The onset of the AIDS epidemic in the United States coincided with the rise of Ronald Reagan, who won the presidency in 1980 in part by promising to roll back the welfare state and return the country to a time of simpler moral values. Those most affected by AIDS, particularly gay men and poor people of color, were frequent targets of the new administration and its allies. Policymakers and pundits who wanted to shrink the welfare state linked social programs to sexual and racial minorities, who they portrayed as social deviants undeserving of public support.

Federal agencies offered some support for the fight against AIDS in communities of color during the 1980s. But black gay men, marginalized by both race and sexuality, were doubly disadvantaged in claiming public resources for the fight against AIDS. Although black gay men were among those most affected by AIDS, in 1988 when the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) rolled out a new grants program for minority groups fighting the disease, they included only one gay-identified organization in the first round of 32 recipients. That group, the National Association of Black and White Men Together, used this grant money to launch the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention (NTFAP), an AIDS education program for gay men of color.

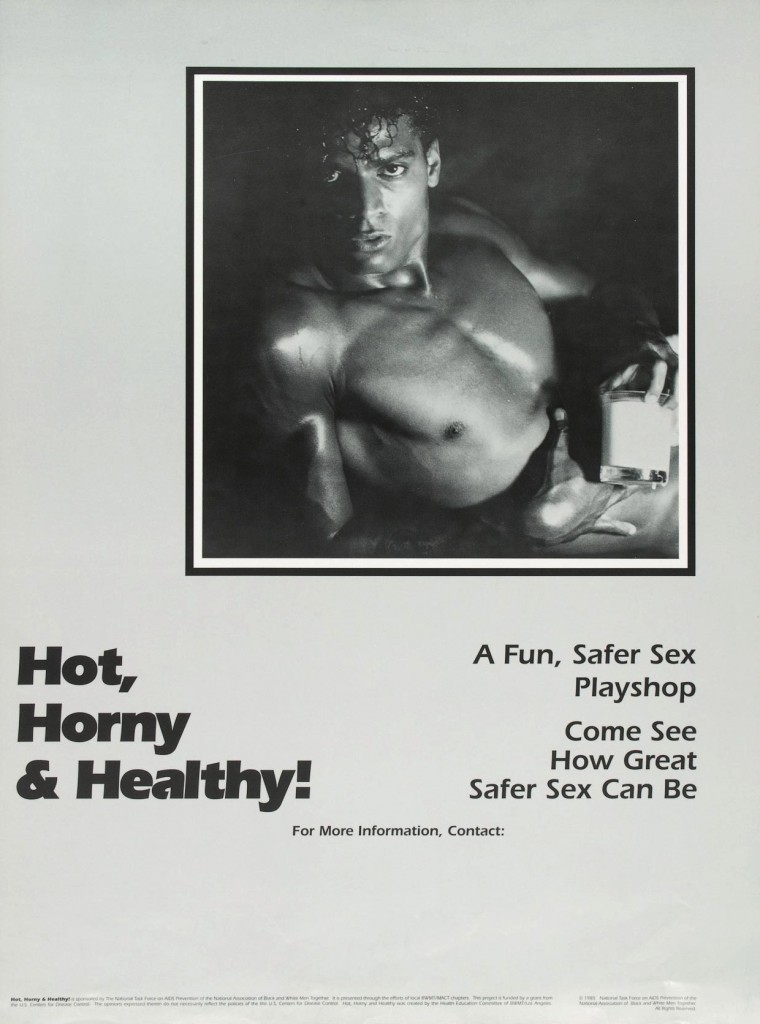

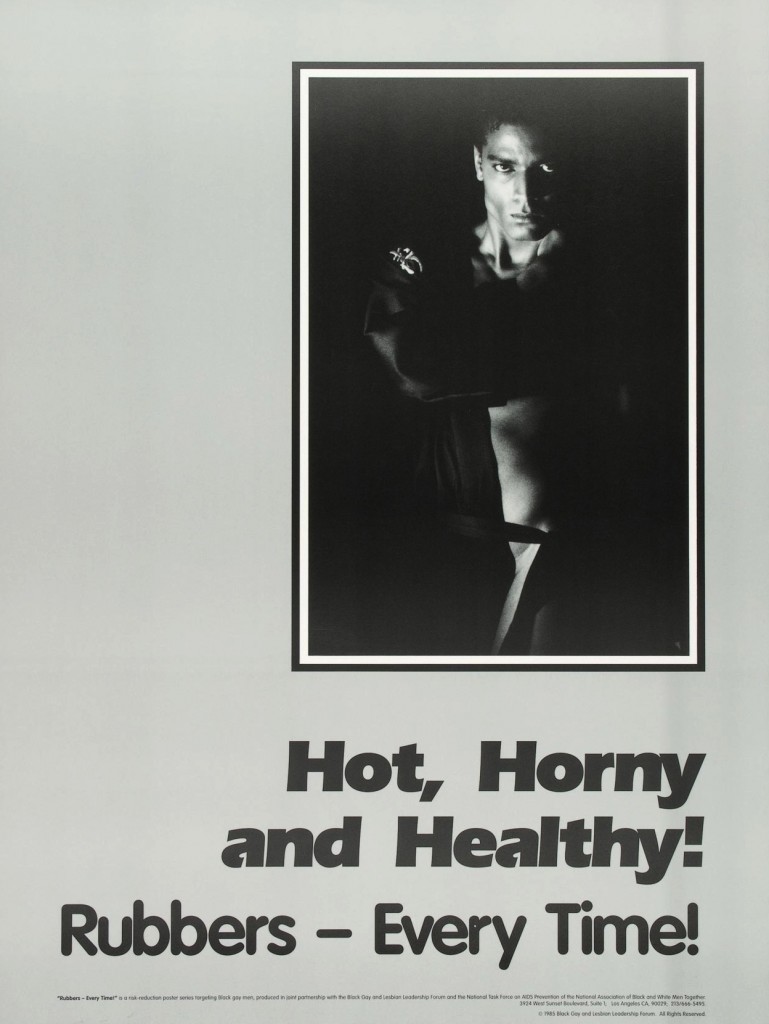

NTFAP staff and volunteers offered programs such as Hot, Horny & Healthy!, a “playshop” designed to show participants that safer sex could help stop the spread of HIV and still be pleasurable. The playshop featured roleplaying exercises, in which participants practiced negotiating safer sex with their partners, and “condom races,” in which team competed to see who could put on and remove a condom from a dildo the fastest.

National Task Force on AIDS Prevention’s sex-positive approach to AIDS education drew fire from social conservatives. As in other skirmishes in the “culture wars,” they objected to the use of public funds to promote any form of sexuality that took place outside of monogamous heterosexual marriage. However, opponents also attacked the program in coded racial terms, suggesting that NTFAP should be defunded not only because it served gay men, but because it served black gay men. As the battle over Hot, Horny & Healthy! makes clear, both race and sexuality figured into debates at the height of the AIDS crisis over who deserved state assistance, and who did not.

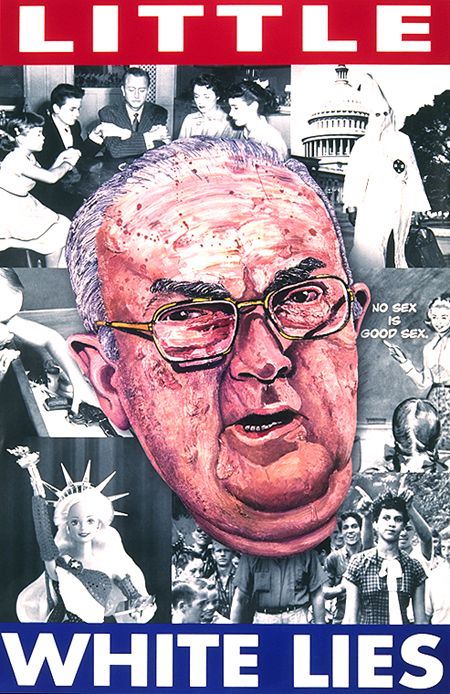

Such debates took place within the Reagan administration, where conservative cabinet officials pushed for a response to AIDS that stressed monogamous sex within heterosexual marriage, and opposed AIDS education messages that targeted gay men or promoted condom use. At the same time, North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms succeeded in passing legislation that prohibited the use of federal funds by the Centers for Disease Control to “promote, encourage, and condone homosexual sexual activities or the intravenous use of illegal drugs.” At least for a few years, Helms’ legislative actions largely succeeded in keeping federal funding away from AIDS education programs targeted to those most at risk. Moreover, any group who did receive federal support had to fight, in the words of NTFAP Executive Director Reggie Williams, “with one Helms Amendment-tied hand behind its back.”

Controversy over the use of federal funds for Hot, Horny & Healthy! erupted after syndicated columnist Cal Thomas attacked NTFAP in newspapers nationwide. In a column entitled “Taxes Pay for ‘Horny & Hot’ Workshops,” and published in early November of 1990, Thomas lamented that in “tight budgetary times” the CDC had “found enough of our tax dollars to underwrite a program for a homosexual group called Black and White Men Together.” Thomas homed in on the playshop’s condom races, which he argued were both an affront “to common sense and common decency” and prohibited under Helms’ legislation.

Perhaps in a nod to black social conservatives, Thomas presented blackness and homosexuality as mutually exclusive. He argued that ‘Black and White Men Together’, as a “homosexual group,” had illegitimately applied for “an ethnic/racial minority grant”—never mind that NTFAP staff and volunteers were made up largely of black gay men. Here Thomas presented the CDC grant as part of an underhanded attempt by gay rights groups to pervert civil rights gains by “giv[ing] their sexual behavior the same kind of legal approval that minority groups have under anti-discrimination statutes.”

However, Thomas also appealed to readers’ nostalgia for a bygone America that was both sexually and racially conservative. He contrasted the NTFAP grant with the situation of “[p]oor old Lawrence Welk,” who “has been getting a lot of flak for the $500,000 appropriated by Congress to restore his boyhood home in North Dakota.” Welk’s TV variety show had run from 1955 to 1982, and evolved little beyond the decade in which it first aired. To be sure, the middlebrow entertainer had been a staple of American popular culture for decades. But by invoking Welk, Thomas suggested that commemorating his vision of America—one untouched by the tumultuous 1960s and 70s—would be a better use of taxpayer dollars than helping gay men protect themselves from HIV and AIDS.

When Reader’s Digest excerpted Thomas’ column almost a year later, in September 1991, editors presented Hot, Horny and Healthy! even more pointedly as a waste of taxpayer dollars. They ran the story as part of a feature called “THAT’S OUTRAGEOUS!” which carried the subtitle “Spotlighting absurdities in our society is the first step to eliminating them.” Here editors juxtaposed Thomas’ story with others, including one about a man who “made tanning booth appointments and honed his body in the gym” to prepare for the Mr. Massachusetts Male America Pageant, all while receiving worker’s compensation payments from the state of Massachusetts.

The magazine invited readers to laugh at the man’s queerness as a pageant contestant alongside the “absurdity” of the Hot, Horny & Healthy! condom races. Concurrently, the magazine positioned the news items as stories about the abuse of government largesse, which were embedded in a racially coded discourse used to justify deep cuts to public spending.

Ten years after Ronald Reagan ascended to the White House in part by attacking “welfare queens”, the idea that people of color preferred living well on the dole to an honest day’s work would have been firmly implanted in readers’ minds. By placing Thomas’ column alongside the Mr. Massachusetts story, Reader’s Digest invited readers to consider Hot, Horny and Healthy! an “outrageous” abuse of public funds—not only by gay men seeking “legal approval,” but specifically by black gay men.

NTFAP struck back at Cal Thomas and Reader’s Digest in a press release that asserted their credibility as AIDS educators. Whereas Thomas and Reader’s Digest played up racist stereotypes about black community groups as corrupt or lacking professionalism, the press release insisted that NTFAP’s programs were “professionally designed, repeatedly reviewed, and scrupulously evaluated.” Moreover, Reggie Williams, NTFAP’s Executive Director, insisted that AIDS programs for his constituents were a legitimate use of public funds, since “African American gay and bisexual men pay taxes too.” Nevertheless, Al Cunningham, who served as NTFAP’s Media Coordinator, recalls that the group lost its federal funding as a result of the controversy.

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, gay men and poor people of color alike suffered from government neglect. Those living at the intersection of those two groups—namely gay and bisexual black men, many of whom also lived in poverty—were among the hardest hit. Conservative pushback against public funding for AIDS education made it clear that those most at risk of HIV did not belong in the body politic, and the resulting lack of federal funding for AIDS programs consigned hundreds of thousands to early deaths. These included not only black gay men, but also drug users, sex workers, poor women of color, transgender women, and incarcerated people—all of them seen in one way or another as deserving neither sympathy nor public support, and all of them casualties of the culture wars.

Dan Royles is an assistant professor of history at Florida International University. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. He is also working on an oral history project and digital archive dealing with the history of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

Dan Royles is an assistant professor of history at Florida International University. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. He is also working on an oral history project and digital archive dealing with the history of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

IS THIS A MILESTONE FOR NOTCHES? Dan Royles’ excellent dispatch about the battle to put sexual and racial realities at the top of the AIDS prevention agenda is the first post on the blog that I’ve seen to begin with a warning and a series of options: “Be careful with this message. It contains content that’s typically used to steal personal information. Learn more Report this suspicious message Ignore, I trust this message.” I clicked “IGNORE” and felt once again the fears and fires of the battle for truthful useful AIDS education. The legacy of these fights endures as a warning during our own dangerous time. We should for sure “trust this message,” and pass it on. It needs to be told again and remembered always.

In the 1980s and 1990s (and still lingering today), there was a great deal of suspicion in the African American community of any government health recommendation because of the legacy of the Tuskegee experiment, and the black Christian church, traditionally a center of trusted information dispersal, was uncomfortable with homosexuality. These two factors also isolated gay African American men from information that might have taught them how to protect themselves.

Thank you for an excellent post.