Russian history of sexuality is very problematic. We have yet a lot to discover about same-sex relationships, sexual variations and attitudes to various sexual practices on the Russian pathway to modernity. The little we know suggests that one’s sexual identity was subject to close scrutiny from the community, the church and the state in the early modern period: same-sex relationships were harshly prosecuted, heteronormativity enforced. However, intersex people or, historically, ‘hermaphrodites’ (dvuudye or muzhesheny in Russian) represented a true puzzle for the authorities and local community.

In 1732 the residents of Mikhailovo, Tula district, learnt that a local blacksmith Ivan Karpov, a respected community member, married but with no kids, was, in fact, a woman. They learned this from the statement given by a passing soldier who knew him as a woman called Marina. It came as a shock to his wife, Praskov’ia, who insisted that they lived together as a man and a wife, that is, had sexual intercourse. Apparently, Ivan had a penis (muzskoi ud – male genital) originating ‘temporarily’ (as it was pointed out in the court protocol) from the vagina (zhenskii ud – female genital). Praskov’ia also insisted that Ivan took her virginity. She never suspected that her husband was a ‘disgusting woman’ (merzkaia baba), probably because during their washing in the bathhouse, Ivan made sure Praskov’ia could not see his genitals properly (he hid behind birch twigs). For this transgression without authorities’ permission, Ivan (or Marina as he was called in the records) was locked in a specially built pillar, chained to the wall, and put on display by the local bishop, Veniamin, a highly educated priest ambitious in his civilising mission.

The story of Ivan/Marina generated acute interest from the royal court and Empress Anna Ivanovna demanded that the double-sexed woman (dvuudana baba) be sent to her quarters immediately. The bishop Veniamin, however, was not keen on losing his living exhibit, and deterrence tool for the local community, and did everything to delay the process. When Ivan was released from the pillar, he was deaf and mad from the horror of being locked in his prison alive. He was finally imprisoned in the monastery for life.

This might be appear only an outstanding case if not for a further example ten years later. In 1743 another ‘double-sexed person’ was arrested and held by the St. Petersburg police. This time, it was a palace servant Ivan Antonov, who called himself Natalia and who had ‘female genitals in addition to male genitals’. The police asked the Synod to provide information from both ecclesiastical law and active statutes as to what to do with him, because ‘having two natures he cannot stay among people without temptation’.

The Synod stated clearly that there were no exact ecclesiastical laws on the matter and ordered the police,

to take precautions for him not to mess up with both sexes, that is, to make him give a written obligation to choose the sex he is more inclined to according to his nature and if, at any later time, he converts to the other, to punish him by death. It shall be his parish priest’s responsibility to look after him cautiously and check upon him regularly.

The decision in the latter case reveals the anxieties about ‘dubious’ sexuality of hermaphrodites. Pierre Darmon points out that while these cases manifest a refusal of hermaphrodites’ monstrous nature, they nonetheless apply a more dangerous concept of moralizing and ascribing to social and moral order. Indeed, doubts about someone’s sex not only involved that person, but the entire community surrounding that person: family, peers, lovers or spouses, colleagues etc. Doubts about sex, then, became a moral problem rather than a physical question, affecting many others and also morality in general. The danger of an inconclusive, ambiguous sex was controlled not by disclosure and (re)assignment, but by containment. The rationale of sex was primarily achieved by its being inscribed in the social, economic, moral and ultimately legal fabric of the community.

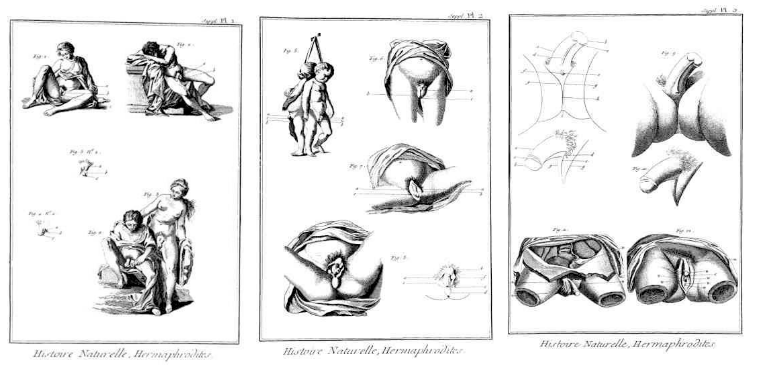

At the same time, scholars including natural scientists and medical professionals, became fascinated by hermaphrodites’ ‘two natures’ and tried to provide plausible explanations for them. Russian scientists debated the difference between real hermaphroditism and simple genital deformity. In the 1760s and 1770s, hermaphroditism also became central in discussions on preformism and epigenesis. Kaspar Friedrich Wolff (1735-1794), developing his epigenetic theory, explained hermaphroditism as a possible variation of development rather than God’s punishment.

Many such discussions took place in the Russian Academy of Sciences, which maintained its own collection of hermaphrodites. Peter I initiated this interest by founding the Kunstkamera (the cabinet of curiosities). He was especially interested in human generation and issued numerous ordinances prohibiting the killing of deformed children and animals, ordering the provincial chancelleries instead to send them to St. Petersburg. For a living human with defect Peter was willing to pay 100 roubles, but for the dead – only 15.

Iakov, another blacksmith, was one of Peter’s ‘living exhibits’. He was a hermaphrodite and he lived and worked at the Kunstkamera where he showed his ‘deformities’ to spectators. Upon his death in 1737 Iakov was autopsied, and his body and organs were preserved in the Kunstkamera for further study. By the 1740s, six hermaphrodites lived and worked in Kunstkamera being both living exhibits and experimental material.

In eighteenth-century Russia, hermaphrodites reveal ambivalent attitudes to sexuality and sexual identity in the context of Enlightenment policies, advances in science and state’s attempts to create an orderly society. They were expected to conform to their ascribed gender and maintain heterosexual behavior, contributing to heteromormativity. However, their biology did not matter in choosing or ascribing their gender, and thus their heteronormative contract was more important than their bodies or personal identities.

Marianna Muravyeva is a professor and Marie Curie senior research fellow at Oxford Brookes University. She specializes in histories of crime, law, gender and the history of sexuality in early modern Europe. She is editor of Gender in Late Medieval & Early Modern Europe (2013) and Shame, Blame, & Culpability: Crime and Violence in the Modern State (2012). She tweets from @MMuravyeva

Marianna Muravyeva is a professor and Marie Curie senior research fellow at Oxford Brookes University. She specializes in histories of crime, law, gender and the history of sexuality in early modern Europe. She is editor of Gender in Late Medieval & Early Modern Europe (2013) and Shame, Blame, & Culpability: Crime and Violence in the Modern State (2012). She tweets from @MMuravyeva

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on What the Trinkets Told Me and commented:

A quite fascinating post about the social problems presented by intersex people in early modern Russia.

Pingback: 'A Temporary Member': 'Hermaphrodites' and Sexu...

Reblogged this on HITT – Hanse Inter Trans* Tagung and commented:

“Ein temporäres Mitglied”: “Hermaphroditen” und die sexuelle Identität in Russland des 18. Jahrhunderts von Marianne Muravyeva. Ein Artikel über den Umgang der russischen Justiz und Medizin mit ihren intersexuellen Bürgern.

Pingback: ‘Paddy Petticoat’, a nineteenth-century Irish ‘hermaphrodite’ criminal. Part iii: The label | Elaine Farrell