Interview by Rachel Hope Cleves

Rachel Hope Cleves: What do lawyers look for from historical testimony? What role does historical evidence play in gay rights cases?

George Chauncey: The courts have found historical evidence useful in a variety of ways. Nancy Cott, for instance, played an important role in marriage equality litigation by explaining how marriage has changed many times before, in ways that once seemed as threatening as allowing same-sex couples to marry, in response to changing social and political conditions. In most of the cases I’ve participated in, beginning with my testimony in Romer v. Evans in 1993, I’ve focused on the history of antigay discrimination. Establishing that history is important because it affects the level of scrutiny a court applies to a law singling out a group for distinctive treatment when it’s trying to decide if the law violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The state distinguishes among citizens all the time, and normally it only has to show that there’s a rational basis for the distinction between, say, the licensing requirements for the operator of a passenger car and an eighteen-wheeler. But when a group has experienced a history of discrimination and has not had the political power to defend itself, the courts may feel obliged to subject a law to heightened scrutiny when it singles out that group, for instance by excluding its members from marriage.

Even when a court isn’t prepared to subject antigay legislation to heightened scrutiny – some federal and state courts have, most have not, and various levels of “intermediate scrutiny” are emerging – it’s been useful for the courts to learn about this history because it places present-day discrimination in a larger historical context and makes the rationales for it seem less persuasive. And you can definitely see how this historical context has influenced the decisions reached by some courts.

I’ve also testified about the history of antigay demonization. This was especially important in the 2010 Perry trial, where I explained in my courtroom testimony how the messaging strategies of the Prop 8 advocates relied on a much longer history of antigay demonization, from the solidification of the image of homosexuals as child molesters in the 1950s, to Anita Bryant’s 1977 “Save Our Children” campaign, to the antigay videos and literature circulated during the anti-gay-rights referendum campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s, including the 1992 Amendment Two campaign in Colorado, which was at issue in Romer. It was deeply heartening to read the judge’s opinion in Perry and see him accept and explicate the argument I’d made about how the Prop 8 campaign could be more subtle in its “Protect Our Children” messaging strategy precisely because one legacy of earlier antigay campaigns was that they did not have to be as explicit about what children had to be protected from.

In Lawrence v. Texas [2003], the point of our amicus brief was somewhat different. It was to show the Court that the historical rationale the Court had used to help sustain the constitutionality of sodomy laws in Bowers v. Hardwick [1986] was incorrect. We provided the court an alternative interpretation of the history of sexual categories and sexual regulation, and showed how the Texas homosexual conduct law under review in Lawrence was a product of a new regime of antigay discrimination in the twentieth century, rather than the product of “millennia” of antihomosexual teaching, as the Chief Justice had averred in his Bowers concurring opinion. The Court devoted a large portion of its Lawrence decision to questions of history, and it was incredibly rewarding to see how much significance a historical argument could have.

RHC: How did you first come to testify as an expert witness in Romer v. Evans back in 1993? Did the legal team approach you?

GC: Attorneys from Lambda Legal approached me about testifying in Romer. I’m not sure why they asked me, since I was still a beginning assistant professor at the University of Chicago and had not yet published Gay New York, although I had published several articles and co-edited Hidden From History, an early anthology of historical essays. Being an expert witness requires a very particular skill set, and since Romer, attorneys working on a range of cases have asked me to become involved in their cases.

RHC: What does an expert witness do? How often does your testimony take the form of writing?

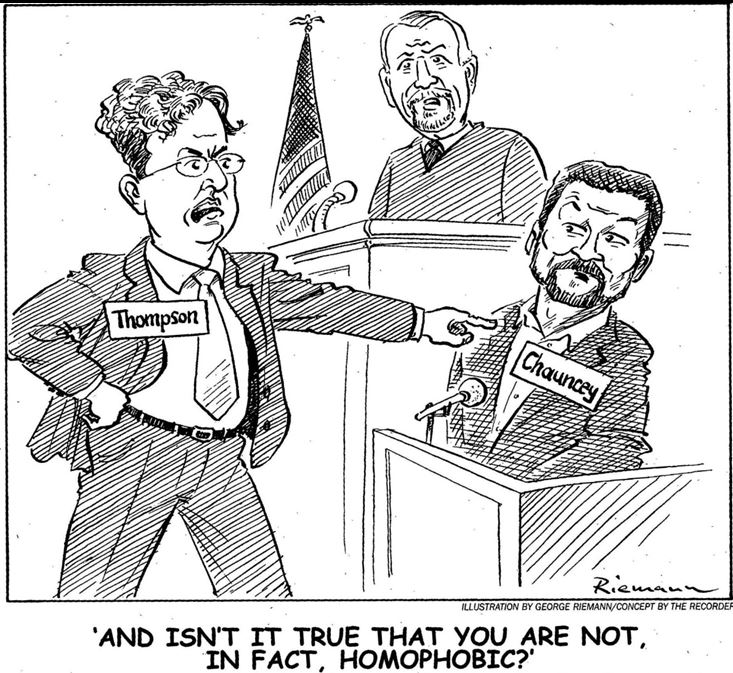

GC: An expert witness is someone with professional knowledge of facts that may bear on a court’s decision in a case. The judge has to certify you are qualified to be an expert, usually based on your publications, academic appointments, and other scholarly credentials. The opposing attorneys can challenge your credentials. They have always accepted mine, although that hasn’t stopped them from trying to challenge and undermine my testimony.

I’ve participated in cases in a variety of ways. The most demanding cases have been the ones in which I’ve testified at a trial. Before the trial, a witness has to submit a report to the court which outlines all of the facts you’re prepared to testify to. That’s then given to opposing attorneys and is the basis for your deposition, a sort of pre-cross-examination, in which they probe the extent of your knowledge and where they may be able to challenge your testimony. My deposition in the 1993 Romer case lasted two full days, and it lasted most of a day in Perry. I was also deposed in Windsor and a number of other cases that never went to trial but were decided by summary judgment.

As you can imagine, testifying in a courtroom is the most demanding and stressful experience. I was on the witness stand for six or seven hours in the Perry or Prop 8 trial in San Francisco in 2010. The best analogy for an academic is that testifying is a bit like taking your orals: you have to be ready to answer any question and never can be sure where the questioning will go. Except that during an oral exam, you know that the people asking you questions have your best interests at heart and want you to succeed, which is not exactly the case in cross-examination. To add to the pressure, the Perry trial got so much publicity that a couple of dozen people in the audience were blogging everything the other witnesses and I said, or at least what they thought we said.

But most cases don’t go to trial, and are decided instead by the judge in a summary judgment. I have submitted sworn affidavits or declarations about the history of antigay discrimination in more than a dozen such cases, including cases challenging sodomy laws, the military ban, and adoption bans, as well as the more recent round of cases challenging the exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage.

In still other cases I have prepared “friend of the court” (amicus) briefs. In Lawrence v. Texas, I organized and was the lead author on the Historians’ Amicus Brief, which nine other historians joined and worked on. In Windsor, Perry, and Obergefell, I drafted the amicus briefs submitted to the Court by the Organization of American Historians. I’m so grateful that the OAH’s leadership was willing to submit these briefs, which gave the association’s imprimatur to a generation of scholarship produced by their members working in the field.

RHC: How much research goes into your time on the stand?

GC: In a legal proceeding, you have to be absolutely certain of your facts and your interpretations, because the other side will challenge you in any way they can. I always rely on and cite my own research and the work of many other historians, of course, and in preparation for depositions or trials I’ve re-read and studied some key historical studies and primary documents countless times. Sometimes I’ve needed to do additional research on discrimination in a particular state where a case is based, or I’ve asked research assistants to track down relevant newspaper stories and the like, but I’ve always had to examine them closely to see how — and if — I want to draw on them in a declaration. Teaching has also helped me prepare for testimony, since answering my students’ questions has helped prepare me to answer lawyers’ questions. There’s been an incredibly productive synergy between my preparation for these cases and for the large lecture course on US Lesbian and Gay History I teach every fall at Yale.

RHC: Over the course of your long involvement in the legal struggle for gay rights, you’ve testified in cases ranging from challenges to anti-sodomy statutes, to cases related to discrimination, to cases connected to same-sex marriage. Can you talk a little about how the cases you’ve participated in have changed over time? What hasn’t changed?

GC: In Romer and the other early cases, the opposing attorneys tried to challenge the assertion that there was a history of antigay discrimination. That wasn’t a very successful move on their part. Nowadays they don’t try to deny the existence of this history, since it’s come to be generally known and accepted in the last twenty years due to the work of many, many historians. But it’s still vitally important to describe the extent and periodization of antigay discrimination, and the manifold forms it has taken, since judges are no more likely than other non-specialists to know this history. In recent cases, the opposing attorneys have usually tried to argue that discrimination is, well, history, that it’s all a thing of the past. So I try to show how and why things have changed, but also how much discrimination persists and how much we still live with the legacy of the harsher discrimination and demonization of the past.

RHC: Robbie Kaplan, the lawyer who represented Edie Windsor in United States v. Windsor, has stressed the importance of emphasizing personal stories in the legal struggle for gay rights. Have you found this to be true? And if so, how does that effect the public conceptualization of gay rights?

GC: Almost all lawyers involved in impact litigation try to find plaintiffs with compelling stories. I don’t think this is so different from what historians do when we try to make our arguments about broad historical processes more compelling by telling vivid stories about how those processes affected particular people. Most civil rights lawyers try to use their cases to influence the public debate as well as the law itself. And they know that abstract claims about the legal security provided by marriage, for instance, are less compelling than the story of a particular person, such as Robbie Kaplan’s plaintiff Edie Windsor, who would have lost the home she’d bought with her partner of 40+ years if she hadn’t been able to pay the enormous inheritance tax she was charged, and would have been spared if the federal government had recognized the marriage they had traveled to Canada to secure. But this also means plaintiffs bear a significant representational burden. Most gay rights litigators file cases on behalf of a group of plaintiffs rather than a single person, since their stories collectively can convey the racial and class diversity of gay life, as well as the multiple harms caused by discrimination.

RHC: When did you become convinced that same-sex marriage could be legalized in the United States?

GC: I wasn’t confident about the outcome of the marriage litigation for a long time, even though I came to have enormous respect for the strategic intelligence, capacious social vision, and sheer brilliance of the attorneys I worked with on these cases, such as Mary Bonauto at GLAD, James Esseks at the ACLU, and Susan Sommer at Lambda Legal. But Justice Kennedy’s opinion overturning the Defense of Marriage Act in Windsor in 2013 made me think the Court would ultimately find gay couples had a constitutional right to get married. The constitutional reasoning in his decision, even though it was narrowly tailored to invalidate DOMA, made it clear that denying same-sex couples’ access to marriage was constitutionally impermissible, and this is how almost every district and appellate court interpreted his opinion when deciding the tidal wave of cases following the Windsor decision. That said, I don’t think Justice Kennedy expected to have to hear another case so soon after Windsor – he basically said as much from the bench during oral argument. Nor did most of the major litigators expect another marriage case to reach the Court in just two years. But the tide had turned and the historical momentum was so strong that it forced the Court to act more quickly than anyone expected.

RHC: What has been most rewarding – and frustrating – about being involved in these cases?

GC: The most frustrating thing is that working on these cases has delayed my next book, the long overdue sequel to Gay New York, so much. It’s hard to convey how many school nights and weekends I’ve spent preparing declarations for cases, especially in the last five years. But at the same time, of course, it’s been incredibly rewarding to be able to intervene in public policy debates as a historian, something I never imagined I would be asked to do when I was a grad student. And being required to craft a sweeping narrative of sexual regulation from colonial times to the present has been an unexpectedly productive pressure. It was really only when drafting the Lawrence amicus brief in 2003 that I fully grasped how profound the shift was from the regulation of sexual conduct in the 19th century to the emergence of a 20th century regime in which the state classified and discriminated against some of its citizens on the basis of their status or identity as homosexual, an argument I later developed in my short 2004 book Why Marriage? I’ve also learned so much from these cases about how the law works, which has benefitted my scholarly writing. And my teaching. Last fall I co-taught a course at the Yale Law School with Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel on the development of reproductive and LGBT rights law in the fifty years since Griswold, something I wouldn’t have contemplated doing before being involved in these cases.

RHC: What do you think about the current legal battles being fought over transgender bathroom access rights? Would you dare to make a prediction about the outcome of this battle? What are some of the other new frontiers in litigation likely to be?

GC: There are so many issues still facing LGBT people, but many of them will not be settled by litigation. The fact that trans people encounter so much violence and ridicule, that 40% or more of homeless youth are queer, that HIV infection rates remain shockingly high, and that so many queer kids still face harassment in schools are pressing issues that need to be addressed primarily outside of the courts. But the fact that the Supreme Court has issued a series of decisions in the last twenty years affirming the dignity and equal rights of lesbians and gay men makes me fairly optimistic that the argument conservative religious activists are making that the principle of religious liberty should somehow allow them to continue to discriminate against gay people will ultimately be unsuccessful. The recent decisions also leave me fairly optimistic that litigation challenging anti-trans discrimination, including in restroom facilities, will also be successful. That said, most of the recent Supreme Court cases were decided by one vote, so a lot depends on who is sitting on the Court in the coming years.

George Chauncey is Samuel Knight Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, and author of the groundbreaking work, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (Basic, 1994). He has testified as an expert witness in more than thirty cases dealing with gay rights, five of which have come before the Supreme Court of the United States. Chauncey testified or was deposed in all three marriage equality cases decided by the Court in 2013 and 2015. For the one-year anniversary of the Obergefell vs. Hodges decision, we interviewed Chauncey about his experiences with the courts.

George Chauncey is Samuel Knight Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, and author of the groundbreaking work, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (Basic, 1994). He has testified as an expert witness in more than thirty cases dealing with gay rights, five of which have come before the Supreme Court of the United States. Chauncey testified or was deposed in all three marriage equality cases decided by the Court in 2013 and 2015. For the one-year anniversary of the Obergefell vs. Hodges decision, we interviewed Chauncey about his experiences with the courts.

Rachel Hope Cleves is a Professor of History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She specializes in early American history and has written about the history of same-sex marriage and about American reactions to the French Revolution. Her most recent book is Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford University Press, 2014). She is presently at work on a book project titled “Good Food, Bad Sex.” You can follow her on twitter @RachelCleves.

Rachel Hope Cleves is a Professor of History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She specializes in early American history and has written about the history of same-sex marriage and about American reactions to the French Revolution. Her most recent book is Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford University Press, 2014). She is presently at work on a book project titled “Good Food, Bad Sex.” You can follow her on twitter @RachelCleves.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com