I’ve often said that researching prostitution makes me more of a labour historian than a historian of sexuality. Despite having typically been lumped into the same categories as homosexuality and other perceived sexual deviances, women who sold sex in the past connected their actions not to their sexuality but to their work.

They also very often saw themselves as a group of workers. We have evidence of collective identities and labour association amongst prostitutes in the nineteenth century: dozens of women marching through the streets of Aldershot banging pots and pans to protest brothel closures makes for just one striking example. By the 1950s, the organization of some prostitutes in London amounted to what one sociologist, Rosalind Wilkinson, called ‘trade union status’. This early sociological research revealed the beginnings of what was to become a powerful sex workers’ rights movement. By the 1970s, prostitutes in France, the United States, and Great Britain (to name a few) were organizing and leading protests for protection and for labour rights.

By the twenty first century, many women who sell sex choose to call what they do ‘sex work’ and to call themselves ‘sex workers’. This can have different meanings for different women. For some, acknowledges their work as normal, necessary, and as something to be respected. For others, it serves to divorce their sexual labour from their own sexualities. Still others use it to insist that sex work be considered alongside all other work: work that can be both exploited or not exploited, chosen or not chosen.

As a historian, I use the terms ‘sexual labour’ and ‘women who sold sex’ to avoid anachronism, but I still explicitly recognize that for most women who sold sex in the past, prostitution was a job. It must be analysed as a history of labour every bit as much as a history of sexuality. Indeed, if we want to think about prostitution in terms of the history of sexuality, we should be looking far more at the men who buy sex rather than the women who sell it. So far, there is a shocking paucity of historical (or present-day) studies on this enormous group of people who participate in commercial sex.

As a historian and a feminist, I am well aware of the battles that rage around the term ‘sex work’. Some feminists insist on using the term ‘prostituted woman’, implying that no woman can or would choose to sell sex. Indeed, one of the most oft cited ‘facts’ thrown at me by students and laypersons when they encounter my research on prostitution as women’s labour is that ‘no little girl says she want to be a prostitute when they grow up.’ Putting aside all the other arguments against this claim, no little girl says she wants to clean toilets when she grows up, either.

The world, then as now, is turned by people who have not positively chosen their jobs. Women who sold sex in the past did so as a reaction to other poorly paid, arduous, demeaning, and exploitative labour choices and because of a crucial lack of social support. Several late nineteenth-century studies found that up to half of the women selling sex in Britain had been domestic servants, and that many had hated it so much they had willingly left service. ‘What will you give me if I do give this up’, one prostitute asked a woman police constable in the 1920s, ‘a job in a laundry at two pounds a week–when I can make twenty easily?’ ‘I’d rather die than go into domestic service’, another told the journalist Mary Chesterton in 1935.

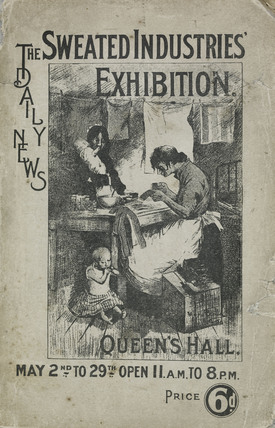

The difficult truth is that testimonies of historical as well as present-day prostitutes provides ample evidence that women do choose sexual labour in the face of dire economic circumstances and terrible labour alternatives. Perhaps this is why we find it so difficult to imagine prostitution as work, and to take the organization of sex workers seriously. It involves a recognition that sex work is deeply connected to the exploitative capitalist economy of which we are all a part. As George Bernard Shaw wrote in 1912, at the height of the campaign against the commercial sexual exploitation of girls or ‘white slavery’:

The wages of prostitution are stitched into your button-holes and your blouse, pasted into your match boxes and your boxes of pins, stuffed into your mattresses, mixed with the paint on your walls, and stuck between the joints of your water-pipes. The very glaze on your basin and tea-cup has in it the lead poison that you offer to the decent woman as a reward for honest labour.

If anything, Shaw’s words ring more true today, in light of our increasingly iniquitous global economy, where cheap domestic, agricultural and industrial labour and poorly regulated manufacturing are seen as crucial to satisfying the ever growing demands of affluence and comfortable living.

And so, on this international workers’ day, I suggest that we should think about the way that sexual labour is connected to the unpaid, underpaid, and exploited work that women–and to a much lesser, but still important extent, men–perform in order to sustain the global capitalist economy. And instead of trying to divorce prostitution from work, we should think instead about the ways that our own demand for licit goods and services is entangled with the illicit and sexual economy, and the ways in which we are complicit in the much wider exploitation of labour.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British and gender history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British and gender history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Excellent article and wholly respect the points made; I would be interested to know how the author would consider Radin’s work (Cotested Commodities, 1996) and the question whether sex ought to be a commodity? Whether, within the context of capitalist inequality sex work actually hinders gender / labour equality, and whether sex work perpetuates the history of men’s (patriarchal) rights over female bodies (Shrage raises this point in a similar idebate)? I realise these are perhaps ethical questions and not necessarily suitable for this forum but they’re questions that I find challenging on this subject. Fascinating reading!

Pingback: But What about Trafficking? | Border Criminologies

Pingback: Aber was ist mit Menschenhandel? | menschenhandel heute