Moderated by Carolyn Bronstein and Whitney Strub

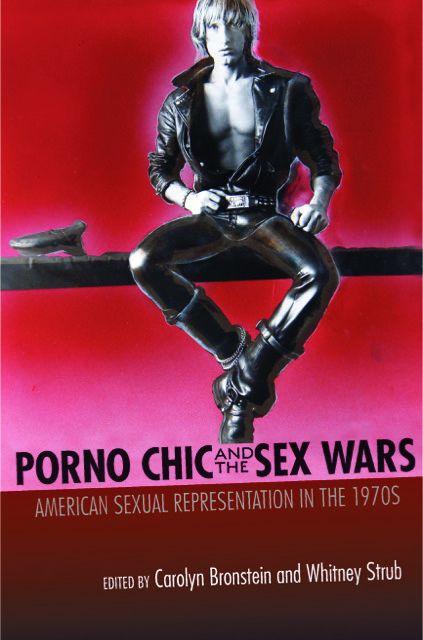

In our new coedited volume, Porno Chic and the Sex Wars: American Sexual Representation in the 1970s, we look back at a distinctive moment in American history when pornography was consumed openly, by diverse audiences, and with far less public shame than today. It also featured more authentic sex, at least in terms of the kinds of natural bodies that prevailed in that pre-silicone/Viagra era.

For many Americans, the emergence of the “porno chic” culture of the 1970s provided an opportunity to embrace the sexual revolution and participate by attending films like Deep Throat (1972), and reading leading magazines like Playboy, which enjoyed its highest circulation numbers in the early 1970s. Pornographers looked beyond the mainstream heterosexual audience (which current films like Fifty Shades Darker and HBO’s upcoming series The Deuce privilege) to create a new, vibrant gay porn genre and female impersonator magazines that provided erotic content for trans people.

The lesbian SM community flourished, especially on the west coast, and conservative evangelical Christian authors penned salacious marriage manuals that brought pornography squarely into the revered marital bed. Bob Guccione founded a porn magazine for women, arguing that female readers deserved as thrilling an erotic experience as the men, who read Penthouse, enjoyed. Porn played with race in multiple ways, from the tacit eroticization of whiteness in Marilyn Chambers’ girl-next-door performing sex acts on-screen, to the intersecting body of Johnnie Keyes who paired with her in an exoticized performance of “African” blackness. We can read this as a clear affirmation of white supremacist erotics or we can read it against the grain, as Jennifer Nash does in her book, The Black Body in Ecstasy.

As the 1970s recede in public memory, something dire is happening to that decade’s sexual cultural products. The actual films are fading into oblivion, as victims of a chemical breakdown process that destroys images captured on celluloid film stock, and the magazines and other erotic ephemera are increasingly hidden away in archives, out of public view. As the contributors to this roundtable (and to the Porno Chic collection) discuss, this is a pivotal moment to document what 1970s pornography meant to its producers and consumers.

Why is it important to study pornography of this era (say, the 1970s broadly speaking), and further, how does one go about researching and writing the history of something so poorly archived?

Gillian Frank: My research explores how conservatives responded to the “pornography revolution” of the 1970s. With the growth of a multi-billion dollar sex industry—which included magazines, films, mail-order services, bookstores, and phone sex lines—came growing worries among religious conservatives about the prevalence of explicit sexual representations. Groups such as Anita Bryant’s organization Protect America’s Children (formerly Save Our Children), Jerry Falwell’s the Moral Majority and Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum, identified pornography as a source of danger to families and children.

In other words, the 1970s saw a veritable explosion of pornography and a coinciding eruption of conservative concern about pornography. Studying concerns about pornography can tell us a great deal about the deep connections between culture and politics during that decade. Embedded in conservative anti-porn activism was an attempt to organize gender roles and sexual norms. Conservatives sought to offer clear and limited answers to questions such as: Where and when should sex take place? Who should be allowed to have sex (and with whom)? Which sex acts are permissible and impermissible? What roles and positions should men and women assume during sexual activities? What is the purpose of sex? And who should educate young people and a broader public about sexual values?

Notably, not all conservatives opposed sexual experimentation or variety. However, they did seek to channel such activities into marriage. Pornography (both filmic and written), on the other hand, threatened conservatives because it incited solitary pleasures, encouraged experimentation, offered limitless and sometimes anatomically improbable sexual options, and showcased gender variance. Visually, narratively, and through its uncontrolled circulation, pornography undermined many of the sexual norms conservatives sought to preserve: monogamous heterosexuality and the prerogative of parents to educate their children about sexual norms.

In researching the histories of conservatism and pornography, I learned that conservative archival collections are shot through with pornography. Conservative opponents of pornography obsessively reproduced the very material they so adamantly disavowed. In their letters to politicians, their submissions to government commissions “studying” obscenity, in internal correspondence, in treatises about the subject, and in their fundraising appeals, conservatives literally exhibited pornographic images. Those seeking to recover pornographic texts and culture can find their residue all over the conservative movement of the 1970s.

All of which is to say that the histories of conservatism and pornography are not necessarily oppositional but co-constituted. My own work in this edited volume shows how even as religious conservatives spoke out against pornographic films, they incorporated many elements of pornographic literature into their advice literature, which encouraged women and men to have increased sexual activity and greater sexual variety within the context of marriage.

Jennifer C. Nash: If pornography is a window into collective fantasy, and race is America’s preeminent sexual fantasy, then pornography is a rich repository of information about racial fictions, fantasies, projections, desires, and longings. For me, pornography is an explicit window into how ideas of racial difference are sexually constructed. Race structures pornography—fictions of abundant black sexual appetites and, at times, black sexual undesirability. With its incessant promises of making visible racial difference and its inability to ever make good on those promises, pornography alerts us—again and again—to how racial desires permeate American life.

The so-called Golden Age of pornography, the 1970s, is a particularly ripe place for thinking about pornography’s traffic in fantasies of racial difference because it was the moment when black bodies were ushered on-screen after their relative absence from earlier eras of adult film history. Desiree West, the subject of my chapter, and Johnnie Keyes, for example, became pornographic stars whose presence on-screen enabled the depiction and circulation of previously unrepresented desires. My own work does not treat their presence as evidence of the inherent racism of the pornography industry and instead asks about the panoply of pleasures (erotic, sexual, aesthetic, political) the presence of black bodies on-screen made possible for pornographic performers (and spectators) on all sides of the proverbial color-line. I show how pornographic spectators were educated on how to desire black female flesh through Desiree West. Importantly, the 1970s was also the moment when black spectators were imagined as pornographic voyeurs and where pornographic marketplaces began to craft films around imagined black pleasures, which included the sexual, but also the aesthetic, the sonic, and the political, revealing that pornography’s pleasures are myriad and complex.

The question of the archive is at the center of my chapter on Desiree West. Of course, as “porn studies” has become more institutionalized—more books, more articles, and even a scholarly journal devoted to understanding pornographies—there are more pornographic archives that look like conventional ones. Yet for those of us interested in producing scholarship on pornography, the archive often feels haphazard. My chapter in this volume is an attempt to think through the question of the archive qualitatively–what happens when researchers interview those who labored in the industry and attempt to construct porn histories around their memories? As I argue in my chapter, memory, too, is haphazard. Thus, part of the experience of being a porn scholar is working with unconventional and incomplete archives that are shifting and evolving.

Joe Rubin: The landscape of American-made sex films during the 1970s was a microcosm of some of the most diverse pockets of filmmaking in the US, during an already exceptionally transgressive era for the cinematic arts. The makers of sex films, much more so than their Hollywood counterparts (and even many other types of genre filmmaking), traversed all variations of race, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic background and, most importantly, levels of artistic training and experience, rendering many of the resulting works, even those directed by visionary auteurs and starring talented actors, as outsider art.

As a film archivist who has focused primarily on preserving hard and softcore features, I’m faced with the perpetual challenge of both charting and prioritizing a type of cinema, which was minimally documented upon its creation and has, in the decades since, become among the least cared for of all film ‘genres.’

Guesswork and conjecture are inevitable and the limited availability of reliable primary sources (especially when researching directors and actors, many of whom worked pseudonymously) makes assuring the accuracy of information gathered all the more difficult. As my work primarily involves the handling and maintenance of physical film elements, an extensive knowledge of the photographic and lab techniques used at the time is paramount to ensuring that each film I help preserve is done so with the greatest adherence to the assumed intended visual presentation of its creator.

While many large and prestigious archives house collections of feature length sex films, in quantities varying from a handful of titles to, in some cases, hundreds of unique works, the attention paid by such institutions to even properly and accurately cataloging their holdings, let alone going beyond taking the most basic steps to ensure their long-term preservation is, by and large, minimal. Most such archives go even further, downplaying or flat out denying the titles in their care to anyone other than carefully selected scholars, thus further burdening both the researcher who wishes to access rare films for study, as well as the preservationist who wishes to maintain and help curate the most significant and endangered works, so as to ensure their survival into the future.

The picture I paint is intentionally bleak. For any scholar, researcher, or even casual viewer who may be overjoyed at the re-release or restoration of a long sought after film, there will always inevitably be countless others decaying away in forgotten or inaccessible vaults, or destroyed altogether. For the world of academics and film preservationists to truly make an impact, we must collectively do whatever is in our power to ensure that the most valuable of primary sources—the work itself—is preserved and made available to all who seek it.

Carolyn Bronstein is the Vincent de Paul Professor of Media Studies in the College of Communication at DePaul University, and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of History and the American Studies Program. She is the author of Battling Pornography: The American Feminist Anti-Pornography Movement, 1976-1986 (Cambridge, 2011) and coeditor with Whitney Strub of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars: American Sexual Representation in the 1970s (University of Massachusetts, 2016).

Gillian Frank is a Managing Editor of NOTCHES: (re)marks on the History of Sexuality. He is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. Frank’s research, which has appeared in journals such as Gender and History, Journal of the History of Sexuality and Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and Reproductive Politics in the United States Before Roe v Wade. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

Gillian Frank is a Managing Editor of NOTCHES: (re)marks on the History of Sexuality. He is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. Frank’s research, which has appeared in journals such as Gender and History, Journal of the History of Sexuality and Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and Reproductive Politics in the United States Before Roe v Wade. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

Jennifer C. Nash is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (Duke University Press, 2014), which was awarded the Alan Bray Prize by the GL/Q Caucus of the Modern Language Association. She is also the editor of Gender: Love (Macmillan). She has published articles in journals including GLQ, Social Text, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Review.

Jennifer C. Nash is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (Duke University Press, 2014), which was awarded the Alan Bray Prize by the GL/Q Caucus of the Modern Language Association. She is also the editor of Gender: Love (Macmillan). She has published articles in journals including GLQ, Social Text, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Review.

Joe Rubin is an American film archivist and co-founder of the acclaimed home video company, Vinegar Syndrome. His work to restore and preserve American hardcore feature films has been featured in The New York Times, Playboy, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

Joe Rubin is an American film archivist and co-founder of the acclaimed home video company, Vinegar Syndrome. His work to restore and preserve American hardcore feature films has been featured in The New York Times, Playboy, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark, where he co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011), and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark, where he co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011), and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

One Comment