovered that the cause of your sex your sexuality identity and whether your physical gender identity matches your sexual identity is predominately caused by maternal stress, and the stress hormones that wash the growing foetus and interfere with the sexual stamping of the foetus by the production of adrenalin etc., and absorption of these by the foetus.

The process appears to operate in a similar fashion to the process in reptiles like the florida alligator where a change in temperature in the nest of as little as two degrees celcius can alter the sex of the eggs growing there.

Politics has merely accepted what the vast majority of the community instinctively believed, but didn’t know the science behind…

The horrendously complex lives we lead and the unstable work environment only make incompleted sexual stamping more likely and what some believe to be a crime against god is merely (in a simpler time) an aberration.

Our cousins are quite fluid in sexuality (both bonobos and chimps). It seems more of a natural continuum in humans that is expressed differently depending on the culture. It seems more likely that culture determines how strict the boxes are.

This is a very excellent summary! Jennifer Terry’s American Obsession does a wonderful job detailing the emergence of scientific identity politics in the first half of the century in the United States. She, along with Vernon Rosario, have done a very nice job tracing the ways in which biological discoveries shaped, and were shaped by, gender discourses. My own research at Drew University looks into popular publications from the 1930s (Sexology Illustrated, for one) and examines the ways in medicine both popularized normative notions of sexual identity, as well as responded to a culture that was increasingly understanding medicine as a commodity by offering services to either change that sexual identity, or by helping the client “come to terms” with themselves. Ellis was certainly a major departing point for the popular literature that came out in the 1930s, but my work suggests that the “born this way” argument was driven in no small degree by medicine’s desire to carve out markets for “self improvement.” I cannot help but close with a quote from Time Magazine, circa 1945, which I extracted from John Hoberman’s Testosterone Dreams. In it the breathless reporter relays that, “German and Swiss chemical laboratories are already prepared to manufacture from sheep’s wool all the testosterone the world needs to cure homosexuals.”

Regards,

Benson Hawk, JD

Drew University

“You can’t turn gay; you are born gay”

Who can say what percentage of the population this may concern? We may all be bisexual.

I found this fascinating the first time I read it, and a second reading confirms my first impression. All in favor of an alternative, richer and more multi-layered understandings of sexuality

Pingback: WordPressers Making a Splash - WP Creative

Pingback: ‘Pray the gay away’: The Catholic Church, Sexology and Sexuality in Italy | NOTCHES