A recent post by regular blogger Nikki Daniels (‘An open letter to bearded hipsters’) that has made the usual rounds of facebook and twitter has got me thinking about how male fashion has long been central to the way we define what it means to be a ‘real’ man. The blogger wrote about how, in 2014, the disturbing trend of ‘hipsters’ sporting beards left her unable to be sure of her sexual attractions. ‘You’re confusing me’, she exclaims. ‘…who is the real man and who is the poseur?’ [emphasis added] She paints a portrait of emasculated men, wearing beards but not doing the things men were designed to do (‘kill stuff…chase stuff…fuck stuff’). She denigrates the pretentious bearded hipster largely with the weapon of sexuality: the men’s potential queerness, and the withdrawal of her (and other women’s) sexual attraction. The homophobic, gender-queer phobic and misandrist tone of the widely-shared post unsurprisingly attracted much criticism. But the vitriol about the ‘pussies’ who dare to wear manly-looking beards, but who are actually ‘vegan nancy boys’ who used ‘products’ to groom them, was viewed over half a million times, and shared 10,000 times, including by some of my female friends. I don’t necessarily mean to give a bilious blogger more of a platform, but it bears thinking about–you guessed it–historically.

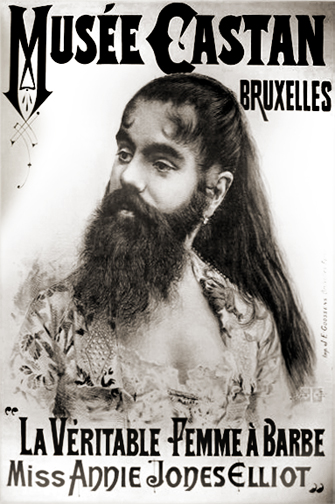

The way individual men or groups of men have chosen to dress or style their facial hair has long been one of the ways that the boundaries of the masculine ideal (also known as the ‘real man’) have been policed. Beards are of course one major talking point–not least because the ability or inability to grow a beard is and has been a marker of gender or the disruption of it, for men and for women. And of course having a beard or not having a beard could be a drastically different marker of masculinity in different times and places, and many times, as now, the meaning of beardedness could be confusing and hotly debated.

There are many other ways that men’s fashions have inspired confusion, vitriol and anger from onlookers—especially when hypermasculine or affluent fashions are co-opted by ‘unmanly’ men. Unsurprisingly, queer men have been the primary target here. As my co-editor Justin Bengry’s work on queer consumer culture demonstrates, there is also a long history of worrying over how to recognize queer and unmanly men by their fashion. In 1902, for instance, one fashion editor was keen to distance his publication from male readers who ‘wear corsets and spend the morning in Bond Street getting their hair curled’. He wanted there to be no confusion, so to speak.

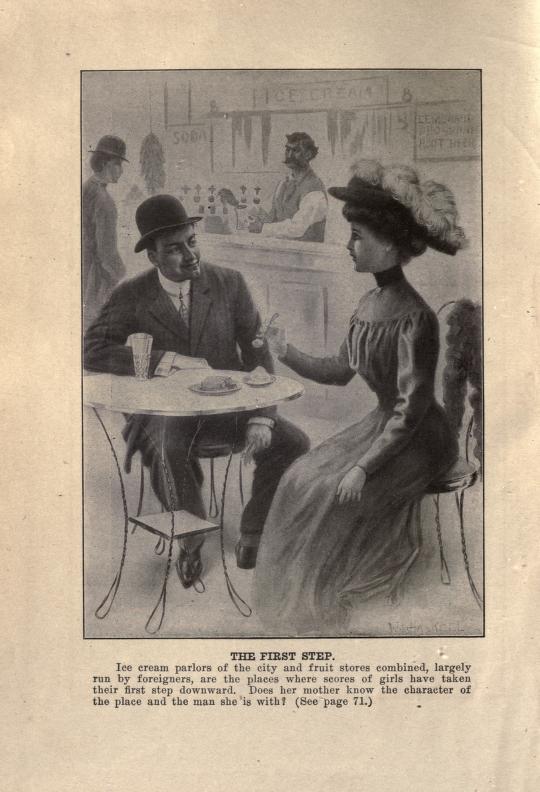

Ostensibly straight men have also been subject to attacks on their masculinity in which fashion has played a central role. My new research looks in part at masculinity and the image of the pimp in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. These men were widely despised for a number of reasons, but it was their effeminacy that was particularly offensive. This was articulated in large part through reference to the way in which they dressed. Pimps, as they were described, tended to dress in finery, at the extreme and unsubtle height of fashion, ridiculous both in its ostentation but also because these men dressed so far above their class. They were confusing: it is not surprising that ‘ponce’ was synonymous with pimp in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

These invectives were not just directed against men ‘beyond the pale’, however. In Marcus Collins’s work on the ‘new pornographers’ (the men who launched the softcore porn mags of the 1960s), he identifies an image of a ‘new man’ propagated by these magazines, one who cared about fashion and dressed well. However, it wasn’t long before this new man of the sexual revolution and his counterpart–the sexually desiring and available woman–broke down into diatribes about emasculation: real men didn’t care about their hair, nor did they care about women’s desires.[1]

A similar invective was launched against new models of masculinity that emerged in the 1990s. These figures, such as the ‘new man’, the ‘metrosexual’, and other manifestations of confusing ‘emasculinity’ (if you will) are beginning, in the work of Frank Mort and others, to be historicized. Hipsterism is just the latest target. There are many ways, of course, that hipster subculture can be hypermasculine. But within these frameworks hipsterism also gender-bends–the man in the picture in the linked ‘open letter’ blog is conspicuously wearing pink sunglasses. And meggings? Gay men wearing tight leggings might be accepted as a sign of a liberated subculture and tolerant society. But straight men wearing tight leggings: clearly a sign of the apocalypse.

As historian Lesley Hall wrote in her book Hidden Anxieties: Male Sexuality, 1900-1950, looking at male sexuality in the past can launch an immense challenge to the idea of the ‘the monolithic, unchanging, unproblematic… “normal” male’ by showing us not only how male sexuality has been a complicated experience for actual men in the past, but also how ideals of masculinity have changed profoundly over time. The relationship of beards, beard maintenance, and manliness in particular times and places has made for some excellent case studies and popular histories that link beards not only to masculinity, but also to race, age, and class.

Men–and their fashion sense– have been frequently held up to a patriarchal standard of gender and sexuality from which history appears unwilling to release them and whose borders are always carefully policed. What this recent anti-hipster blog shows is that women have also participated in this policing, at times using their desire (or the threat of the removal of their desire) to keep straight men on a straight path of simplified and unconfusing masculinity.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British and gender history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British and gender history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Very interesting, Julia! You might be interested in Alun Withey’s various posts on the history of beards and shaving too: http://dralun.wordpress.com/tag/beards/

Ah brilliant, thanks for that link! It will be really useful for our next Beard Week! post on Thursday as well.

Great post! And for the recent stuff: there’s Conchita Wurst (‘a bearded woman’) representing Austria at the Eurovision this year. 🙂 http://www.conchitawurst.com/

How excellent! Eurovision just got even more fascinating…

Pingback: The Erotics of Shaving in Victorian Britain | Notches: (re)marks on the history of sexuality

And for more recent furor over beards and gender expression see this article on men shaving off their beards in opposition to Conchita Wurst’s recent win at Eurovision:

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/conchita-wurst-russians-shave-off-beards-protest-over-eurovision-song-winner-1448196

Pingback: Hirsute Phoenix: Conchita Wurst, Beards, and the Politics of Sexuality | Notches: (re)marks on the history of sexuality

Pingback: The Erotics of Shaving in Victorian Britain – It's A Guy!