The sexual and culinary frustrations of summer widowers were a subject of curiosity and conversation in Finland in the first decades of the twentieth century. In stories published in Finnish newspapers and magazines, married men romanticized their days as bachelors in opposition to the constraints and responsibilities of married life. In lines such as “I wish I was still a bachelor…” these husbands expressed a longing for the days when they could still freely flirt with women. The summer widower was usually a middle-class businessman or civil servant who had to remain in the city working while his wife, children, and servants were spending the summer in the countryside. When their families fled to the countryside to avoid the stifling heat of the city, summer widowers might attempt to recapture the erotic possibility of their single days. More often, they found themselves longing for the comfort of their wives’ cooking.

The case of the summer widower exemplifies the complex relationship Finnish men in the early twentieth century had with domesticity. In the words of Martin Francis: “Men constantly travelled back and forward across the frontier of domesticity.” On the one hand, summer widowers fantasized about the sexual and social freedoms typically associated with bachelorhood, yet, on the other hand, the culinary and domestic comforts of a family home stimulated more profound and long-lasting happiness. In 1907, a columnist for the magazine Velikulta described how summer widowers could be found in offices, newsrooms, and banks, yet they spent most of their time in diners, bars, and on the street. Indeed, newspapers, magazines, novels, and short stories, presented summer widowers as spending their evenings with friends in restaurants and clubs, drinking heavily from lunch until the wee hours, and pretending to be unmarried as they flirted with young women. Yet, in contrast to such jolly and erotically tinged scenes, other stories described the misery and difficulties summer widowers suffered in relation to food. While a night out on the town might have catered to the sexual appetites of summer widowers, it left their stomachs unsatisfied.

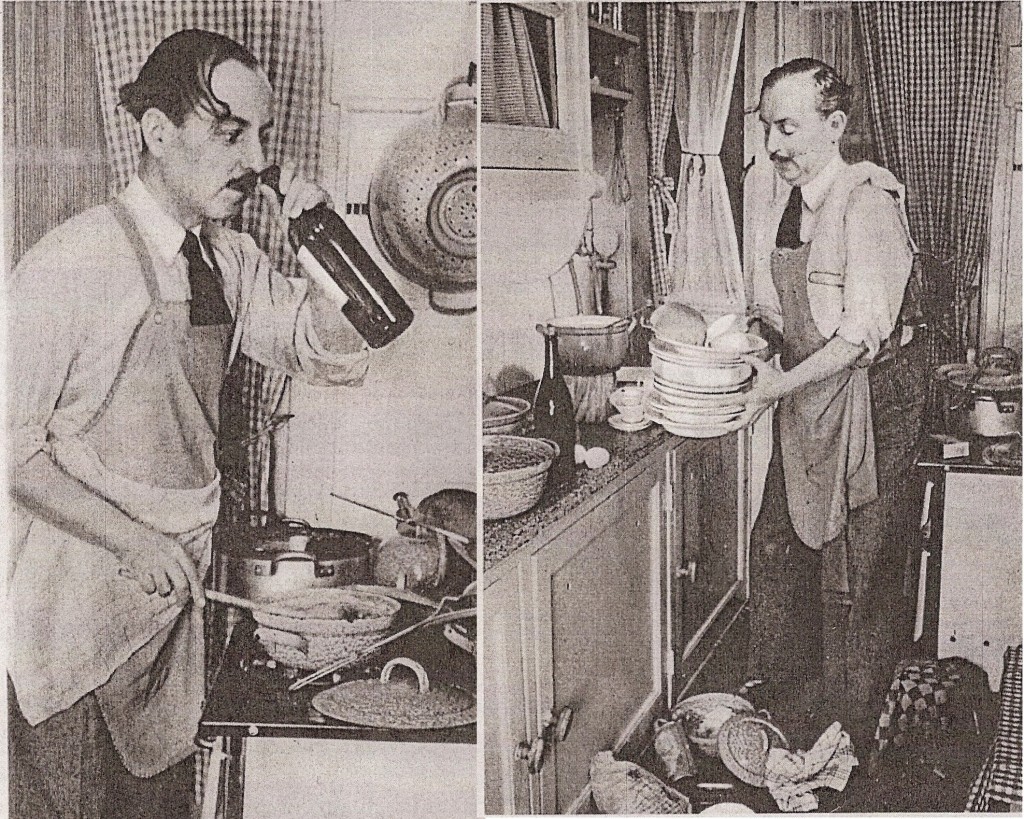

The very name “summer widowers,” instead of summer bachelors, underlined how these men were deprived of the regular home meals that they had grown accustomed to in marriage. When wives left for the summer, these men were forced to eat their meals out in restaurants, diners, or cafeterias. A story titled “Kesäleski” (Finnish for summer widower) and published in the newspaper Aamulehti in July 1921, discusses two summer widowers who decide to cook together. By detailing the hardships of commercial dining – limited options, inconvenient dining times, low quality food and so forth – the story portrays limitations and frustrations summer widowers were thought to suffer. Furthermore, the men’s attempt to cook reveals a desperate and painful longing for the comforts of a home cooked meal. Even when summer widowers were shown voluntarily trying their hand at cooking, the results were usually presented as more a cause for laughter than triumph. Stories in the popular press played up this incompetence with depictions of disorderly kitchens and men unable to warm milk or heat pre-prepared food. Summer widowers’ troubled relationship with food was thus comedic fodder; men, both unmarried and married, were generally not expected to know how to cook.

The mockery extended further, for these men were presented as trying to foolishly relive their youth. A story appearing in 1906 in the magazine Tuulispää highlights such romanticization of past desires as well as how, in the end, reality often kicked in before fantasies could be fulfilled. Nostalgic for their former desirability, the two men’s attempt at a summer fling is cut short by feelings of guilt after one of them denies the existence of his wife and children. The different stories thus presented summer widowers who encountered disappointments and frustrations on both sexual and culinary fronts.

On the other hand, summer widowers’ dining habits became a source of civil concern. In 1919, a member organisation asked the Union of Civil Servants to look into the possibility of setting up a diner for civil servants of Helsinki, who were forced to eat all their meals out. The question was not only about men’s nutrition, however, but also about preventing men from going to taverns and restaurants. Drinking created spaces for non-marital sexual relations and such locales were often frequented by prostitutes. Regulating the food consumption of summer widowers thus came to be seen as one way of protecting men from such temptations.

Summer widowers were thus caught between their culinary and erotic desires: good food and exciting sex were countervailing currents. These men were also bound by the gendered division of labour. Men depended on women for their domestic services and housewives were presented as essential for the everyday well-being of husbands. At the same time, wives were seen as unexciting, unsexy or nonsexual as opposed to young, unmarried women out on the town. Marriage meant having a wife who managed a proper home and made sure food was waiting at the table. Bachelorhood, in contrast, meant being forced to leave one’s home and having less control over the quality of food itself. In the end, summer widowers’ appetite for good food was greater than their desire for freedom or their sexual appetite.

Laika Nevalainen is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy. Her research examines the relationship between Finnish bachelors and home from c. 1880s to the 1930s. In her master’s thesis (2012) she looked at both the aims and the practices of central kitchen buildings that were built in Finland in the 1910s and 1920s. Besides, for example, gender, she sees food as an important part of understanding the meanings and practices of home. She tweets from @PursuitofHome.

Laika Nevalainen is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy. Her research examines the relationship between Finnish bachelors and home from c. 1880s to the 1930s. In her master’s thesis (2012) she looked at both the aims and the practices of central kitchen buildings that were built in Finland in the 1910s and 1920s. Besides, for example, gender, she sees food as an important part of understanding the meanings and practices of home. She tweets from @PursuitofHome.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Hello, Laika

I love your PhD research topic and really enjoyed your article on bachelor behaviour and Finnish summer widowers.

It’s outside your geographical area, but have you read any of the American children’s novelist Laura Ingalls Wilder’s works? She’s fascinating about US pioneer life, including how the many single men working on the railoads and in the shanty towns coped. Also, she’s slowly becoming academically interesting. Big, well-referenced books have been written :>) Check out:

https://lammylou.com/little-house-pancakes/

https://wikilivres.org/wiki/Laura_Ingalls_Wilder

Good luck with the PhD.

IFAW_Camino_2019@2019Ifaw (Twitter)