Moderated by Lauren Gutterman

Following up on a 2017 American Historical Association conference panel, “Queering Femininity: Gender Normativity and Lesbian History,” we invited Alix Genter, Anastasia Jones, Amanda Littauer, Shannon Weber, and Cookie Woolner to participate in a two-part roundtable on femme histories. In part one, these scholars discussed the extent to which female masculinity continues to dominate lesbian and queer women’s history, as well as the findings of recent scholarship focusing on feminine queer women. In this second and final installment of the series, our roundtable participants draw on their own work to suggest how studying the history of femmes has broader implications for the history of sexuality.

Can you offer some examples drawn from your work that demonstrate how the experiences of feminine lesbians or queer women might change our understanding of the history of sexuality?

Cookie Woolner: In my research on African American women who loved women before Stonewall, sexology case studies are one of the few available sources that allow me to access the actual voices of the historical actors in my work. While the primarily white male doctors who studied the science of sex in the early- to mid-twentieth century moralized over and pathologized their black queer subjects, they also interviewed at length the women they analyzed. While it’s difficult to confirm the veracity of many of these interviews, they nonetheless offer unique insight into the lives of femmes in this time period. Following the work of lauded European sexologists Havelock Ellis and Richard von Krafft-Ebing, American sexologists generally delineated feminine queer women as the passive victims of aggressive and predatory masculine women’s advances. However, the experiences of the femmes they interviewed sometimes told a different type of story.

One of my favorite examples appears in the 1941 study Sex Variants, which recounts the case study of a woman given the pseudonym Susan, “a tall, slender, languorous woman of twenty-six” who the doctors say “has an admixture of negro blood which gives her an exotic and seductive air.” The researcher notes that in “manner, bearing and allure, Susan is feminine. She is, however, remarkably at ease and purely objective in giving an account of herself.” She recalled of her childhood, “in school I was very devilish. I played with girls’ curls and annoyed everybody in the class. I wasn’t a tomboy and I liked fluffy clothes and the typical girlish games and pleasures.” When it comes to sex, Susan declares, “it’s more pleasurable and more complete when I’m taking the active part. I like girls who have lots of experience. It saves a lot of trouble.” And lastly, Susan proclaims, “If I were born again I would like to be just as I am. I’m perfectly satisfied being a girl and being as I am. I never have had any regrets.”

This biracial femme’s assuredness and self-possession were probably not unique, yet such representations are hard to come by. Susan’s comfort with her sexuality and her interest in taking an “active” role during sex are qualities many would associate with lesbian self-expression since the 1970s rather than the mid-1930s when the interviews for Sex Variants occurred. While the white male doctors of the study sought to tie her ability to “seduce” others to her “admixture of negro blood,” playing on longstanding tropes of Black women’s licentiousness, Susan does not appear ashamed of any aspect of her identity. Further, her apparent pride in her gender and sexuality – decades before the gay liberation and black feminism movements – also pushes back against the stereotype that African American communities have historically been less accepting of queerness than other racial groups. While classic texts like Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold focused on communities where feminine queer women usually took a “passive” position sexually, case studies like Susan’s reveal that some early- to mid-twentieth century femmes had a different relationship to gender, sex, and power.

Anastasia Jones: My work addresses popular conceptions of female same-sex intimacy and desire in U.S. interwar culture. I embarked upon my research with full awareness of the gospel of the “mythic mannish lesbian.” But if I expected to devote much of my attention to masculine-leaning women, I was almost immediately surprised. I perused a broad range of sources, from erotica and novels to psychological and sociological studies, from films and tabloids to diaries and letters. And as I did so, three things became increasingly apparent. In the first place, sex and intimacy between women was a source of almost endless discussion and speculation during the interwar period. Secondly, a range of women were thought to engage in same-sex relationships. The range was broad enough, in fact, that I subdivide the panoply into four (overlapping) categories: “college girls,” married women, juvenile delinquents and criminals, and women in the urban entertainment industry. And thirdly, remarkably few of these women were understood as masculine—or even lesbians.

A couple of examples: Women affiliated with urban show business subcultures were frequently portrayed (especially in the tabloid press) as feminine, sexually fluid, and, in many instances, mercenary, duplicitous, and even predatory. Such women were thought to profit from their traditional sex appeal, even as they sought and secured female lovers. Because these women were immersed within entertainment industry milieus, their homosexual inclinations were understood as barely-veiled secrets: apparent to subcultural “fellow travelers,” but invisible to clueless outsiders.

“College girls” with homosexual inclinations, meanwhile, were frequently represented as both overly—nefariously—feminine and socially delayed. Drawing on both popular advice columns and the era’s spate of melodramatic “college girl” novels (an interwar subgenre), I show that variety of cultural observers and commentators appeared to worry that the excessively “girlish” environments of women’s college campuses inculcated psychological rot amongst college girls: emotional and sexual maladjustment. The college girl with a “mash” on her best girl chum was seen as the embodiment of twisted female innocence.

Tabloids, questionable novels, gossip: this research is fun. But it’s also important. Paying attention to feminine, lesbian-leaning women highlights the extent to which female homosexuality was woven into the interwar social fabric. Female same-sex desire was imagined as a constant that had the potential to affect every woman, rather than an anomaly that delineated a minority. Female same-sex desire, in other words, was not something that required masculinity for social legibility; nor was it seen as uncommon—or insignificant. The malleable frame of female homosexuality served as a framework for a wide-ranging social discussion regarding the shape and tenor of modern culture during the era. But the import of the womanly chorus girls and feminine college girls from the pages of my research extends beyond the interwar period. Based on the research being conducted by, among others, my colleagues on this roundtable, it seems likely that these feminine and flexible challenges to the homosexual-heterosexual binary shaped the sexual and social fabric well past the 1930s.

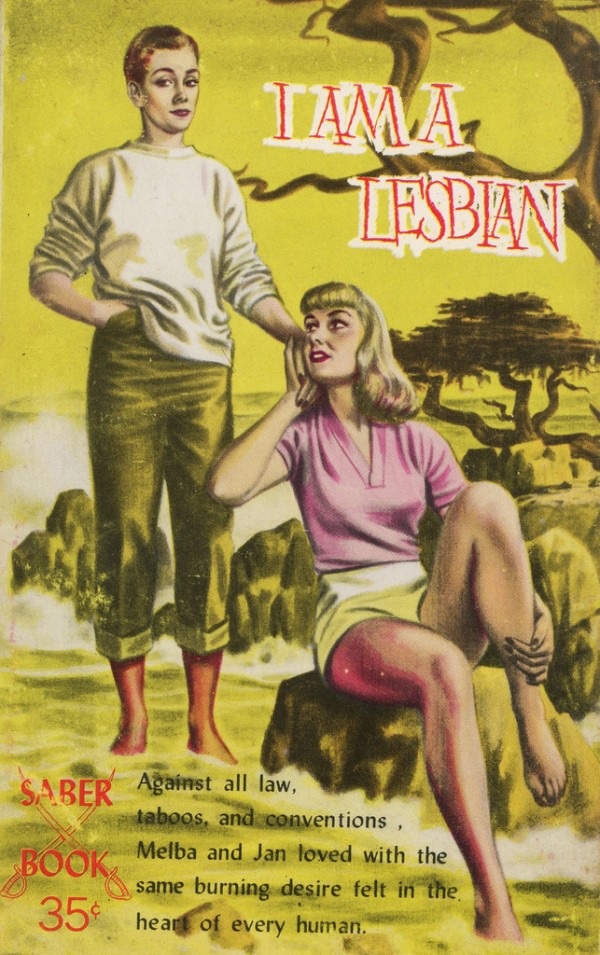

Alix Genter: My research explores butch-femme lesbianism in the mid-twentieth century United States, arguing that gendered identities, rituals, and relationships were the primary cultural institution among queer women. Lesbian author Ann Bannon presents a window into this world in The Beebo Brinker Chronicles, a six-book paperback series published between 1957 and 1962. The books’ popularity at that time and their reclamation starting in the 1980s have made them a familiar source for historians and literary scholars alike. Many analyses focus on the political and cultural implications of Bannon’s contribution to lesbian literature, or on Beebo herself, Bannon’s confessed butch fantasy. But the series also offers keen insight into femme subjectivity. While Beebo finds acceptance of her boyish body in a lesbian bar community, transforming her lifelong shame into pride, Bannon’s femme character, Laura Landon, struggles to reconcile her queer desire with her femininity. Scared and confused after giving in to a kiss from another woman, Laura sobs while inspecting her appearance:

Nothing seemed wrong. She had breasts and full hips like other girls. She wore lipstick and curled her hair… [E]verything was feminine… She thought that homosexual women were great strong creatures in slacks with brush cuts and deep voices… She looked back at herself… and she thought… “I’m a girl. I am a girl… But if I’m a girl why do I love a girl? What’s wrong with me?” (Odd Girl Out, 1957)

Laura’s femininity confounds her understanding of lesbianism—still inextricably tied to “mannishness” in the world in which she lives. This painful uncertainty created a form of misembodied, gendered shame that resonated beyond the pages of fiction. Femmes were literally unable to embody quintessential lesbianism, while their unruly queer desire and non-marital erotic exploration simultaneously distanced them from dominant ideologies of womanhood.

For many femmes negotiating this liminal space, sex was the arena that ultimately provided a sense of both queer belonging and a gender identity to replace the normative category “woman” that eluded them. In a culture rooted in and sustained by sexuality, femmes were the focus of erotic attention in queer communities. Being pursued, fucked, and sexually fulfilled by a butch was often a core component of femme identity; they loved the feeling of being, in Amber Hollibaugh’s words, “the woman that a woman always wanted.” In addition, butches’ immense pleasure in pleasing their lovers could ease femmes’ shame at simply being sexual women in postwar America. As Lyndall MacCowan explains, “It is butch women who made wanting sex okay, who never said I wanted it ‘too much’ or thought I got too wet.” Embracing their sexuality was one way that femmes managed the complicating factor of their gender normativity, created distinct identities, and asserted themselves as queer beings.

Scholars of feminist and queer studies quickly learn to uncouple gender and sexuality, firmly distinguishing between anatomical sex, gender, and sexual orientation. But a look at postwar femmes demonstrates that sexual subjectivity and gender always inform one another and cannot be disentangled. Just as whiteness does not constitute racial neutrality, normative gender presentation does not constitute gender’s absence. Femme identities combine gender and eroticism and are interpreted in diverse ways, and femmes’ experiences do not mirror those of similarly gendered straight women. Examining female femininity, and not only female masculinity, reveals the unique and varied ways that queer women have manipulated gender ideologies to produce a multiplicity of queer, gendered subjectivities in the lesbian past and present.

Amanda Littauer: In my current research on queer youth, I have found rich accounts of same-sex desire and intimacy among feminine girls that challenge familiar developmental and historical narratives. One of the clearest ideas to emerge so far is that femininity allowed girls to fly under the radar of adults and other youth. This invisibility had its benefits, such as allowing girls to escape the gender-policing harassment and violence experienced by gender nonconforming youth, and also to explore erotic friendships and sexuality. Parental obliviousness to the sexual elements of their daughters’ same-sex friendships is a prominent theme in lesbian oral history narratives from the mid-twentieth century. For instance, femme activist and writer Joan Nestle lovingly remembered touching and engaging in oral sex with a close friend during junior high sleepovers.

At the same time, feminine girls were invisible to young people who might have helped them connect to queer peer culture (when and where it existed) and often doubted the validity of their own desires. A white narrator named Jessica, for example, noted that it took her longer to come out as a lesbian because “I didn’t identify with what or who a lesbian was because of how I looked.” She responded to a question from Roey Thorpe about her adolescent years in the mid-1960s:

I knew two teenagers when I was growing up and they were very, very butch, and the word was that they were lesbians. And people would tease them and stuff, and I remember that I was somewhat intrigued by them, because they were women who loved women, but I also couldn’t understand it…. I didn’t have that same air about me or outward appearance, and I was also afraid of them, to be identified or associated with them. So it was in the back of my mind, the feelings were there.

Young Jessica’s association of lesbianism with female masculinity left her confused about the significance of her own attractions. Cross-sex attractions could work similarly to (and oven converged with) femininity to muddy the waters of queer self-identification. A Jewish woman born in 1948 told her interviewer, Ellen Lewin, that she wasn’t prepared to “transpose” her longing for a high school friend “into sexual language” because she was also “very sexually involved with boys.” And when she sought information on homosexuality, she added, the books only talked about men. As a normatively gendered girl who enjoyed sex with boys, she had few resources for making sense of her desire for another girl.

Feminine girls in the mid-twentieth century were less likely than their more masculine counterparts to be identified, surveilled, and targeted by others and may therefore have experienced a more prolonged period of uncertainty about their sexuality. Feminine bisexuality could entrench that uncertainty, which could produce internal conflict while simultaneously enabling a wider range of life paths (including motherhood) during an era of intense sexism and homophobia.

This research has methodological implications for historians of sexuality. Lesbian subcultures and mainstream gay and lesbian politics have devalued both femininity and bisexuality in ways that have shaped the archival and oral historical record. Scholars who rely heavily on oral history interviews, in particular, must be aware that narrative structures that consolidate lesbian identity development often obscure accounts of femininity and bisexuality. It is common, for instance, for narrators invested in constructing a coherent account of emergent lesbianism to dismiss the significance of cross-sex encounters and/or to emphasize the significance of same-sex intimate friendships in adolescence. By structuring an interview around the “coming out story,” which implicitly values visible and definitive forms of identification, interviewers and narrators sometimes reduce the complexity of gendered and sexual practices that occurred both before and after the privileged moment of “coming out.” Queer oral historians like Nan Boyd have discussed interview techniques that encourage narrators to disrupt dominant (even heteronormative) developmental narratives in favor of more open, critical, and fluid testimonies, but there is a great deal more work to be done in this area. Understanding lesbian history more expansively—including analysis not only of persistent same-sex desire as expressed through female masculinity but also bisexuality, queer femininities, changing gender and sexual configurations over the life span, and ephemeral or situational same-sex desire and behavior—will challenge us to write more complex histories that do justice to the range of gendered and sexual lives of queer women in the past and present.

Shannon Weber: My work on LGBTQ students at New England women’s colleges, and the hierarchies of popularity, desirability, and recognition based on race, class, and gender presentation, joins a growing conversation about queer femininities as intelligible and valuable in their own right. As femme fashion studies scholar Concettina Laalo notes, queer femininity “has been largely ignored by academics and distrusted in queer communities.” According to Laalo, the masculine imperative found within queer Assigned Female at Birth (AFAB)-centric spaces has acted as a form of homonormativity, in which “[t]he body and dress of the butch are analysed as communicative symbols of lesbianism and/or queerness, while heteronormative and homo-normative cultures deem the femme’s body and dress heteronormative and pushed aside, unanalysed and invalid.” These observations are certainly true for many of the queer femme-identified and/or femme-presenting interviewees in my project, as white, class-privileged masculinity continues to represent the visible and authentic face of queerness in AFAB-centric queer spaces.

From 2011 to 2014, I conducted 54 semi-structured interviews with LGBTQ students and recent alumnae/i of two women’s colleges in western Massachusetts. Out of these interviews, my queer femme interviewees reported their experiences on campus as a paradox. They praised their campuses as crucial sites of empowerment and safety in exploring their sexual identities, but they also described experiencing alienation, exclusion, and mistrust based on their departure from a white masculine aesthetic. As my interviewee Chloe, a white, feminine queer student who dated a more masculine and well-known female athlete on campus, explained to me, “Somebody on the rugby team said [to Chloe’s girlfriend], ‘Hey, who is that straight girl you’re trying to get in the bed?’ … And like, I had very long hair then; I guess length really is threatening to people.” Another interviewee, Jessica, a mixed-race queer femme student, explained to me, “[W]hen you think of, if you identify as a lesbian, however you think of the word ‘lesbian’ and you don’t picture yourself, why is that? … Or queer or bisexual or anything. Like, if you picture somebody else, why is that? Um, and a lot of that has to do with race. For me, at least. So, I want to do some sort of thing to be like ‘There’s more than one way to look queer. There’s more than one way to look lesbian or bisexual or whatever.’ And we have to address that.”

Due to the ways women’s voices, but especially the voices of women who are queer, trans, and/or of color, have so often been erased or heavily pathologized in the archive, the opening up of what “counts” as queer to queer people themselves is crucial in changing our understanding of the history of sexuality. The early medical studies that defined and diagnosed LGBTQ people in the late-nineteenth and early- to mid-twentieth centuries, especially in their tendency to link same-sex sexuality with gender variance, have unfortunately continued to inform contemporary assumptions about queerness. My interviewees represent a new twenty-first century archive to set the record straight—or more appropriately, queer.

Alix Genter an independent scholar with a Ph.D. in U.S. women’s and gender history from Rutgers University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, Risking Everything for That Touch: Lesbian Culture from World War II to Women’s Liberation, which expands understandings of butch-femme culture and identities in the midcentury U.S. Her article on butch-femme fashion and queer legibility is in the current issue of Feminist Studies. She has taught History and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers and The College of New Jersey.

an independent scholar with a Ph.D. in U.S. women’s and gender history from Rutgers University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, Risking Everything for That Touch: Lesbian Culture from World War II to Women’s Liberation, which expands understandings of butch-femme culture and identities in the midcentury U.S. Her article on butch-femme fashion and queer legibility is in the current issue of Feminist Studies. She has taught History and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers and The College of New Jersey.

Anastasia Jones earned her Ph.D. in History from Yale University. She is currently teaching in the Department of U.S. Studies at the University of Toronto. Anastasia is also working on a book project, The Standard Deviants: Female Intimacy and Homosexuality in Modern U.S. Popular Culture, which traces popular conceptions of intimacy between women in U.S. interwar culture. Anastasia is a recipient of the John Money Fellowship for Scholars of Sexology at the Kinsey Institute. And she will have an article, “She Wolves: Feminine Sapphists and Liminal Sociosexual Categories in the US Urban Entertainment Industry, 1920–1940” published in the May (2017) issue of the Journal of the History of Sexuality.

earned her Ph.D. in History from Yale University. She is currently teaching in the Department of U.S. Studies at the University of Toronto. Anastasia is also working on a book project, The Standard Deviants: Female Intimacy and Homosexuality in Modern U.S. Popular Culture, which traces popular conceptions of intimacy between women in U.S. interwar culture. Anastasia is a recipient of the John Money Fellowship for Scholars of Sexology at the Kinsey Institute. And she will have an article, “She Wolves: Feminine Sapphists and Liminal Sociosexual Categories in the US Urban Entertainment Industry, 1920–1940” published in the May (2017) issue of the Journal of the History of Sexuality.

Amanda Littauer earned her Ph.D. from Berkeley and is an Associate Professor of History and the Center for the Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Northern Illinois University. Her research focuses on 20th-century sexual culture, the history of women and girls in the modern U.S., and LGBT history. Her first book, Bad Girls: Young Women, Sex, and Rebellion before the Sixties, was published by University of North Carolina Press in 2015. She has published in sources such as The Journal of the History of Sexuality, The Journal of Women’s History, Queer Fifties: Rethinking Gender and Sexuality in the Postwar Years (ed. Heike Bauer and Matt Cook), and the forthcoming Routledge History of Queer America (ed. Don Romesburg). She is also co-chair of the Committee on LGBT History.

earned her Ph.D. from Berkeley and is an Associate Professor of History and the Center for the Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Northern Illinois University. Her research focuses on 20th-century sexual culture, the history of women and girls in the modern U.S., and LGBT history. Her first book, Bad Girls: Young Women, Sex, and Rebellion before the Sixties, was published by University of North Carolina Press in 2015. She has published in sources such as The Journal of the History of Sexuality, The Journal of Women’s History, Queer Fifties: Rethinking Gender and Sexuality in the Postwar Years (ed. Heike Bauer and Matt Cook), and the forthcoming Routledge History of Queer America (ed. Don Romesburg). She is also co-chair of the Committee on LGBT History.

Shannon Weber teaches in the Women’s and Gender Studies department at Wellesley College. She holds a Ph.D in Feminist Studies from the University of California and has published research in venues such as Sexualities, Journal of Homosexuality, and Journal of Lesbian Studies. Dr. Weber is in the process of writing a book manuscript, Queerer Than Thou: LGBTQ Youth Cultures at U.S. Women’s Colleges and the Politics of Exclusion, based on her dissertation research. Her commitment to furthering femme visibility through style has recently been featured in a piece as part of the Hi Femme! project at DapperQ. She lives in Boston, Massachusetts and enjoys exploring New England with her partner and dog.

teaches in the Women’s and Gender Studies department at Wellesley College. She holds a Ph.D in Feminist Studies from the University of California and has published research in venues such as Sexualities, Journal of Homosexuality, and Journal of Lesbian Studies. Dr. Weber is in the process of writing a book manuscript, Queerer Than Thou: LGBTQ Youth Cultures at U.S. Women’s Colleges and the Politics of Exclusion, based on her dissertation research. Her commitment to furthering femme visibility through style has recently been featured in a piece as part of the Hi Femme! project at DapperQ. She lives in Boston, Massachusetts and enjoys exploring New England with her partner and dog.

Cookie Woolner is a cultural historian of race, gender, and sexuality in the modern U.S. She is an Assistant Professor in the History department at the University of Memphis and received her PhD in 2014 from the University of Michigan in History and Women’s Studies. Her current manuscript, “The Famous Lady Lovers:” African American Women and Same-Sex Desire Before Stonewall, is the first in-depth examination of black women who loved women in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in the U.S. Her article, “‘Woman Slain in Queer Love Brawl:’ African American Women, Same-Sex Desire, and Violence in the 1920s Urban North,” was recently published in a special issue of The Journal of African American History. She is on the governing board of the Committee on LGBT History.

is a cultural historian of race, gender, and sexuality in the modern U.S. She is an Assistant Professor in the History department at the University of Memphis and received her PhD in 2014 from the University of Michigan in History and Women’s Studies. Her current manuscript, “The Famous Lady Lovers:” African American Women and Same-Sex Desire Before Stonewall, is the first in-depth examination of black women who loved women in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in the U.S. Her article, “‘Woman Slain in Queer Love Brawl:’ African American Women, Same-Sex Desire, and Violence in the 1920s Urban North,” was recently published in a special issue of The Journal of African American History. She is on the governing board of the Committee on LGBT History.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

You hit the nail on the head in the very beginning, pointing out that most research on women who love women has been done by white males. So much still needs to be done to overcome the stereotypes that are still so rampant in society. It is time people stopped saying things like, “But she appeared so normal!”