What does a mock-sodomized chicken on a theater stage in 1959 in Tokyo have to do with gay prison sex in World War II France? Quite a lot, as it turns out, if the performer in Tokyo is the founder of the dance art Butoh, Hijikata Tatsumi, and the French prisoner is Jean Genet, who soon afterwards went on to transform his escapades into novels. Both were connected (if not in person) through artistic networks and discourses that spanned cultural centers from Tokyo to Paris and New York.

Butoh is a radical performance art that emerged from the cultural ferment of late 1950s Tokyo. It is notoriously difficult to define as it has been continually evolving since its first inception, but two of its trademarks are its use of ultra-slow and “unnatural” movements and expressions and its obsession with the darker side of the human experience. I was originally drawn to Butoh history thanks to a student who researches the contacts between early Butoh artists and exponents of German expressionist dance (Neuer Tanz) such as Mary Wigman and Harald Kreutzberg. While doing some background reading, I was surprised to find out that Hijikata’s first Butoh performance in May 1959, called kinjiki 禁色 (Forbidden Colors), had a disturbing sexual theme. Here is the gist of the performance:

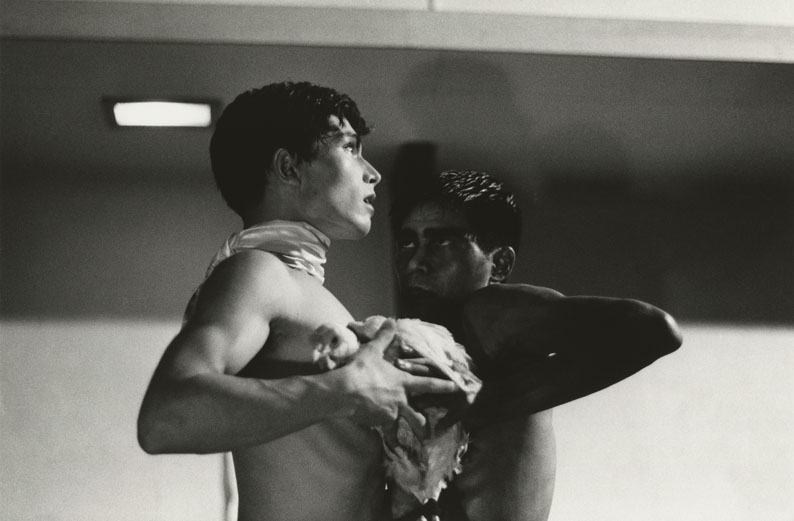

In this piece, a young man (Yoshito Ono) has sexual relations with a hen, after which another man (Tatsumi Hijikata) makes advances to him. There is no music. The images are striking: the young man smothers the animal between his thighs to symbolize the act. (Viala and Masson-Sekine)

The contemporary Japanese art world was shocked. But Hijikata would not let that distract him from further probing the dark possibilities of this newborn dance form, which he aptly termed ankoku butō (dance of darkness). He integrated sexual elements into other performances in the years to come, such as his October 1968 performance Hijikata Tatsumi and the Japanese: Rebellion of the Body, in which he entered the theater with a golden phallus and paraded it around the stage.

From where did Hijikata pull his raw sexual imagery and his obsession with the dark sides of the human body? I already mentioned the indirect influence of Mary Wigman’s expressionist dance. She explored darkness, death and the occult and their relationship to gender norms in many of her performances, such as Hexentanz (Witches’ Dance), and it is not hard to imagine how these themes and the underlying bodily significations might have traveled with Japanese artists such as Eguchi Takaya who came in contact with German expressionism through personal experience or contact with Wigman’s students.

There were more immediate influences on Forbidden Colors too. Hijikata had borrowed the title from Mishima Yukio, then already an influential writer and no stranger to confronting homosexuality in his own works, famously in his semi-autobiographical Confessions of a Mask (1949), but also in Forbidden Colors (1954). In the title of both novel and performance the character for “color” 色 carried over the meaning of lust or eros from the Early Modern period (1600-1868), as in nanshoku 男色, the codified sexual relationship between an older, dominant man and a younger, submissive boy. This theme was not very salient in Mishima’s book but featured prominently in Hijikata’s and Ohno’s performance.

Butoh critics have shown that in spite of the title, the manner in which kinjiki presented homosexuality was inspired less by Mishima than by French novelists. It is well known that Hijikata read everything from de Sade to Sartre and absorbed surrealist and existentialist thought. Jean Genet in particular, with his refusal of the dominant sexual morality of the time and a strong interest in the abject, filthy side of the body, seemed to have shared – or inspired – Hijikata’s outlook.

At one point in the performance, when Hijikata forces himself on Ohno, he cries “Je t’aime”. In her engaging analysis on the role of cross-dressing in Hijikata’s dance, Catherine Curtin recently suggested that the French phrase should be read as Hijikata’s attempt to “open up a space for the possibilities of male-male desire, which had been denied within his own culture” (p. 475). That strikes me as inaccurate, and not just because I feel that Hijikata turned to sexuality more as a means to push the limits of artistic (self-)expression or maybe even to tap into the existential knowledge of the body than to stage political interventions.

More importantly, the juxtaposition of Hijikata’s alleged “own culture” and a somehow “French” take on sexuality coming from the outside is problematic. Given the various currents that breathed life into butoh, the French exclamation appears to function in quite the opposite way: as a signifier invoking – or inviting the audience into – a shared understanding of the aesthetic uses of sexuality, and in a wider sense, the transnational cultural space they co-inhabited with Hijikata, Mishima, Genet, Wigman and other producers and consumers of avant-garde art around the globe.

Michael Facius is a Research Fellow at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of History, Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on Japan and East Asia in global history. In his current project, which is part of a Collaborative Research Center on the premodern history of knowledge on the pre-modern history of knowledge called “Episteme in motion”, he explores evolving views of the Early Modern period in twenteith-century Japan.

Michael Facius is a Research Fellow at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of History, Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on Japan and East Asia in global history. In his current project, which is part of a Collaborative Research Center on the premodern history of knowledge on the pre-modern history of knowledge called “Episteme in motion”, he explores evolving views of the Early Modern period in twenteith-century Japan.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: The Origins of Japanese Butoh Dance – The Room Installation