Well poised, alert persons, not young. Frank on their sex: experienced in variety, scientific habits of mind. Gentle endearments during caresses, but not at high points. Dressed, a little deep kissing and seizures, before to bed to fulfil offer of demonstration of usual relations.

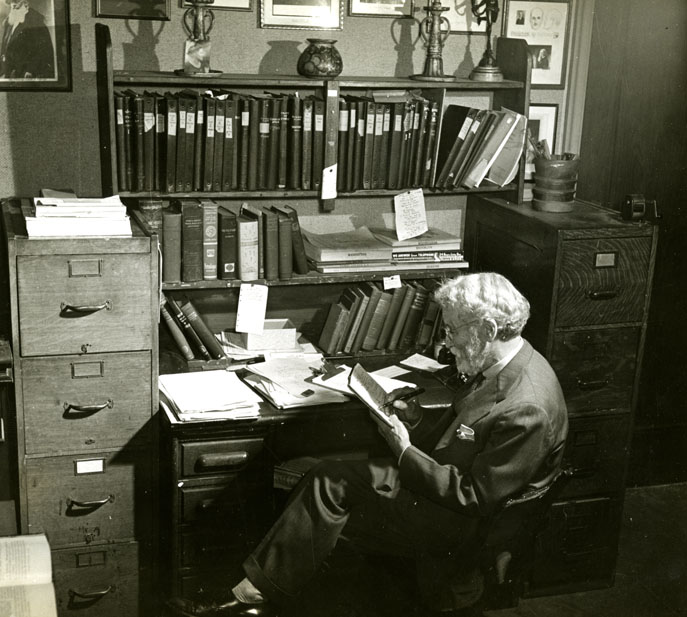

So begins the description of one of five live sexual encounters that the obstetrician/ gynecologist Robert Latou Dickinson (1861–1950) observed in 1945 and 1946. The participants in the encounter were there at the behest of the Indiana-based researcher Alfred C. Kinsey (1892–1956). In 1945 and 1946, Dickinson was in his mid-eighties, long retired from daily medical practice in Brooklyn, New York, but still an active scholar and artist. His numerous publications included A Thousand Marriages (1931), Control of Contraception (1931), Human Sex Anatomy (1933), and A Single Woman (1934), all of which drew on the data that he had gathered on women’s sexual lives from decades in the clinic. Kinsey was still best known in the scientific world for his expertise on the gall wasp, but he would soon become world famous for the publication of Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948). Dickinson’s textual and illustrative representations of these five encounters, which he gave the secondary title “Time and Tied,” show both the limitations of gathering sex research data from medical practice and the soon-to-be future possibilities of data gathering with live couples.

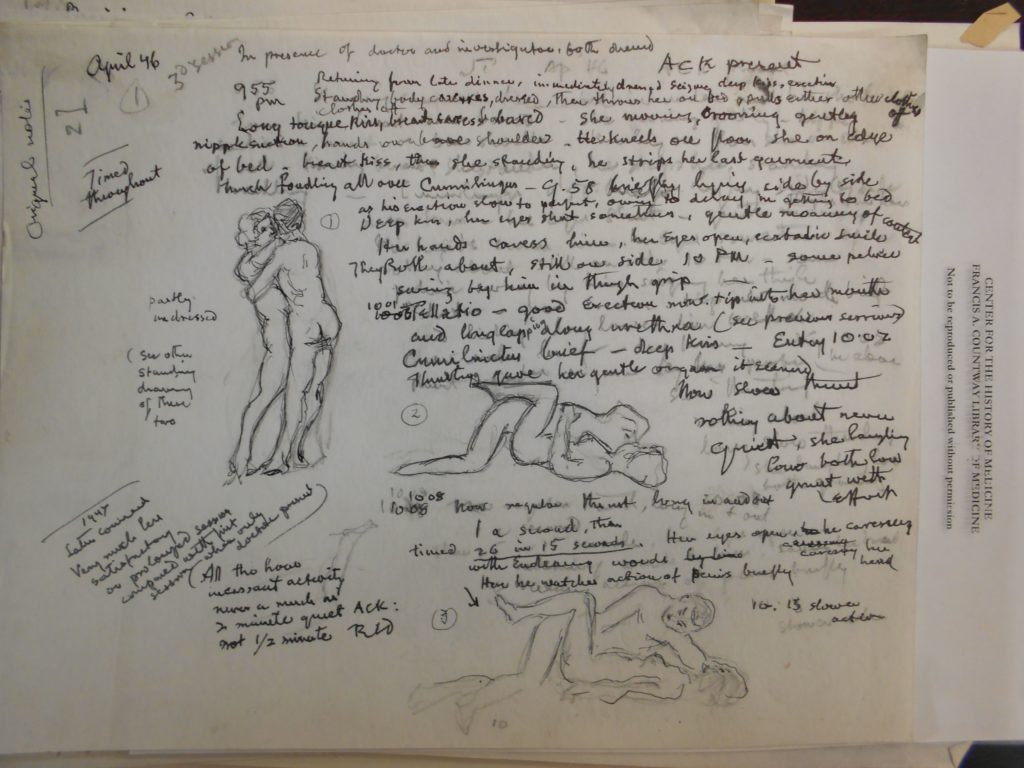

The ten pages of text and drawings, together with notations in Dickinson’s daily diary, provide the context of their creation. The same unnamed couple, whom he described as “highly regarded, students of marriage and sex relations,” participated in all five encounters. The first three took place with Dickinson alone in an unknown location in December 1945 and January 1946, and the last two occurred the first week of April 1946 with both Kinsey and Dickinson present. They were held at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia, where the two men were taking part in a meeting of the National Coalition of Family Relations. Dickinson wrote that both he and Kinsey stayed clothed during the sessions. He spoke only briefly with the couple beforehand, asking if he could view the woman’s vaginal wetness and levator ani (pelvic) muscle before they began, and if they could indicate when they were close to orgasm.

Dickinson was interested in recording two types of data: qualitative (narrating and drawing the couple’s movements) and quantitative (counting the number of penile thrusts and timing the couple’s orgasms). The texts read like a sports announcer narrating an athletic event play-by-play for an audience, which in a way it was. From the fourth encounter in April 1946:

10.01; fellatio, good erection, glans into her mouth, long tongue-stroking along urethra, as in previous sessions, cunnilingus brief, deep kiss, 10.02 entry. His thrusting gives her gentle orgasm almost at once, then slower thrusts at about one second intervals, she below, with never a minute’s quiet in rolling about, she laughing, both gently grunting with the muscular effort. 10.08, now long thrust, almost out, then deep inside, regular, vigorous, mostly once a second timed, but sometimes quicker, as 25 in 15 seconds. Caresses her head with love talk, briefly watches his penis in action as slower rhythm at 10.13. Her orgasm at 10.15, more vigor, about 20 seconds by her behavior. He came near to it, gasping, but then quit his gluteal activity and slowed, all this time he above.

This account of the couple’s movements illustrates Dickinson’s aim of capturing as much of the encounters’ qualitative and quantitative elements as he could. During the third encounter, he recorded that the total thrusting time in various positions was forty-six minutes. “Allowing for gaps while changing postures,” he noted, “we run from 2000 to 4000 thrusts in the three-quarter hour of steady activity.” It is not clear what, if anything, he intended to do with the information that he recorded, or if he and Kinsey had any conversation about the encounters afterward.

Dickinson’s descriptions of these encounters illuminate three critical points regarding US sex research before the publication of the Male volume. First, both men considered the observation of live sex to be part of scientific sex research, the “clinical demonstration” to which Dickinson referred in his title. It is clear also that Kinsey’s informal network of collaborators, whom he and his team referred to as “friends of the research,” included individuals who were willing to have sex with each other voluntarily under observation. Thus the dimensions of what kinds of data could be included in sex research, even clandestinely, were growing larger. Observation of animal sexual behavior could be published openly in the 1950s, but due to contemporary moral standards, similar human data could not. The twentieth-century sex researchers who observed live intercourse were rare and largely shunned by their professional peer groups, and Kinsey never admitted publicly to observing live sex.

Second, the texts and drawings highlight a forthcoming change in the technology used for sex research. While Dickinson favored pencil and paper, along with a typewriter, Kinsey would take a step further in the early 1950s, when he hired a professional filmmaker and photographer to capture sexual encounters that he arranged (and in which he sometimes participated) in his attic. (The publication of Wardell B. Pomeroy’s 1971 biography of Kinsey was the first public mention of the fact that sex acts were filmed in Kinsey’s home.) Although observing encounters in person made noting techniques and reactions in the moment possible, reviewing a film allowed for close-ups, repeated viewings, and comparison of different encounters over time. Dickinson’s texts and drawings communicate his immediate responses with phrases like “Not as clumsy as here shown, their motion too swiftly changing for representation.” However, that same phrasing points to the advantages of film, which could capture all motion.

Third and last, these texts and drawings demonstrate a unique kind of cooperation and collaboration between different generations of sex researchers. Kinsey’s first communication with Dickinson had been in October 1933 to thank him for a description of coitus interruptus as a contraceptive method, and from that letter sprang their multi-year knowledge exchange and collaboration. Kinsey—who was forty-three at the time of the encounters, while Dickinson was eighty-three or eighty-four—provided Dickinson with an opportunity to see heterosexual intercourse in a way that he had not had before. By doing so, Kinsey both honored his elderly mentor by arranging the encounters, and proved that he saw and thought about sex and sex research differently than Dickinson had imagined. The generational torch of sex research not only passed from the older man to the younger one, but also from the younger to the older, as new experiences and views of human sexual behavior expanded on those that came before.

The author thanks Jessica Murphy and Stephanie Krauss at the Center for the History of Medicine at Countway Library, Harvard University for their assistance, and the Center itself for permission to reprint excerpts from the text and the images. A grant from the New England Research Fellowship Consortium supported the author’s research.

Donna J. Drucker is Assistant Director of the Office of Scholarship and Research Development at the Columbia University School of Nursing. She is the author of The Machines of Sex Research, The Classification of Sex, Contraception, and Fertility Technology. She tweets from @histofsex

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com