In 1896, a woman university student living in Zurich published in pamphlet form an extraordinary tirade against the sexual culture of men in her society. The author was Johanna Elberskirchen, and the title was (roughly) “Men’s Prostitution.” It was intended, she proclaimed, to present her “unconditionally subjective” perspective on sexual morality. According to her, men and their moral code were the authors of “immorality, bestiality,” and corruption in sexual life. Sexually, men were “vermin and swine” who “attack woman, make her life bitter, poisoned, miserable” with their “whole wretchedness,” their “cowardice,” “hypocrisy,” “weakness,” and “ghastly, loathsome abuse of women.” Men, she raged, had turned the whole world into a “brothel, rotten and corrupt and diseased . . . from top to bottom!” Elberskirchen concluded her pamphlet with a vow: “Yes, I am a woman. Yes, I know nothing of your affairs, your needs. Yes, I should shut up. Yes, yes, yes—a brilliant response . . . But I won’t shut up. And you will lynch me. But I won’t shut up.”

Nor did she. This pamphlet was the first in a series of publications before World War I in which Elberskirchen established herself as a controversial voice in the rapidly expanding public debate about sexuality, sexual morality, decency, and gender relations. Elberskirchen was undoubtedly an extreme case, on the radical “fringe.” And yet, her rhetorical position as it evolved over the next decade was broadly shared among critics of prevailing sexual mores.

Elberskirchen claimed her right to represent her own “subjective” moral position, but she also appealed to the authority of biological science in legitimating that position. In a second set of pamphlets published between 1903 and 1905, Elberskirchen not only expressed her moral outrage, but also laid out important scientific claims. “Revolution and Deliverance of Woman” (1904) denounced the “bestiality, animalism” created by men’s social, economic, and sexual privilege, their ability to indulge in a hypertrophied, perverted, “wild, senseless, mindless sexual life” at the expense of women, whose legal and social rights (for example, their access to education or the professions) and financial opportunities were profoundly circumscribed, and who were therefore extremely vulnerable to sexual predatory men. Rejecting commonplace assertions of the radical sexual difference between men and women, she held that the fundamental “bisexual character” of humanity was a “biological fact.” What was more, the natural state of relations between the sexes was obviously and necessarily not hostility and radical separation but “connection,” sexual union. And finally, she held that women were obviously biologically superior to men because they were “the source of life” and hence the “axis of the family, society, and culture.” The tyranny of men, therefore, was unnatural and artificial; the natural state of humanity was matriarchy. Men’s social privilege and sexual culture were not only immoral, then, they were also biologically pathological.

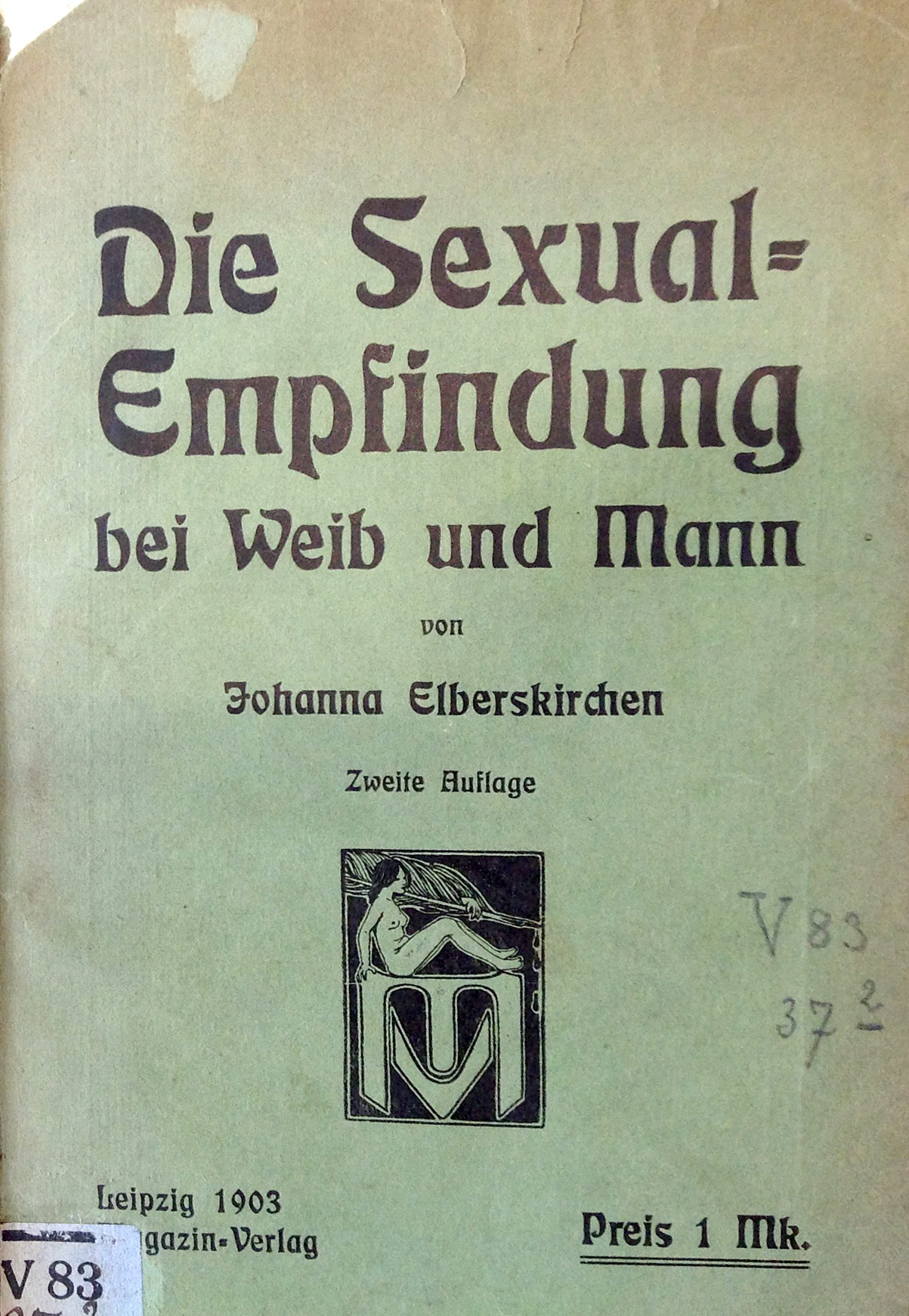

Elberskirchen further argued that women’s sexual freedom and social equality were biologically natural, and the right to freedom of sexual choice was rooted in the facts of human biology. In “Sexual Feeling in Man and Woman” (1903), she maintained that the common assertion that women’s sex-drive was different from that of men “has no factual or scientific foundation.” In both men and women, “body and soul, the whole human being is subject to the same powerful feeling and drive, a single desire.” Sexual privilege had merely created a “pathological condition” in men, a hyperactive and “hysterical” sexual “over-excitation.”

Elberskirchen advocated instead a normal, healthy, natural degree and gratification of sexual desire for both men and women, since “from God comes all nature. Our sexual drive and our sexuality too . . . It is of God, not the devil . . . Let’s say Yes to our sexual desire, a joyful, happy, holy Yes. God is within us. In us and in our pleasure. Let’s be gods!” In “Love Among the Third Sex” (1904), Elberskirchen reached even more radical conclusions. Embryological facts proved, she held here, that “in the final analysis we are all homosexuals . . . More precisely: we are all bisexual” in the biological sense and, she presumed, also in our sexual capacities. More than that, homosexuality was clearly superior to heterosexuality, both because heterosexual desire had “brought enormous suffering upon humanity, particularly upon woman,” and because homosexual love was love between two people who could truly understand each other, it was “soul-love . . . , spiritual love . . . fine and beautiful and natural.”

Finally, in “Sexual Life and Sexual Abstinence in Women” (1905), Elberskirchen even posited a “natural right to an active sex life,” a right for women to “full freedom of sexual choice” and the right to “form a biological marriage”—that is, monogamous non-marital sexual and reproductive relationships. Only such freedom could guarantee the health and improvement of the species by ensuring that women were not dominated and victimized by morally degenerate men (many of them suffering from venereal diseases, for which there were at the time no effective therapies).

Elberskirchen sounds to us today like an extraordinary voice, championing extraordinary views. Yet what is striking about her is that in many ways she was rather ordinary. One of the more remarkable aspects of this period is its proliferation of sexual subject-positions so that she was hardly alone in asserting her right to her own voice.

Gisela von Streitberg had argued already in 1891 that women should rely on observation of their “own nature” in trying to understand what made sense for them sexually, rather than trusting the medical literature, which—given that women in Germany were barred from taking medical degrees and indeed (at the time) from any university study—was “authored mostly by and for men and read by them.” Elberskirchen’s views on male sexuality were also not that far from those advanced by the conservative Christian morality movements since the 1880s. As Der Volkswart, the journal of the national Catholic morality movement, put it in 1913, “in thousands and thousands of cases it is the men who seduce women and girls, abuse them, buy and sell them, rape and assault them.” Radical women agreed. The leading sex reformer Helene Stöcker held that “in sexual matters the average man is still not a civilized person, but a crude barbarian.” And Elberskirchen’s affirmation of female sexuality, while scandalous to conservative Christians, was common among radical women. Ida Boy-Ed, a prolific author of women’s novels, demanded, for example, in 1911 the development of a healthy and natural understanding of female sexuality, and suggested that parents and teachers should “awaken in woman the courage to be sensual!” Nor was the religious tone of her appreciation of sexuality unusual; the influential Swedish philosopher Ellen Key argued in 1898, for example, that “when the power of motherhood appears on earth in its full glory, then it . . . will give birth to the salvation of the world.” Others, enamored of Darwinism and what they saw as its social implications, referred to their faith in evolution driven by strong, independent women’s role in sexual selection as the “religion of love,” the “religion of life,” or the “religion of joy.”

Elberskirchen’s conceptualization of homosexuality made her more unusual. Yet one early survey from 1914 (admittedly with a very small sample size, and including almost exclusively educated middle-class respondents) suggested that almost one in ten women and one in twelve men identified as homosexual or bisexual. In some larger cities, particularly Berlin and Munich, there were quite lively and well-organized homosexual social milieus. And here again, Elberskirchen’s views were not completely unique. An example is a 1905 article in Germany’s first sex-reform journal, Geschlecht und Gesellschaft, which argued that lesbians had “a much deeper, more spiritualized love” than the average heterosexual, “a necessary consequence” of the fact that in lesbian relationships two “womanly creatures”—much more capable of love than animalistic men—loved each other.

Some male homosexuals made similar arguments; Benedict Friedlaender, for example, argued that love between men was the glue of social and political order, while heterosexual desire was merely reproductive, egoistic, and animalistic. And the argument that all people were bisexual was a central theme in the thinking of male homosexual rights advocates, such as Friedlaender or Magnus Hirschfeld.

In short, radical discourse on sexuality in this period was characterized by precisely the mix of themes central to Elberskirchen’s thinking: moral outrage, a fierce commitment to individual rights, and faith in the power of scientific objectivity to erode convention and the privileges it sanctioned. Elberskrichen simply spelled out the implications of combining this triad with particularly uncompromising clarity. She was, then, a woman of remarkable and admirable intellect and courage. But she was not exceptional—and this is what makes her interesting. She was very much a woman of her time.

Edward Ross Dickinson took his BA and PhD from the University of California, then taught for eight years at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand and six years at the University of Cincinnati before returning to the University of California. He is currently a Professor of History at UC Davis. He has published on child welfare policy, alpinism, empires, sexuality, morality movements, vocational education, crime, racism, feminism, modern dance, and reform movements in Germany.

Edward Ross Dickinson took his BA and PhD from the University of California, then taught for eight years at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand and six years at the University of Cincinnati before returning to the University of California. He is currently a Professor of History at UC Davis. He has published on child welfare policy, alpinism, empires, sexuality, morality movements, vocational education, crime, racism, feminism, modern dance, and reform movements in Germany.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com