Late on a Monday evening in November 1934, the Columbia Broadcasting Service (CBS) made a last minute decision to censor the Health Commissioner of New York state, Thomas Parran, from a national radio broadcast. He refused to remove the word “syphilis” from his planned talk on public health work, so audiences heard music rather than the latest installment of “Doctors, Dollars, and Disease.” In the wake of incident, the New York Post published a scathing criticism of CBS’s actions:

Some one ought to take the radio executives by the hand and gently break the news to them that the dear, sweet, smirking Victorian days are dead. We have reached the stage where we can hear the truth without falling in a dead faint, and we are as anxious to fight one disease as another.

Many other commentators also highlighted the hypocrisy of the “false modesty” at the root of this act of censorship. Avoiding public and frank discussions of venereal disease (VD) control in the name of propriety and morality only made an already serious problem worse, they argued. In this era, syphilis was estimated to affect more than 10% of the population at some point in their lives and 2-4 times as many people would contract gonorrhea. Before routine testing or antibiotic treatment, many who were infected would go about their lives unaware of their illness until they developed sterility, heart disease, paralysis, blindness, insanity, or died from the complications.

In spite of the prevalence and seriousness of these illnesses, VD had often been a taboo topic because it was associated with marginalized groups such as African Americans, prostitutes, sailors, and the working poor. Moreover, VD was often associated with immorality or hypersexuality. When the issue was addressed, it was couched in euphemisms such as “social disease” or “moral hygiene.” The negative meanings attached to these illnesses also promoted disinvestment in public health efforts to control them, even as there were a flurry of important discoveries in VD control in the 1910s.

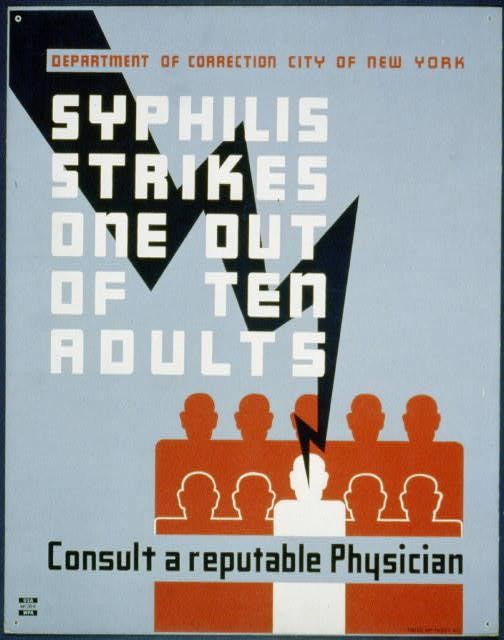

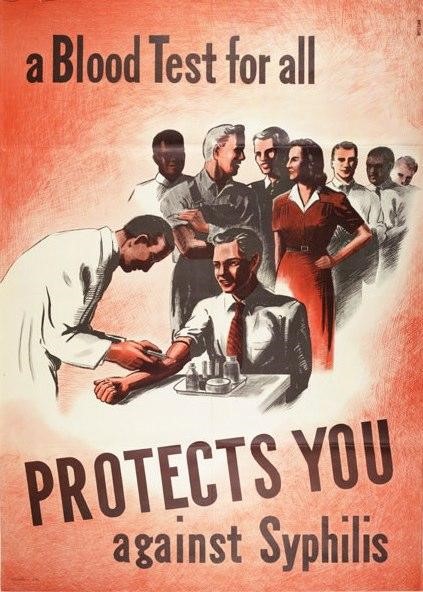

However, the support for Parran in the wake of the CBS debacle, and his appointment to the position of Surgeon General of the US Public Health Service (PHS) in 1936, was an indication of change. During the 1930s, VD control became integrated into the everyday life of Americans in an unprecedented way. People saw posters about venereal disease in libraries and on the subway. The topic appeared in popular magazines and newspapers. Across the nation, people attended productions of the Federal Theater Project play Spirochete (1938) and showings of the Warner Brothers’ film Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940), which both centered on the history of syphilis and its control. At the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940, millions of visitors viewed exhibitions on the issue. By 1944, thirty states had passed laws mandating pre-marital and pre-natal syphilis testing. As a result, the first mass blood testing Americans ever underwent was for syphilis as they applied for marriage licenses or prepared for the birth of a child.

There was not only a new openness about discussing VD control, but also changed attitudes specifically about the role of the state in developing a more robust public health program. Gallup Polls in the 1930s and 1940s revealed that large majorities of Americans (70-92%) were supportive of the premarital testing laws, government clinics and education, free testing for anyone regardless of income, and massive appropriations to make public health programs possible. In 1938, Congress unanimously passed the National Venereal Disease Control Act, appropriating up to $3,000,000 for anti-VD public health measures, increasing funding each year, no small feat during the Great Depression. By the 1940s, the federal government was spending over $10,000,000 each year on these efforts targeting civilians in addition to the money spent to educate, test, and treat servicemen. Many states matched or superseded federal funding to help develop their programs. With these appropriations, hundreds of clinics were opened, millions of free tests and treatment injections were provided to citizens, and educational efforts expanded.

The increased visibility and scale of VD control was part of a concerted effort to “stamp out” syphilis (and later gonorrhea), led by Surgeon General Parran and the PHS, that lasted through the end of World War II. Overwhelmingly the main emphasis was to routinely test every American for syphilis and then cure people or render them noninfectious through chemotherapy (a “chemical quarantine”). This was a shift from previous approaches that focused on physical quarantines, targeted marginalized groups, or relied on local government or voluntary organizations to deal with the issue.

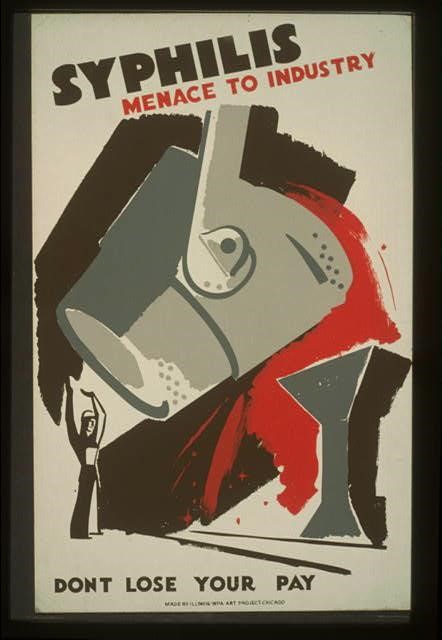

There were a number of reasons VD control gained momentum in this era. One was the leadership and legitimacy Parran brought to the issue as Surgeon General and a well-known public figure and medical authority. Other influences were related to broader social and cultural changes of the era. The campaign tapped into concerns about families and social stability, the health of servicemen and workers, and economic performance that were salient to the American people in the context of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt’s New Deal, and World War II. An interest in social planning and state interventions in this era, seen not just in this campaign and New Deal programs, but also the movements for birth control and eugenics, also fortified support for Parran’s efforts. The images and themes used by the campaign also moved the issue away from questions of sex and morality, to minimize the more controversial elements that reformers felt had held back previous anti-VD work. Parran and his partners wanted to make VD an infectious disease like any other that could affect any American regardless of background. Ultimately, they argued, the strength of families, communities, and the nation depended on cooperation between government and citizens to eradicate these illnesses.

Materials often focused on the social and economic costs of ignoring VD and emphasized the benefits of being proactive about controlling it. Children with congenital syphilis, broken families, handicapped workers, and those impoverished by medical bills became the symbols of continuing along the path of “false modesty.” In contrast, images of cheerful workers and families were associated with not only health, but also participation in the anti-VD campaign. If people adhered to the recommendations of medical professionals, they would lead happy, healthy lives.

This reflected a confidence in modern medicine that was apparent throughout the campaign and in popular culture more broadly. Spirochete, for example, contrasted the ignorance and futility of historical approaches to syphilis with the great scientific discoveries that led to the treatment and testing methods available in the 1930s. VD could and should be “stamped out” now thanks to heroic scientists, who became another positive symbol of the program. Though the campaign sometimes used fear or melodrama to emphasize the seriousness of the situation, overwhelmingly the final word was one of optimism: syphilis would be “the next great plague to go.”

Campaign materials also emphasized that the negative effects of these illnesses impacted the whole community, not just individuals with VD. This helped legitimize a stronger role for government in the program and spending tax dollars on the issue. Workers who developed complications with motor skills might not only lose their job, but also decrease industrial efficiency or harm others if they caused an accident at work. In the midst of the Great Depression, concerns about national recovery hit home with Americans. Additionally, a sick worker not only failed to be a proper breadwinner for his family, but also became another person added to the swollen relief rolls or committed to a public institution for the blind or insane. Later, as the US mobilized for war, industrial strength was seen as key to defeating the Axis, again tying the fate of the nation to individuals’ behavior.

Many of these themes were also seen in the movements for eugenics and birth control, which underwent some similar shifts in the 1930s and 1940s. The authority of medical professionals, the importance of health and family planning interventions for the less fortunate and the middle class, and the social and economic benefits for society as a whole were highlighted in all three. The anti-VD campaign’s use of similar arguments and symbols may have tapped into the public’s existing familiarity with these discourses. And, participation in venereal disease control could have been viewed by some Americans as one component of these broader family and social planning agendas that tied personal decisions to the health and success of the community, race, or nation. Like the anti-syphilis campaign, these ways of framing birth control and eugenics not only appealed to the public in the context of depression and war, but also distanced these issues from sexuality and morality (and hopefully controversy).

While the approaches taken by the anti-VD campaign surely increased access to health care for many Americans, there were some limitations to this approach that avoided the more difficult and controversial issues related to control of venereal diseases (such as condom use, extramarital sex, child abuse, and racism), rather than interrogating them. Therefore, in spite of the wild success of growing infrastructure and public awareness in the 1930s, the long term results of the campaign were more ambiguous. For example, reliance on only routine testing rather than also publicizing prevention via condoms limited the effectiveness of the program. Though condom use was promoted among servicemen, “mechanical prophylaxis” was too controversial for the mainstream campaign to endorse because of the condom’s other function as a method of birth control. (Parran and other New Deal officials never publicly endorsed birth control.) As a result, treatment, rather than prevention, remained the standard approach.

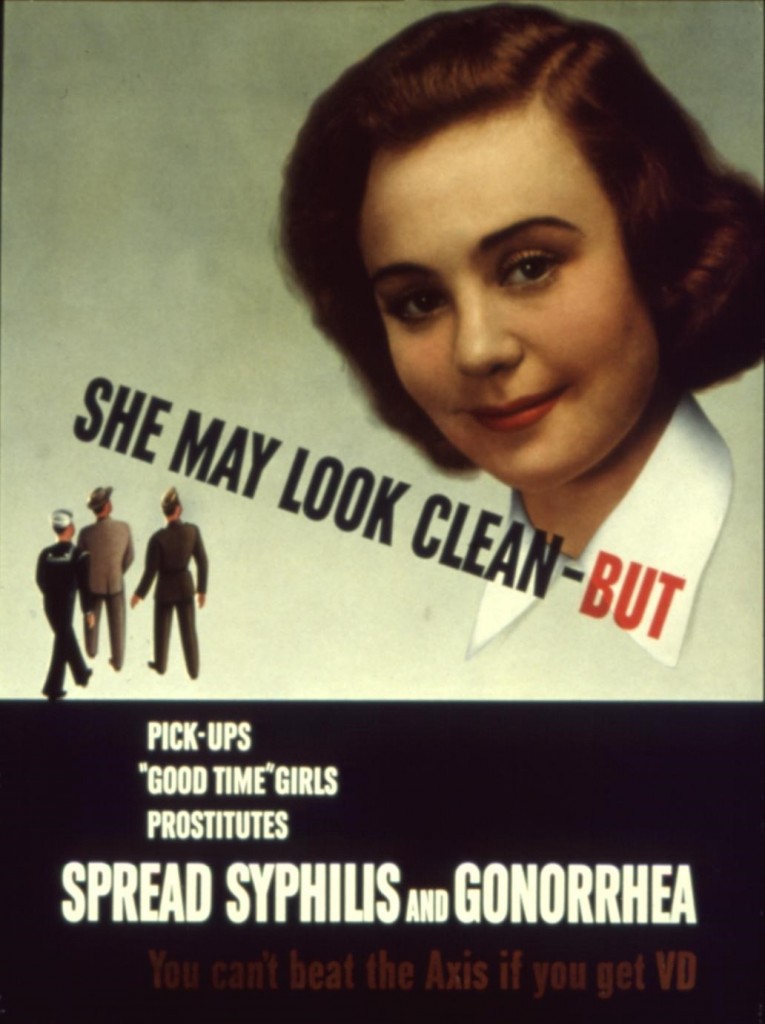

Stereotypes about the immorality or hypersexuality of African Americans and women continued to plague these efforts in particular. Assumptions about the limited intelligence of black patients shaped media coverage of programs serving black communities, as well as educational materials created for black audiences (which sometimes presented questionable information). The PHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee—where the agency lied to and withheld treatment from poor, black men with syphilis with the goal of “studying” the long-term effects of syphilis—continued under Parran’s tenure even as he was publicly vocal about support for legitimate health care for black communities. This in particular has become the symbol for unethical medical practices in the US, as well as a popular touchstone in the history of VD.

As Amanda Littauer addressed in a previous post in this series, WWII led to increased concern about women’s sexual behavior. VD discourse and policy now focused on policing the social-sexual behavior of all women, who were sexualized and seen as potential vectors of venereal disease. They became dangerous threats to the war effort. This gendered and moralizing rhetoric, which had purposefully been avoided a few years earlier in the 1930s VD campaign, was central to professional and popular coverage of the issue. It built on earlier medical, social science, and eugenic discourses that linked hypersexuality, juvenile delinquency, and “feeblemindedness” in women. This focus on women as vectors not only revealed cultural anxieties about the sexual freedom of young women, it also helped legitimize their forced incarceration at Rapid Treatment Centers across the country where they were treated for syphilis and gonorrhea. Though this emphasis on problematic sexual women contrasted the 1940s rhetoric from the 1930s, the role VD control played in strengthening the family and preserving the health of industrial workers continued to be salient and was prevalent in wartime VD propaganda.

In the 1930s, Parran and his partners in the national campaign to control syphilis created new meanings for VD that distanced it from immorality, illicit sex, marginalized groups, and instead tried to paint it as an infectious disease like any other that affected all types of people. In doing so, they attempted to take the “venereal” out of venereal disease, to gain support for what had previously been a taboo issue. While wildly successful in creating awareness and support, simply trying to desexualize VD without addressing more complicated issues related to race, gender, and morality ultimately limited the effectiveness of the campaign and resulted in unethical attempts at targeting those who continued to be seen as “reservoirs of infection.” Today, many Americans are still having the moral-medical debate about everything from insurance coverage of birth control to HPV vaccines. If the 1930s campaign can impart any useful lessons, most important seems to be that long-term progress in promoting sexual health does not come by taking sex out of the conversation.

Erin Wuebker is an historian who specializes in public health, visual culture, and women, gender, and sexuality. Her research focuses on the campaign to “stamp out” venereal disease in the US in the 1930s and 1940s. She created the Venereal Disease Visual History Archive, which focuses on American materials related to VD from the early 20th century. Currently she teaches at Queens College and works at the Museum of the City of New York and Brooklyn Historical Society. She tweets from @erinewuebker.

Erin Wuebker is an historian who specializes in public health, visual culture, and women, gender, and sexuality. Her research focuses on the campaign to “stamp out” venereal disease in the US in the 1930s and 1940s. She created the Venereal Disease Visual History Archive, which focuses on American materials related to VD from the early 20th century. Currently she teaches at Queens College and works at the Museum of the City of New York and Brooklyn Historical Society. She tweets from @erinewuebker.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thank you very much for your work. I’m writing a novel set in the 1930s-50s and syphilis is an integral part of the plot. If you have a newsletter, please subscribe me at: tamelarich@gmail.com