Part 2: The Case of the Vanishing Queen

Regular readers may well be poised on the edge of their seats, awaiting the resolution of Tuesday’s nail-biting cliffhanger. When last we saw our middlebrow heroes, gruff butch, Marion Bradford, had met a grisly end at the bottom of a precipice. Her fainting femme, Roberta Symes, having recovered her senses, was set to embark on the path to heterosexuality. Such is the fate of lesbians in Mary Stewart’s post-war fiction. But how do gay men fare? Join us, gentle reader, as we reach our exciting climax.

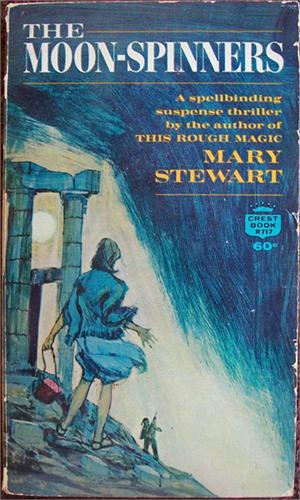

Whereas Roberta and Marion were caught up in the drama against their will in Wildfire at Midnight (1956), in The Moonspinners (1962) male homosexuality is inextricably bound up with criminal wrongdoing. Set in the Cretan countryside, this novel follows Nicola Ferris as she becomes embroiled in a tricky game of cat and mouse with hotel owners, jewel thieves, and general ne’er-do-wells, Stratos and Tony. When we first encounter Tony we are unaware of his criminality. However, his status as an outsider is signposted nonetheless. As was the case in Wildfire at Midnight, queer readers shouldn’t take long to spot the markers of campness and effeminacy. Tony’s speech is theatrical, his inflections and over-familiar endearments standing out (not to mention his interest in interior design),

Oh my dear, a little, only a little, and ghastly Greek at that, I do assure you. I mean, one gathers it works, but I never speak it unless I have to. Luckily Stratos’ English is quite shatteringly good… Here we are. Primitive, but rather nice, don’t you think? The décor was my own idea. (p. 119)

He is also preened and polished, with ‘close-fitting and very well-tailored jeans’, and hair that is ‘fairish, fine and straight, rather too long, but impeccably brushed.’ (p. 114) His movements bear an unmistakable femininity: ‘ “Cheerio for now,” said Toby amiably. His slight figure skated gracefully away down the stairway.’ (p. 123)

Stratos, on the other hand, has nothing to immediately mark him out as deviant. He inhabits a stereotypical Greek masculinity of physical strength and power, and booming conviviality mixed with a short temper. In fact, the only signpost to Stratos’s potential deviance is his association with Tony. We learn that they ran a successful restaurant together in London and have recently arrived in Stratos’s home village of Agios Georgios, ostensibly to turn the local kafenéion into a hotel, but in reality to escape the heat from a soured criminal venture. We later learn that their relationship has also soured and that Tony plans to cut his losses when the heat cools.

Homosexuality remains unnamed but there for the reader to discern. Nicola’s travelling companion, Frances, makes a throwaway comment about Tony’s reasons for being in Agios Georgios,

Hm. He looks a pretty urban type to settle here, even for a short spell… unless the beaux yeux of the owner have got something to do with it. He came with him from London, didn’t he? (p. 156)

Here, as in the case of the lesbian relationship in Wildfire at Midnight, the use of the French expression (‘beautiful eyes’) thinly cloaks the implication of homosexuality, protecting the more fragile reader (and excluding the less ‘sophisticated’). Similarly, when Nicola rescues Colin, a teenager taken hostage by the crooks, he tries to describe Tony’s way of speaking only for Nicola to cut him off,

‘I remember exactly what he said. […] “I’ll take my cut here and now, and don’t pretend you’ll not be glad to see the last of me, Stratos, dear.” That was the way he talked, in a kind of silly voice; I can’t quite describe it’.

‘Don’t bother, I’ve heard it. What did Stratos say?’ (p. 222)

Again, the explicit accusation of homosexuality is obscured, but there for the informed reader to infer. The implication here is that Tony’s camp manner and, by extension, his homosexuality, are not suitable topics for a teenage boy. Considering that this book involves murder, kidnapping, extortion and drug smuggling, all of which Colin is witness to, one might wonder what new evils the mere naming of homosexuality might bring to proceedings.

At the book’s denouement, Stratos is brought to rights but Tony has gracefully absconded, balletically leaping over Frances into a getaway craique, with a camply flippant farewell: ‘ “Excuse me dear –” […] “…High time to leave.” I thought I heard the light, affected voice quite plainly. “Such a rough party…”’ (p. 332-3). Here ‘true’ male homosexuality (the effeminate and affected) is slippery, unsolvable and uncontainable, as Tony sails off to camp it up anew on a distant shore. In Stewart’s world endings are safe places where good triumphs over evil, the guy gets the girl, and everyone relaxes over a jolly hard-earned Campari and soda. In such a world Tony’s escape niggles, troubling middlebrow conventions of narrative resolutions. Tony evades justice, and as a result male homosexuality is at large, turning up next who knows where, to infiltrate and disrupt the respectable and the morally upstanding.

In Stewart’s world homosexuality in any form brings a touch of exoticism and sophistication to proceedings, and rewards the urbane reader with an opportunity to feel part of a knowledgeable and worldly in-crowd. But the in-joke is ultimately on any character who dares to tread a non-normative path. Lesbians are plot fodder, sacrificed for a quickly turned page. Gay men are more insidious, at the heart of dirty dealings. Tony may escape but in a sense he is the one character to be fully exorcised. For Marion death is final; for Roberta a new life beckons; for Stratos the wheels of conventional justice give him a neatly packaged future beyond the final page. But in going beyond the liminal spaces, Tony sails off the edge of Stewart’s map. Here be dragons? Or worse – here be homos?

Amy Tooth Murphy is an oral historian specialising in lesbian and queer oral histories and post-war lesbian history, with an emphasis on domesticity. Amy completed her PhD, ‘Reading the Lives between the Lines: Lesbian Oral History and Literature in Post-War Britain’, at the University of Glasgow in 2012. She is currently based at the University of East London where she is Project Manager for the Bethnal Green Memorial Project.

Amy Tooth Murphy is an oral historian specialising in lesbian and queer oral histories and post-war lesbian history, with an emphasis on domesticity. Amy completed her PhD, ‘Reading the Lives between the Lines: Lesbian Oral History and Literature in Post-War Britain’, at the University of Glasgow in 2012. She is currently based at the University of East London where she is Project Manager for the Bethnal Green Memorial Project.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great essay, Amy!